A toddler drops a ball and watches it bounce. She pours water from a cup and sees it splash. She pushes a tower of blocks and observes it topple. Each of these experiences teaches her something about how the physical world works, rules she’ll internalize so deeply that she’ll never need to consciously remember learning them. By the time she can talk, she already knows that unsupported objects fall, that water flows downhill, that heavy things are harder to push than light ones. No one taught her Newton’s laws; she derived her own intuitive physics from observation.

Researchers in artificial intelligence have spent decades trying to give machines this same understanding, and for decades, they mostly failed. Traditional approaches involved programming explicit physical rules, essentially giving computers textbook physics. But this method proved brittle, unable to handle the messy complexity of real-world situations that depart from idealized models. More recent deep learning systems excelled at pattern recognition in static images but struggled with dynamic scenes, unable to predict what would happen next when objects collided or fluids flowed.

Now, a new approach called “world models” is showing remarkable promise. These systems learn physics the way the toddler does: by watching. Given millions of videos of objects moving through space, world models learn to predict what will happen next, not by applying explicit rules but by discovering patterns in the data. The implications extend far beyond academic curiosity. If AI can develop robust intuitive physics, it could revolutionize robotics, autonomous vehicles, video game design, and scientific simulation. Some researchers believe world models represent the most important frontier in AI development since the transformer architecture that powers systems like ChatGPT.

What World Models Actually Are

A world model is an AI system that maintains an internal representation of the physical world and uses that representation to predict future states. The concept isn’t new; cognitive scientists have long theorized that human brains build similar internal models to navigate reality. What’s new is that we now have the computational techniques to implement world models at scale, and the results are exceeding expectations.

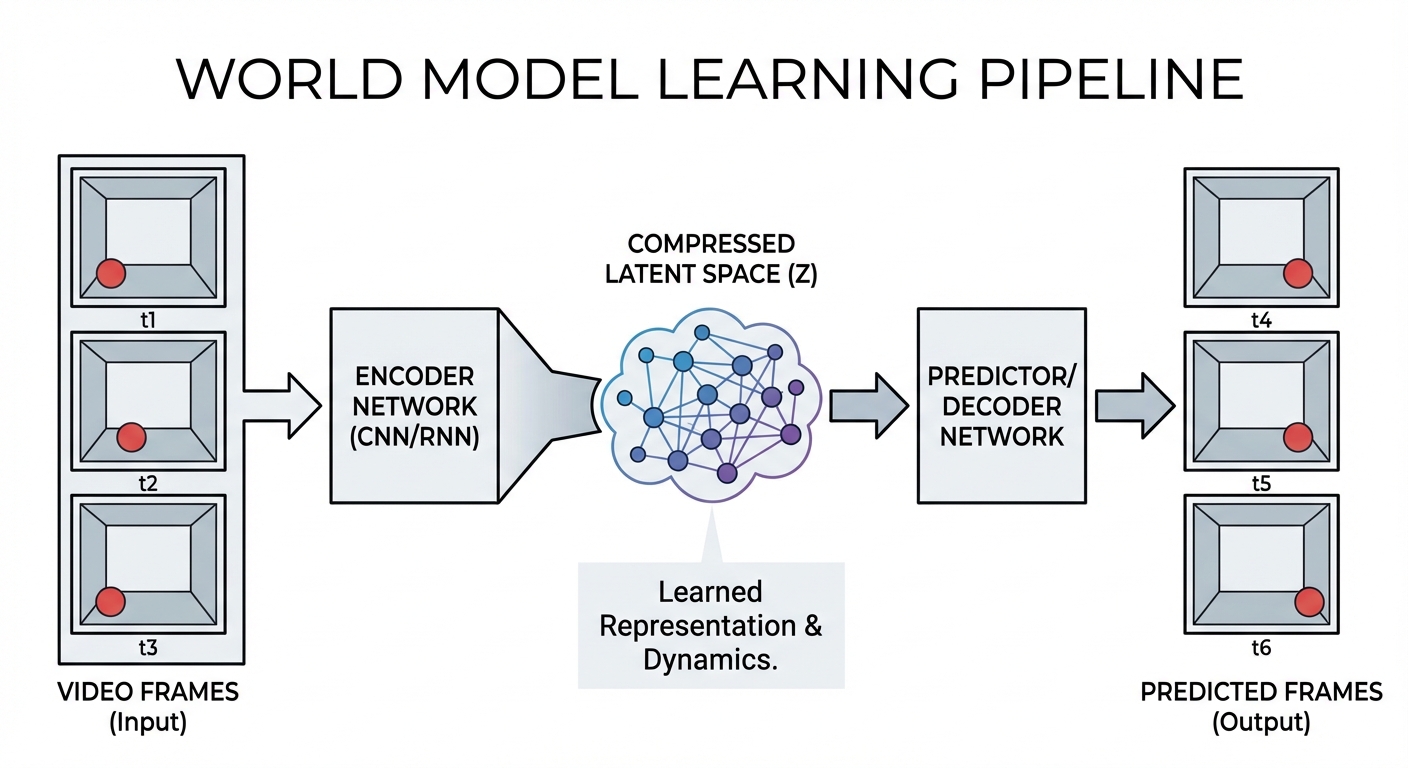

The technical foundations draw on several threads of machine learning research. Generative models, which learn to produce new data that resembles training data, provide the basic framework. Video prediction models, which try to forecast upcoming frames given previous ones, force systems to learn something about physical dynamics. Representation learning, which discovers useful ways to encode complex inputs, enables efficient internal modeling. World models combine these approaches, learning compressed representations of environments that support accurate prediction and planning.

Consider a simple example: predicting the trajectory of a thrown ball. A physics textbook would tell you to apply Newton’s laws, calculate the parabolic path accounting for gravity and air resistance, and determine where the ball will land. A world model approaches the problem differently. Having watched thousands of videos of thrown balls, it has learned patterns in how balls move through space. It doesn’t know the equations of motion; it knows that balls in this kind of situation tend to follow this kind of path. The prediction is implicit in learned associations rather than explicit in mathematical formulas.

This might sound like a less rigorous approach, and in some ways it is. A physics engine applying precise equations can calculate exact trajectories that world models can only approximate. But world models have compensating advantages. They handle uncertainty gracefully, understanding that predictions become less reliable further into the future. They generalize across situations, applying intuitions learned from balls to other thrown objects. Most importantly, they can learn about phenomena that resist mathematical formalization, including complex interactions, novel materials, and real-world messiness that physics simulations struggle to capture.

The Technical Breakthrough of 2025-2026

World models existed as a research concept for years before the recent explosion of interest. What changed was scale and capability. The same transformer architectures that revolutionized language AI turned out to work remarkably well for video prediction. Researchers discovered that training large models on massive video datasets produced emergent understanding of physics that simpler systems couldn’t achieve.

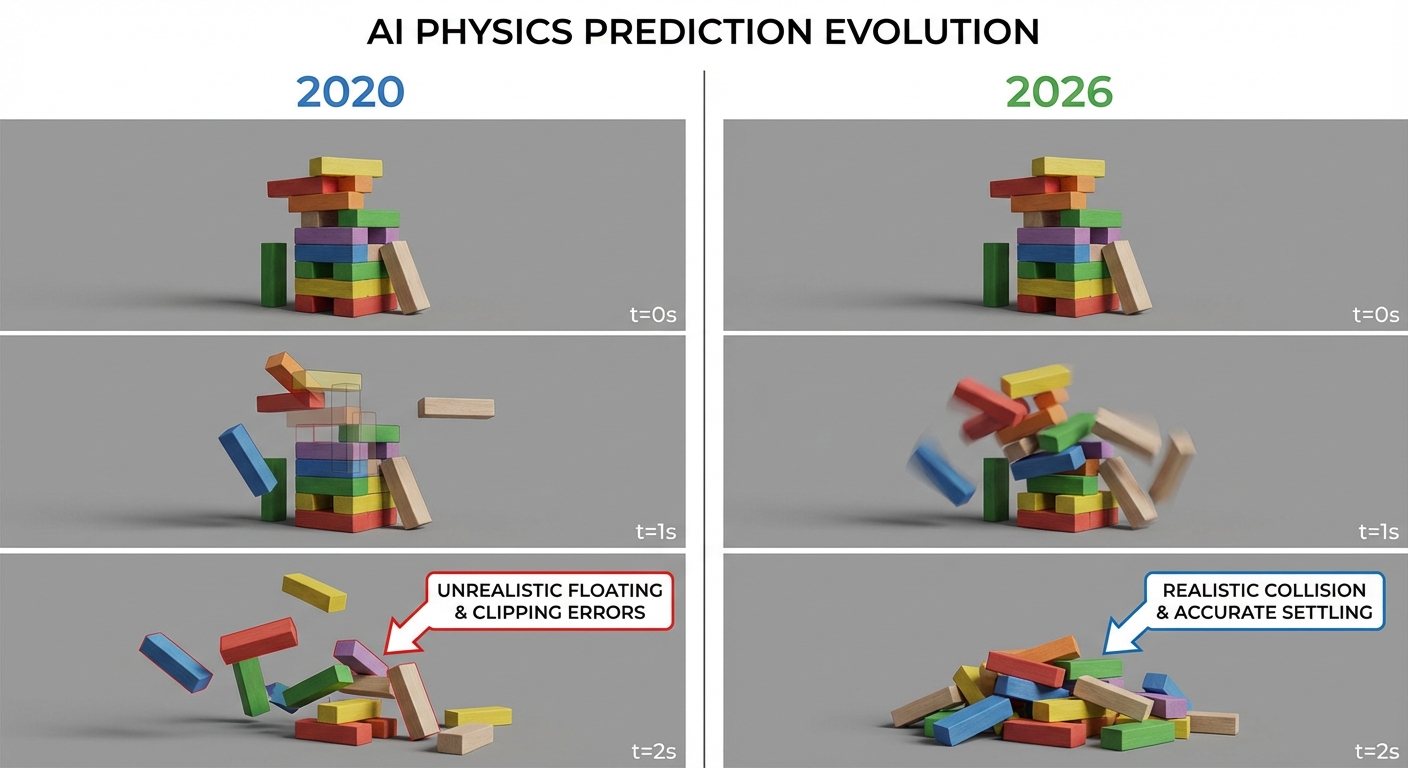

The breakthrough parallels earlier developments in language models. GPT-2 could generate coherent paragraphs but made basic logical errors. GPT-3, with more parameters and training data, demonstrated surprising reasoning abilities that emerged without explicit programming. Similarly, earlier video prediction models could forecast simple movements but struggled with complex interactions. The latest world models, trained at unprecedented scale, exhibit understanding of physics that researchers describe as almost intuitive.

These systems can now handle scenarios that would have stumped earlier AI: predicting how a stack of differently shaped objects will topple, anticipating how cloth will drape over furniture, modeling how liquids will slosh in containers being moved. They maintain consistent predictions across longer time horizons, understanding that an object pushed off a table will continue falling until it hits the ground. They demonstrate what researchers call “common sense physics,” the practical understanding of how the world works that humans develop through experience.

Major AI labs have been racing to develop world models since 2024, recognizing their potential importance. Google’s research division demonstrated systems that could predict complex physical interactions in simulated environments. Meta released models capable of understanding how humans move through and interact with 3D spaces. OpenAI has reportedly been working on world models that integrate with their language systems, potentially enabling AI that can reason about physical scenarios described in text.

The commercial implications drove significant investment. Autonomous vehicle companies need AI that understands physics to navigate safely. Robotics firms need machines that can predict the consequences of their actions. Video game developers want more realistic simulations without hand-coding every physical interaction. The market pulled the technology forward even as the science advanced it.

From Language to Physics: The Conceptual Leap

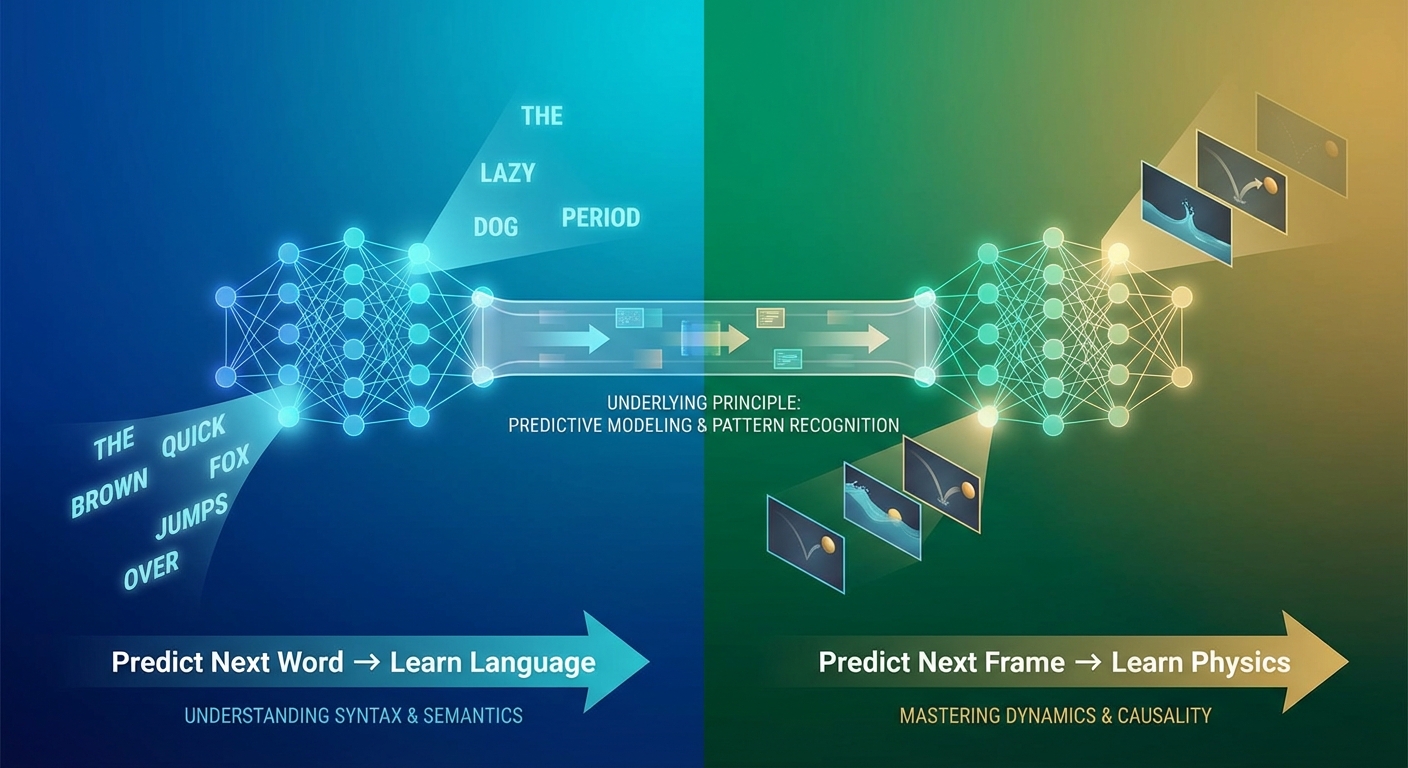

The recommendation algorithms that seem to read your mind work by finding patterns in human behavior. World models apply similar pattern-finding to physical behavior. But the conceptual leap from language AI to physics AI reveals something deeper about what these systems are learning.

Language models trained to predict the next word end up learning grammar, facts, and even forms of reasoning, none of which were explicitly taught. The task of prediction forced the development of internal representations that captured something real about language structure. World models trained to predict the next video frame are undergoing an analogous process. The task of physical prediction forces the development of internal representations that capture something real about physics.

This is striking because language and physics seem so different. Language is a human invention, arbitrary in its symbols and conventions. Physics is fundamental to reality, the same everywhere in the universe. Yet both can be learned through prediction, by observing sequences and developing expectations about what comes next. This suggests that prediction might be a universal learning principle, applicable to any domain with underlying regularities.

Some researchers see world models as evidence that AI might eventually develop general intelligence through scale and prediction alone. If predicting text produces language understanding, and predicting video produces physics understanding, perhaps predicting enough diverse data would produce something like genuine comprehension of reality. This remains speculative and controversial, but the success of world models has given the hypothesis more credibility.

Applications and Implications

The most immediate applications of world models are in robotics. Traditional robots operate in structured environments with predictable objects and interactions. They struggle in unstructured settings where they encounter novel situations: a box they’ve never seen, a surface with unexpected texture, an obstacle appearing in an unexpected place. World models could give robots the kind of adaptive common sense that lets humans navigate unfamiliar environments successfully.

Imagine a household robot tasked with clearing a cluttered table. It sees objects of various shapes and weights, some fragile, some stable, some likely to roll if bumped. A robot with a good world model could predict the consequences of different actions: if I pick up this glass first, that precarious stack might fall. If I push this plate aside, that cup might tip. This predictive capability would enable planning that accounts for physical dynamics, not just spatial geometry.

Autonomous vehicles present similar challenges at higher stakes. Self-driving cars must predict not just where other vehicles are but where they’ll be, how they’ll respond to traffic conditions, and what might happen if something unexpected occurs. Current systems rely on elaborate rules and training for specific scenarios. World models could enable more general prediction, handling situations the system has never explicitly encountered by drawing on learned physical intuitions.

Scientific applications are also emerging. Molecular dynamics simulations, used to study how proteins fold and drugs interact with biological targets, are computationally expensive because they model physics from first principles. World models trained on simulation data can learn to make predictions directly, potentially accelerating drug discovery and materials science. Climate modeling, another computationally demanding field, might benefit from similar approaches.

Video game and simulation industries have obvious interest. Game physics engines currently require extensive hand-tuning to produce realistic behavior. World models could learn realistic physics from video data, enabling games with more natural interactions. Film visual effects could use world models to predict how simulated objects should move, reducing the manual work currently required to make CGI convincing.

The Limitations and Challenges

Despite the excitement, world models face significant limitations that researchers are working to address. The systems require enormous amounts of training data, typically millions of video clips. They consume substantial computational resources, making them expensive to train and deploy. Their predictions, while improved, remain imperfect, especially for scenarios far outside the training distribution.

Generalization remains a challenge. A world model trained primarily on indoor videos may struggle with outdoor physics. One trained on rigid objects may mispredict soft-body dynamics. The breadth of physical situations in the real world is vast, and covering that breadth with training data is difficult. Researchers are exploring techniques to improve generalization, including training on diverse simulated environments where unlimited data can be generated, but progress is incremental.

There’s also a question of interpretability. We don’t fully understand what these models learn or how they make predictions. They could be picking up on superficial correlations that happen to work in training data but fail in deployment. Without understanding the internal representations, it’s hard to know when to trust predictions and when to be skeptical. This matters especially for safety-critical applications like autonomous vehicles, where failures can be catastrophic.

The relationship between learned intuitive physics and formal physics remains unclear. World models seem to capture something about how the world works, but that something isn’t equivalent to Newton’s laws. They might learn useful approximations that break down in edge cases. They might discover regularities that physicists haven’t formalized. The epistemological status of their knowledge is genuinely novel, neither human intuition nor scientific theory.

The Bigger Picture

World models represent a shift in how AI researchers think about intelligence. For decades, the field oscillated between two approaches: symbolic AI, which tried to program explicit knowledge and rules, and connectionist AI, which learned patterns from data without explicit programming. World models suggest a synthesis: learn from data, but learn representations that support the kind of reasoning symbolic AI attempted to encode.

This synthesis points toward AI that genuinely understands rather than merely mimics understanding. A language model that predicts text convincingly might not truly comprehend what words mean. But a world model that accurately predicts physical interactions demonstrates some form of physical understanding, even if it differs from human comprehension. The predictions work because the model has learned something real about reality.

The development of world models also highlights how much AI still lacks. Human physical intuition operates effortlessly, integrating visual perception, motor planning, and prediction in real time with minimal computational overhead. AI systems achieving comparable prediction require massive models, extensive training, and significant inference compute. The gap between human ease and machine difficulty suggests that biology has discovered efficient solutions we haven’t yet replicated.

Just as space exploration has seen accelerating progress through advances in both public and private sectors, AI development benefits from academic research, corporate investment, and open-source collaboration. World models are being developed across this entire ecosystem, with papers shared, models released, and techniques refined through collective effort. The pace of progress reflects this distributed innovation.

Looking ahead, world models may prove to be a crucial missing piece in artificial general intelligence, the hypothetical AI that matches or exceeds human capabilities across domains. Or they may prove to be another useful but limited tool, excellent for specific applications but not a path to general intelligence. Either way, they represent fascinating progress in teaching machines to understand the physical world through observation, much as every human child has done throughout history.

The toddler watching her ball bounce doesn’t know she’s building a world model. She just plays and learns. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about world models in AI is that they learn the same way, through play in the sense of prediction, finding patterns in sequences of events and building expectations about what comes next. In learning physics by watching, these systems remind us how extraordinary it is that watching can teach physics at all.