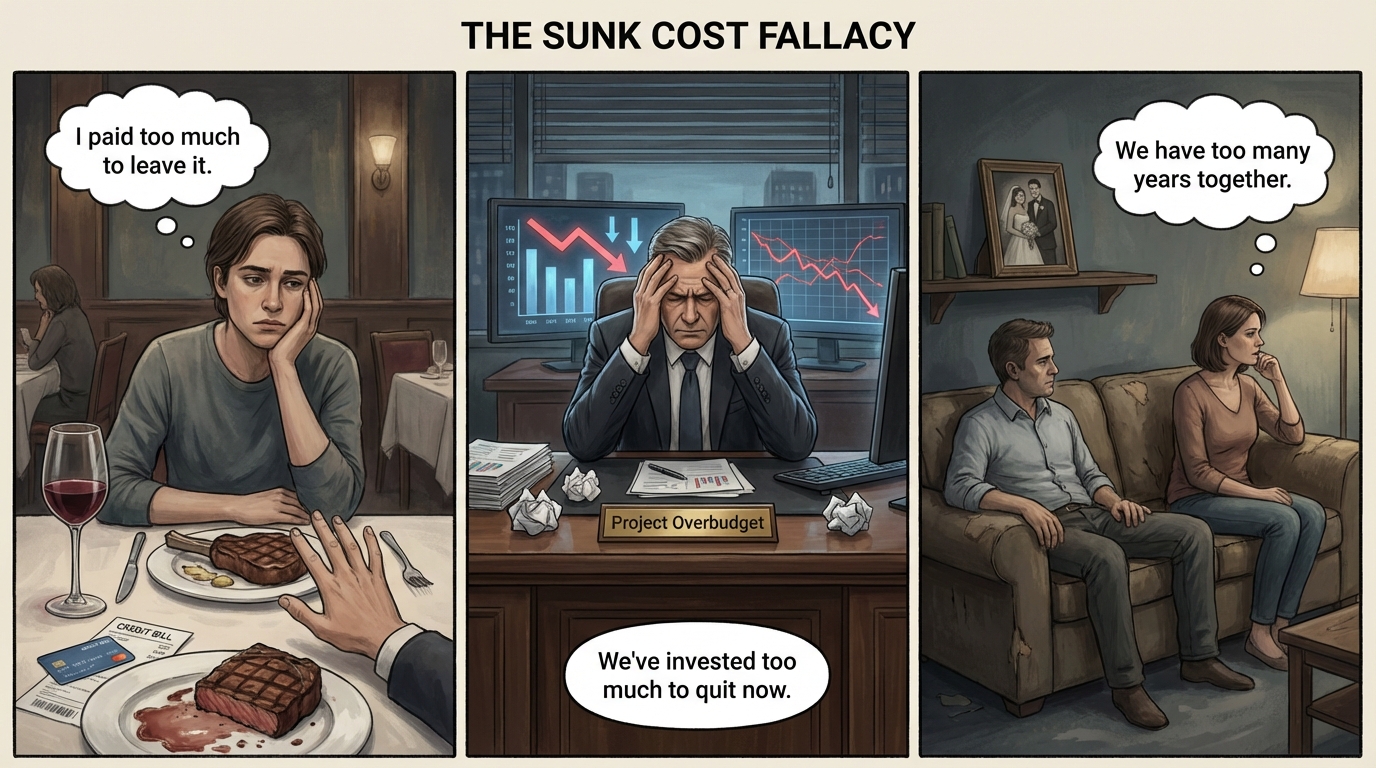

You’re ninety minutes into a terrible movie. It’s not getting better. You could leave, do something else with the remaining hour, and improve your evening immediately. But you paid for the ticket. So you stay. You sit through a film you’re not enjoying because walking out would mean “wasting” the money you already spent, even though that money is gone regardless of whether you stay or leave.

This is the sunk cost fallacy, one of the most pervasive and costly errors in human reasoning. We continue investing in failing projects, bad relationships, and losing strategies because of what we’ve already put in, even when the rational choice is clearly to cut our losses and move on. The phenomenon appears everywhere: in business decisions worth billions, in national policies affecting millions, and in the small personal choices that shape individual lives.

Understanding why we fall for this fallacy requires looking at how our minds evolved to process loss, how social pressures reinforce irrational commitment, and why the very traits that make us human also make us vulnerable to this specific cognitive trap. The sunk cost fallacy isn’t just an economic curiosity; it reveals something fundamental about how we construct meaning from our choices and investments.

What Makes a Cost “Sunk”

A sunk cost is any resource, whether money, time, or effort, that has been spent and cannot be recovered regardless of future actions. The movie ticket is a classic example: once purchased and the showtime passed, that money is gone whether you watch the film or not. Staying for the ending doesn’t recoup anything; leaving early doesn’t lose anything additional. The cost is sunk.

Economists define rationality as making decisions based on future costs and benefits, ignoring sunk costs entirely. This isn’t cold or heartless; it’s simply logical. What matters for any decision is what lies ahead: what will the remaining hour of this movie cost me in time and enjoyment? What might I gain by doing something else instead? What I’ve already spent is irrelevant to this calculation because I can’t get it back either way.

Yet humans consistently fail to reason this way. Studies dating back to the 1980s have documented the phenomenon rigorously. In one famous experiment, researchers Hal Arkes and Catherine Blumer asked people to imagine they’d bought tickets to two ski trips scheduled for the same weekend, one for fifty dollars and one for twenty-five. The fifty-dollar trip was to a less desirable location. Forced to choose which trip to take, most people chose the inferior trip, simply because they’d paid more for it. They sacrificed a better experience to avoid “wasting” a larger sunk cost.

The Psychology Behind the Trap

Several psychological mechanisms drive our susceptibility to sunk costs, and they operate largely outside conscious awareness. The most powerful is loss aversion, documented extensively by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Humans experience losses more intensely than equivalent gains. Losing twenty dollars feels worse than finding twenty dollars feels good, by roughly a factor of two. This asymmetry means we’ll work harder to avoid losses than to secure gains, even when the expected value is the same.

When we consider abandoning a project or relationship where we’ve already invested heavily, we frame leaving as crystallizing a loss. All that time and money becomes definitively wasted. Continuing, even irrationally, preserves the possibility, however slim, that our investment might still pay off. We’re not really evaluating the remaining opportunity objectively; we’re avoiding the emotional pain of admitting a loss.

There’s also a deep need for psychological consistency at work. We like to believe our past decisions were good ones. Abandoning a project means acknowledging we were wrong to start it, wrong to continue it, wrong at multiple points along the way. The human ego resists this acknowledgment. It’s easier to throw good money after bad than to admit the money was never good in the first place.

Social pressure compounds these internal biases. Nobody wants to be seen as a quitter. We worry about what others will think if we abandon projects, relationships, or commitments. Leaders face particular pressure: admitting a major initiative was a mistake can be career-ending. It’s often personally safer to continue a failing strategy and blame external factors than to acknowledge error and change course, even when changing course would serve the organization better.

Where Sunk Costs Do the Most Damage

The sunk cost fallacy scales. Personal decisions about whether to finish a mediocre book or eat the rest of an oversized meal have limited consequences. But the same cognitive bias operating in corporate boardrooms and government policy can waste billions and cost lives.

The Concorde supersonic jet became the textbook case for economists, so much so that the sunk cost fallacy is sometimes called the “Concorde fallacy.” Both the British and French governments continued funding the aircraft long after it became clear the program would never be economically viable. Internal projections showed the plane would lose money for decades, if not forever. But so much had already been spent that stopping felt impossible. The sunk costs, and national prestige, drove continued investment in a known money loser for decades.

Wars often continue past the point of rationality for similar reasons. The Vietnam War saw American policymakers repeatedly escalate commitment partly to justify previous sacrifice. We can’t let those soldiers have died in vain became a reason to send more soldiers to die. The sunk cost wasn’t money; it was lives, which made the psychological pressure to continue even more intense. Cutting losses would have meant admitting the previous losses were pointless, an unbearable conclusion.

In business, sunk costs explain why companies persist with failing product lines, unprofitable divisions, and strategies that clearly aren’t working. Leaders who championed the original decision are especially reluctant to kill it. Bringing in outside executives, with no personal investment in past choices, often leads to rapid cuts that insiders couldn’t make despite knowing they were necessary.

Breaking Free: Strategies That Work

The first step in overcoming the sunk cost fallacy is simply knowing it exists. Awareness doesn’t eliminate the bias, but it creates space to question whether commitment is rational or merely habitual. When you feel reluctant to quit something, ask yourself: if I hadn’t already invested this time and money, would I start this project today? If the answer is no, the previous investment is distorting your judgment.

Creating decision points in advance helps separate past investment from future choices. Businesses can establish “kill criteria” before launching projects: specific conditions under which the project will be terminated regardless of resources already committed. Personal versions might include setting a time limit on relationships or projects: if this isn’t working by a certain date, I’ll move on regardless of what I’ve put in.

Reframing loss can reduce the emotional sting that drives irrational persistence. Instead of viewing an abandoned project as wasted investment, consider it tuition paid for learning. The failed startup taught you about markets and management. The ended relationship clarified what you need from a partner. The sunk costs bought something, just not what you originally intended.

Seeking outside perspective is particularly valuable because the sunk cost fallacy is easier to see in others than in ourselves. Friends can evaluate your situation without the ego involvement that clouds your judgment. Advisors and mentors who weren’t part of the original decision can assess the future opportunity with fresh eyes. Sometimes we need permission to quit, and others can provide it.

Organizations increasingly build structures that counteract the sunk cost fallacy systematically. Amazon famously requires teams to write “pre-mortems” before launching projects, imagining in advance why the project might fail. This mental exercise makes future failure more vivid and easier to acknowledge when warning signs appear. Regular review cycles, with explicit authority to kill projects, normalize the act of cutting losses rather than stigmatizing it.

The Bigger Picture

The sunk cost fallacy reveals a tension at the heart of human psychology. Many of the traits that make us vulnerable to this error are actually strengths in other contexts. Commitment to relationships and projects, the ability to persist through difficulty, reluctance to give up on things we’ve worked hard for, loyalty to people and institutions: these are generally virtues. They help us build things that take time, maintain relationships through rough patches, and achieve goals that require sustained effort.

The problem is that our commitment mechanisms don’t come with precise calibration. We can’t easily distinguish between healthy persistence and irrational stubbornness, between loyalty and being taken advantage of, between seeing a project through and throwing good effort after bad. The same psychological wiring that helps us finish difficult but worthwhile endeavors also traps us in failing ones.

Understanding this doesn’t make the sunk cost fallacy disappear, but it does offer a different relationship with it. We can notice when we’re reluctant to quit something and ask whether commitment is serving us or imprisoning us. We can build structures and relationships that help us see clearly when we’re too invested to see ourselves. And we can practice, in small ways, the skill of walking away from movies, meals, and minor investments when they’re no longer worth our time.

Every hour spent finishing something that isn’t working is an hour not spent starting something that might. Every dollar chasing a sunk cost is a dollar not invested in future opportunity. The past is genuinely gone, whether we accept that or not. The only question is whether we’ll make decisions based on what’s ahead or remain prisoners of what’s behind.