“Community maxxing in the form of screenless hangs at dance parties, dinners, etc., will become the new ‘clean’ aesthetic as a direct response to surveillance and the influencer economy taking over public spaces. Performative offline is the new performative online.” When writer Jenny Deluxe made this prediction for culture magazine SSENSE, she articulated something millions of people had been feeling but couldn’t quite name. The era of broadcasting every moment of your life to algorithmic feeds is ending. What’s replacing it isn’t a simple retreat from technology, but something more interesting: a collective renegotiation of how we relate to digital platforms, our data, and each other.

The phrase “performative offline” sounds cynical at first, as if the impulse to step back from constant posting is just another form of image management. But Deluxe imagined something more deliberate: refusing to be tracked, refusing to be known, refusing to let our nervous systems get hijacked, refusing to give everything up to AI, and refusing to succumb to how social media has become a stand-in for reality. This isn’t about temporary digital detoxes. It’s about a fundamental reassessment of what we owe the platforms that have colonized our attention.

The Trust Shift

Something quietly changed in how people think about their online presence. For over a decade, the dominant model was broadcast: create content for massive platforms, hope the algorithm favors you, measure success in followers and engagement metrics. The platforms encouraged this by designing features around public posting, viral sharing, and quantified popularity. Being online meant being visible to everyone.

By 2026, that model has started to feel dangerous. Users have watched their content become training data for AI systems. They’ve seen their personal information harvested and sold, their attention auctioned to advertisers, their emotional responses engineered by engagement-maximizing algorithms. The platforms that promised connection delivered surveillance. The communities that promised belonging delivered comparison and anxiety.

The response has been a migration toward smaller, more controlled spaces. Discord servers, private group chats, gated newsletters, invite-only communities. These spaces offer something the broadcast model can’t: trust. When you know who’s in the room, you can speak differently. When you’re not performing for an algorithm, you can be authentic. When your words won’t be scraped for AI training, you can think out loud without worrying about future consequences.

This isn’t a rejection of digital connection. It’s a reformation. People still want to share, discuss, and connect online. They just want to do it in spaces they control, with people they’ve chosen, under terms they’ve consented to. The mass platforms remain, but they’re increasingly treated as public utilities rather than intimate communities, places you use strategically rather than live in.

Micro-Communities Rising

The numbers tell a story of migration. While major social platforms report stagnant or declining daily active usage among key demographics, platforms designed for smaller communities are thriving. Discord has grown from a gaming chat app to a general-purpose community platform with millions of servers covering every conceivable interest. Newsletter platforms like Substack and Beehiiv have enabled creators to build direct relationships with audiences, bypassing algorithmic gatekeepers. Private communities on Geneva, Circle, and other purpose-built platforms have proliferated.

What distinguishes these spaces from traditional social media isn’t just their size but their structure. Mass platforms are designed to maximize engagement through algorithmic feeds that surface whatever content will keep you scrolling. The relationship is between individual and platform, with other users as content sources rather than genuine connections. Micro-communities are designed around actual relationships. The owner or moderator sets the terms. The members know each other, at least by handle and reputation. The conversation develops over time among familiar participants.

This structural difference produces different behaviors. In broadcast environments, people optimize for reach and reaction. Posts become performances. Controversial takes generate engagement, so the incentive is toward provocation. In community environments, people optimize for reputation and relationship. Thoughtful contributions build standing. Trolling gets you excluded. The incentives align with the behaviors most people actually want.

Media creators who understand this shift have gained significant advantages. A newsletter with 10,000 engaged subscribers who open every email, click links, and reply to questions is more valuable than 100,000 passive social media followers who scroll past without registering. A Discord server where fans actually discuss your work, recommend it to friends, and provide genuine feedback creates opportunities that viral posts cannot. The metric that matters isn’t reach but depth.

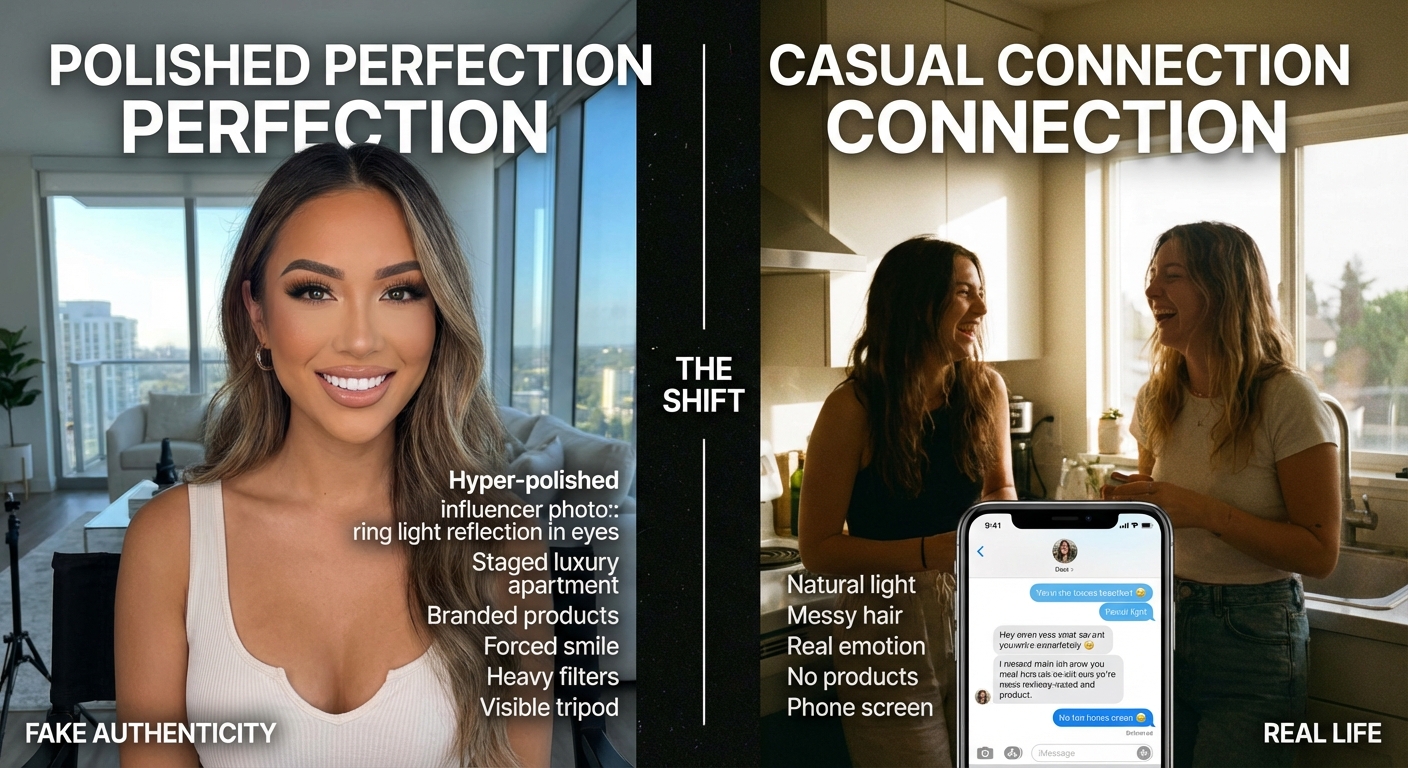

The Death of Influencer Culture

For a decade, the influencer economy seemed like the future of media and commerce. Individuals built personal brands, accumulated followers, and monetized their attention through sponsored content, affiliate links, and merchandise. Brands poured billions into influencer marketing. Young people listed “influencer” as a top career aspiration. The model appeared sustainable because it seemed to work for everyone: creators got paid, brands got exposure, audiences got content.

By 2026, the model has cracked. Audiences have developed sophisticated resistance to sponsored content, recognizing the markers of paid partnerships and discounting them accordingly. The over-polished aesthetic that once signaled aspirational lifestyle now signals inauthenticity. AI-generated content floods the platforms, making human authenticity simultaneously more valuable and harder to verify. As research on how AI affects our thinking has shown, technology shapes cognition in ways we’re only beginning to understand. Trust, the fundamental currency of influence, has become scarce precisely when it matters most.

The creators thriving in this environment are those who recognized the shift early and built genuine communities rather than audience numbers. They reply to DMs. They show up in comments. They share failures as well as successes. They treat their followers as participants rather than consumers. This approach doesn’t scale the way broadcast influence did, but it creates something more durable: actual relationships with actual people who care about what you’re doing.

Gen Z Rewrites the Rules

The generational dynamics of this shift are striking. Gen Z, the demographic that grew up entirely within social media, is leading the movement away from it. Not away from technology generally, but away from the specific model of public performance and algorithmic curation that defined the 2010s. They’re the first generation to understand intuitively that the platforms are not neutral tools but designed environments with interests that may not align with their users’.

This skepticism extends to work culture. Gen Z is openly questioning the “grind at all costs” mindset that earlier generations were sold. The definition of success is expanding beyond job titles and corner offices. Portfolio careers, where income comes from multiple sources rather than a single employer, are becoming normal rather than exceptional. “Soft quitting,” maintaining employment while refusing to go above and beyond for companies that don’t reciprocate loyalty, isn’t seen as laziness but as rational boundary-setting.

The connection between digital and work culture isn’t coincidental. Both represent younger generations refusing inherited frameworks that no longer serve them. If the implicit deal of the 2000s was “give your data to platforms and your best years to employers in exchange for connection and advancement,” Gen Z is recognizing that deal as broken and proposing new terms. They want careers that align with their values, offer real growth, and respect their boundaries. They want digital lives that don’t require constant performance, surveillance, or anxiety.

Recent research shows 56% of Gen Z workers would quit jobs that don’t support their ambitions, and over 50% have no interest in middle management. They’d rather grow as individual contributors, maintaining autonomy over their time and energy. Career minimalism, working with intention and protecting your energy, isn’t a failure of ambition but a redefinition of what ambition means.

Authenticity as Strategy

The word “authenticity” has been so overused in marketing contexts that it risks meaninglessness. Every brand claims to be authentic. Every influencer performs authenticity. But the 2026 version of authenticity is something harder to fake precisely because it requires not performing.

Authenticity in micro-communities means showing up consistently over time, so people can see who you actually are rather than who you’re pretending to be. It means admitting uncertainty and changing your mind when presented with better arguments. It means having interests that aren’t monetizable and relationships that aren’t leverageable. The algorithms can’t detect this kind of authenticity, which is partly the point. You can’t optimize for it because optimization is what it refuses.

For individuals navigating this landscape, the implications are practical. The social capital of the future isn’t followers but relationships. The media strategy that works isn’t viral hits but consistent presence in spaces that matter to you. The personal brand that resonates isn’t polished perfection but visible humanity. These shifts reward different skills: listening over broadcasting, depth over breadth, patience over urgency.

For organizations, the implications are equally significant. The brands succeeding in 2026 are those that participate genuinely in communities rather than trying to exploit them. They sponsor Discord servers rather than billboard ads. They hire community managers who actually participate rather than just moderate. They accept that authentic community presence can’t be scaled or automated because the whole point is that it’s human.

The Bigger Picture

The cultural shift of 2026 isn’t really about technology at all. It’s about what we want from our relationships, our work, and our lives. The platforms and tools we use are reflections of those deeper preferences, which are themselves shaped by economic conditions, generational experiences, and accumulated wisdom about what actually makes people happy.

The research on human wellbeing has been consistent for decades: strong relationships, meaningful work, and a sense of community matter more than status or wealth beyond a threshold. The digital platforms of the 2010s often undermined these sources of wellbeing even while promising to enhance them. Social media compared you to everyone and found you wanting. The attention economy fractured your focus and sold your concentration to advertisers. The gig economy offered flexibility while stripping security. The implicit bargain, that technology would make us more connected, productive, and successful, delivered something more ambiguous.

The 2026 renegotiation is an attempt to keep what technology does well while refusing what it does poorly. People still want global connection, instant communication, and access to information. They don’t want algorithmic manipulation, surveillance capitalism, or the pressure to perform their lives for unseen audiences. The micro-communities, the authenticity orientation, the boundary-setting in work and life are all expressions of the same underlying demand: a digital world that serves human flourishing rather than extracting from it.

Writer Jenny Deluxe introduced a word for this moment: “respair,” meaning the return of hope after a period of despair. After years of growing concern about technology’s effects on attention, relationships, and democracy, there’s something hopeful about millions of people quietly rebuilding digital life on more human terms. The cultural exhaustion of always being online has given way to something more constructive: active choices about how to engage. They’re not waiting for platforms to change or governments to regulate. They’re voting with their attention, migrating to spaces that respect them, and discovering that the alternative to algorithmic existence isn’t isolation but community.

The performative online era isn’t ending because people got tired of technology. It’s ending because people got tired of pretending. What comes next won’t be a return to some imagined pre-digital authenticity. It will be something new: digital tools used deliberately, relationships built carefully, attention protected fiercely. The year we stopped pretending to be online might also be the year we started actually being there.