In the summer of 1950, physicist Enrico Fermi was walking to lunch with colleagues at Los Alamos National Laboratory when the conversation turned to flying saucers. The topic was in the news; there had been reports of unidentified objects, and the scientists joked about the possibility of alien visitors. But as they sat down to eat, Fermi suddenly asked a question that would haunt astronomy for decades: “Where is everybody?”

His colleagues understood immediately what he meant. The galaxy is billions of years old. It contains hundreds of billions of stars. If even a tiny fraction of those stars have planets, and even a tiny fraction of those planets develop life, and even a tiny fraction of that life becomes intelligent, the galaxy should be teeming with civilizations, many of them millions of years more advanced than ours. Such civilizations, given enough time, could have colonized the entire galaxy. Yet we see no evidence of them. No signals, no artifacts, no visitors. The universe appears empty.

This contradiction between the mathematical expectation of abundant alien life and the absence of any evidence for it became known as the Fermi Paradox. It has generated hundreds of proposed solutions, ranging from the optimistic to the terrifying. And now, with our exponentially expanded knowledge of exoplanets and the search for life, we’re finally in a position to evaluate these solutions against actual data. The answer that’s emerging may be the most unsettling of all.

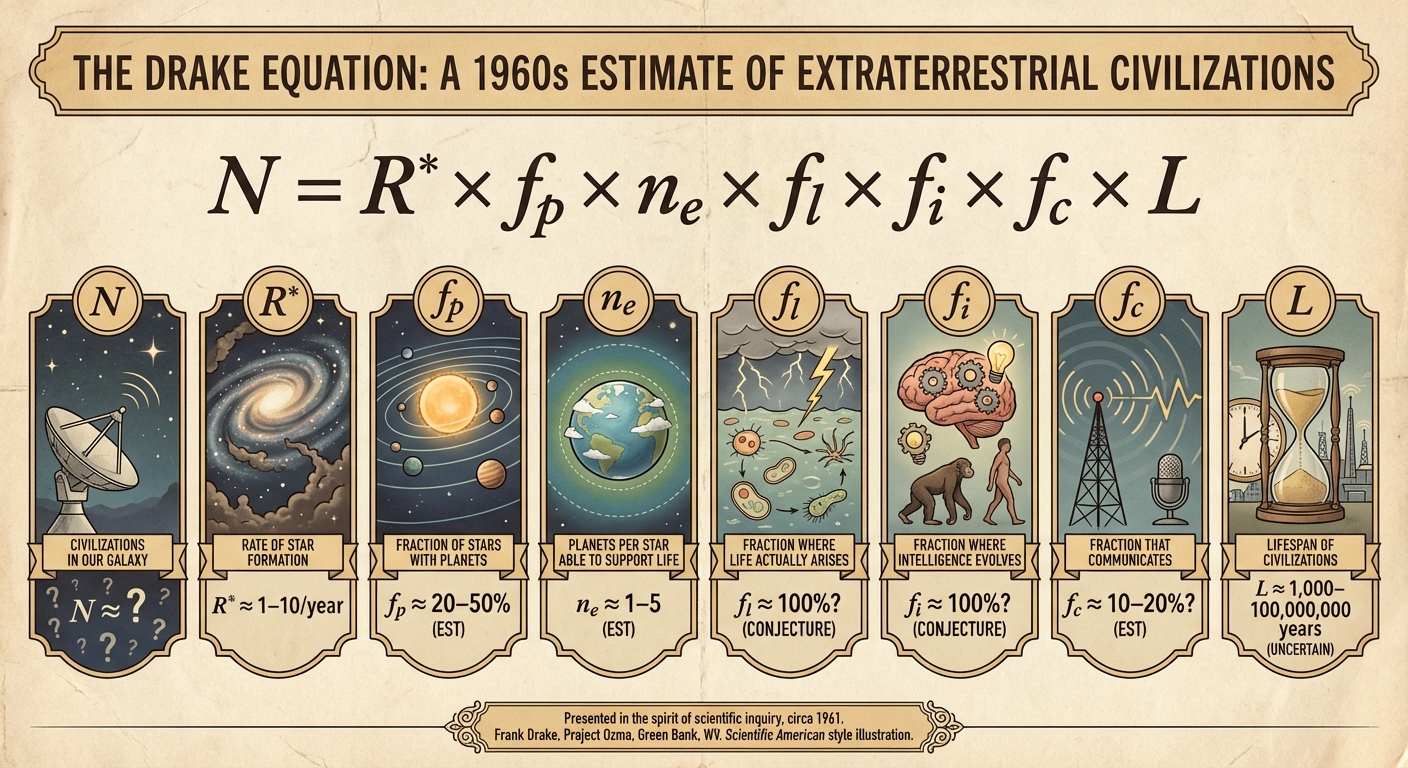

The Drake Equation: Quantifying Our Ignorance

In 1961, astronomer Frank Drake proposed an equation to estimate the number of communicating civilizations in the Milky Way. The Drake Equation multiplies several factors together: the rate of star formation, the fraction of stars with planets, the fraction of planets that could support life, the fraction where life actually develops, the fraction where intelligence evolves, the fraction that develop technology, and the average lifespan of technological civilizations.

When Drake first proposed the equation, most of its terms were complete unknowns. We had no confirmed planets outside our solar system. We knew of only one planet where life existed, one where intelligence had evolved, and one where technology had developed. The equation wasn’t meant to produce precise answers; it was meant to organize our ignorance, showing which questions mattered and where more research was needed.

Today, we can fill in several terms with surprising precision. The Kepler space telescope, which operated from 2009 to 2018, discovered thousands of exoplanets. Statistical analysis of its data suggests that nearly every star in the galaxy has at least one planet, and about one in five Sun-like stars has an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone where liquid water could exist. The James Webb Space Telescope has begun analyzing exoplanet atmospheres, searching for biosignatures. We’ve gone from knowing of zero exoplanets to confirming over 5,500, with thousands more candidates awaiting verification.

The numbers are staggering. The Milky Way contains an estimated 200 to 400 billion stars. If even 20 percent have potentially habitable planets, that’s 40 to 80 billion candidates for life. Even if life is vanishingly rare, emerging on only one in a million such planets, we’d expect tens of thousands of life-bearing worlds in our galaxy alone. If intelligence and technology are similarly rare one-in-a-million events after life appears, we’d still expect tens of civilizations currently existing.

But here’s where the paradox bites. The galaxy is 13 billion years old. A civilization with our technology could colonize the entire galaxy in perhaps 10 million years, using self-replicating probes or generation ships, even without faster-than-light travel. That’s a cosmic eyeblink. If any civilization arose even a billion years before us, they’ve had time to colonize everything a hundred times over. Where are they?

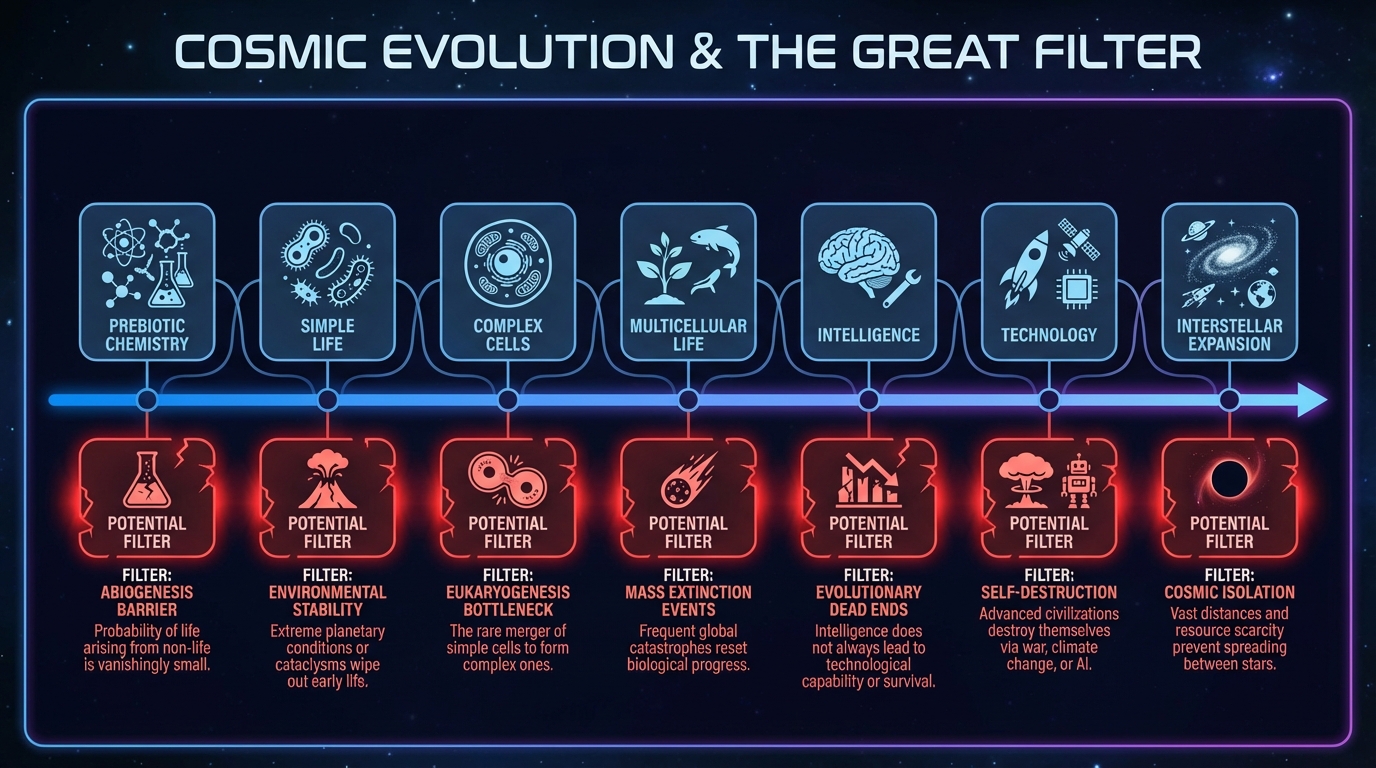

The Great Filter: Something Is Killing Civilizations

One family of solutions to the Fermi Paradox involves what philosopher Nick Bostrom calls the “Great Filter.” Somewhere along the path from dead matter to galaxy-spanning civilization, there must be a step that almost never happens. A filter blocks progress, preventing the emergence of the spacefaring civilizations we’d otherwise expect.

The hopeful possibility is that the Great Filter lies behind us. Perhaps the origin of life is astronomically unlikely, happening only once in a trillion trillion planets despite favorable conditions. Perhaps the evolution of eukaryotic cells (complex cells with nuclei) is the bottleneck, or the emergence of multicellular life, or the development of intelligence, or the invention of technology. If any of these steps is nearly impossible, the silence of the universe makes sense: we’re alone because we’re the fluke that made it through.

The terrifying possibility is that the Great Filter lies ahead of us. Perhaps civilizations develop to roughly our level and then consistently destroy themselves. Nuclear war, engineered pandemics, artificial intelligence gone wrong, or some technology we haven’t yet invented might be civilizational time bombs. This hypothesis would explain the silence: intelligent species arise frequently, but they always self-destruct before achieving interstellar presence. If this is true, our future is almost certainly short.

Recent evidence has complicated the Filter calculations. The discovery of extremophile organisms thriving in Earth’s harshest environments suggests life might be hardier than assumed. The apparent rapid emergence of life after Earth became habitable (within a few hundred million years) suggests the origin of life might not be terribly unlikely. The search for life in places like the deep ocean reveals environments previously thought sterile actually teeming with organisms. If life is easy, the Filter must lie elsewhere.

Conversely, the fact that intelligence arose only once in Earth’s four-billion-year history, despite millions of species having existed, suggests intelligence might be the rare step. Many evolutionarily successful organisms, from bacteria to sharks, never developed anything resembling minds. Perhaps intelligence is a costly specialization that rarely provides enough survival advantage to evolve, making Earth’s technological civilization a genuine cosmic rarity.

Alternative Hypotheses: Why We Might Be Missing Them

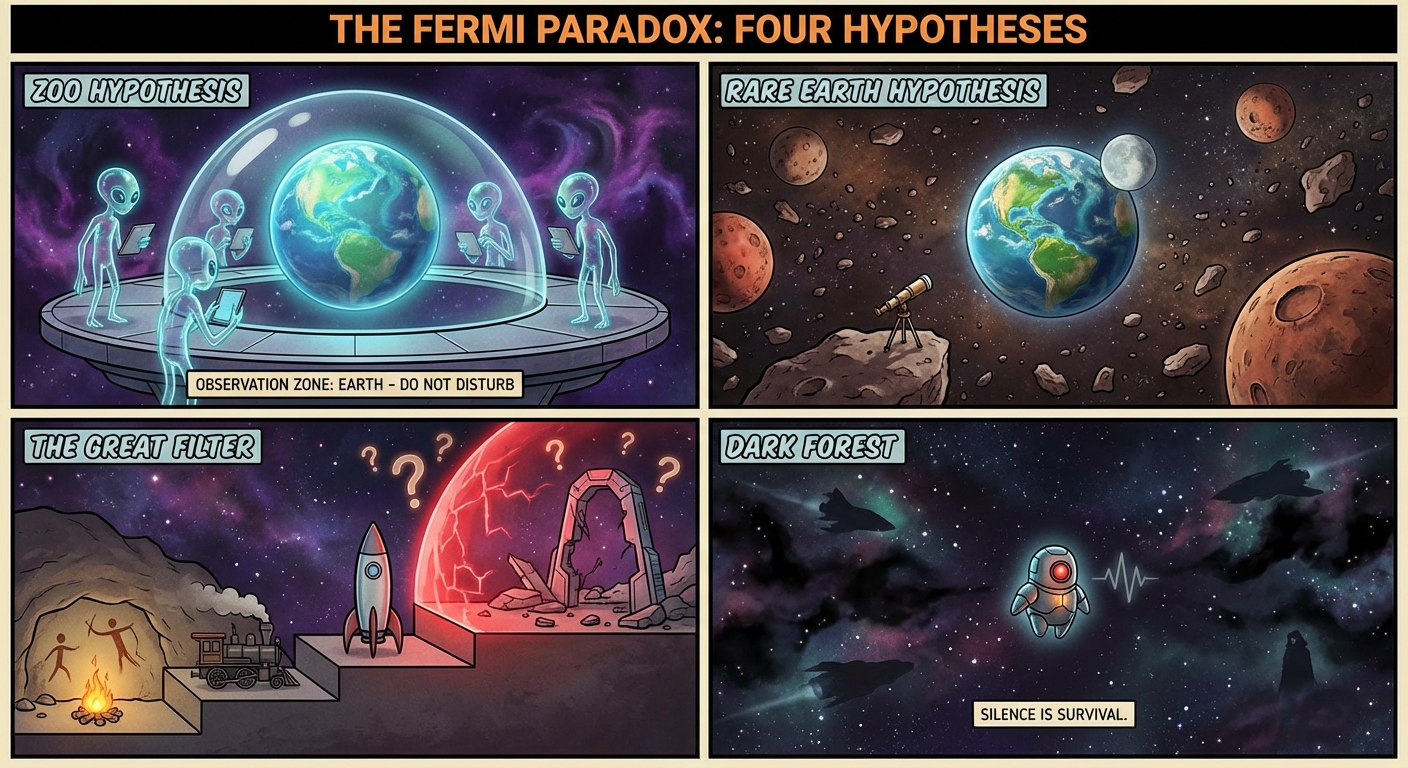

Not all solutions to the Fermi Paradox invoke filters. Perhaps civilizations exist but we haven’t detected them for less alarming reasons. These hypotheses preserve both the possibility of abundant alien life and optimism about humanity’s future.

The Zoo Hypothesis proposes that advanced civilizations are aware of us but deliberately avoid contact, perhaps to allow our natural development or because we don’t meet some threshold of interest. We might be like a nature preserve, observed but not interfered with. This seems anthropocentric, assuming aliens would care about our development, but it can’t be ruled out.

The Rare Earth Hypothesis suggests that while simple life might be common, the specific conditions enabling complex life and intelligence, including a stable star, protective gas giants, a large moon, plate tectonics, and liquid water, occur together only extremely rarely. Earth might be genuinely unusual, a winner of multiple cosmic lotteries. The growing catalog of exoplanets lets us test this hypothesis; so far, we haven’t found Earth’s precise configuration elsewhere, but the search has barely begun.

The Dark Forest Hypothesis, popularized by Liu Cixin’s science fiction trilogy, proposes something more ominous. In a universe where civilizations can’t verify each other’s intentions, and where destruction is easier than communication, the safest strategy might be silence. Any civilization that broadcasts its presence risks being annihilated by more advanced civilizations practicing preemptive defense. The galaxy might be full of life, all hiding from each other, all afraid to speak first. If this is true, our radio broadcasts have been monumentally foolish.

The Transcension Hypothesis suggests that advanced civilizations don’t expand outward into space but inward into computational realms. Perhaps technological species discover that the most interesting frontiers are virtual, exploring vast possibility spaces in simulated realities rather than the relatively limited physical universe. Such civilizations would be invisible to us, having retreated into forms we can’t detect with our instruments.

What the James Webb Space Telescope Is Teaching Us

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in late 2021 and fully operational since 2022, represents humanity’s most powerful tool for addressing the Fermi Paradox. Its unprecedented sensitivity allows detection of atmospheric compositions on exoplanets dozens of light-years away. If life exists on those worlds, it might be altering their atmospheres in detectable ways.

The search focuses on biosignatures: molecules that, in combination, strongly suggest biological activity. Oxygen by itself isn’t definitive; geological processes can produce it. But oxygen together with methane indicates chemistry that shouldn’t persist without ongoing production, typically biological. JWST can detect these molecular fingerprints in the light passing through exoplanet atmospheres during transits.

Early results have been tantalizing but not conclusive. JWST detected carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere of a hot Jupiter, demonstrating its analytical capabilities. It found water vapor in the atmosphere of a super-Earth in the habitable zone, though likely too hot for life as we know it. The telescope is now examining the most promising targets: Earth-sized planets in the habitable zones of nearby red dwarf stars, including the TRAPPIST-1 system with its seven rocky worlds.

What we haven’t found is equally significant. No unambiguous biosignatures yet. No signs of artificial structures or industrial pollution in exoplanet atmospheres. No technosignatures, indicators of technological activity. The silence continues, now at a finer resolution than ever before.

This absence is beginning to constrain our estimates. The exponentially improving pace of space exploration means we’re surveying more of the cosmos more thoroughly. Each negative result, each potentially habitable world showing no signs of life, shifts the probability distribution. Either life is rarer than we hoped, or it takes forms we can’t detect, or something else we haven’t considered is going on.

The Bigger Picture

The Fermi Paradox matters beyond academic curiosity because its solutions have profound implications for humanity’s future. If the Great Filter lies behind us, we might be destined for the stars. If it lies ahead, we need to identify and avoid it. If civilizations routinely destroy themselves, we need to understand why and whether we can be different. If the Dark Forest hypothesis is true, we may have already endangered ourselves by broadcasting our presence.

The paradox also challenges our sense of cosmic significance. We grew up in a culture shaped by the Copernican principle: Earth isn’t the center of the universe, humanity isn’t specially created, we’re probably typical. But if intelligent life is genuinely rare, if we’re among the first technological species in our galaxy, that assumption inverts. We might matter more than we thought, not because of divine favor but because of cosmic circumstance.

There’s something poignant about the search itself. We’ve been listening for signals for over sixty years, since Frank Drake pointed a radio telescope at nearby stars in 1960. We’ve sent messages into the void, hopeful that someone might respond. The silence has been complete. Every day that passes without contact is data, evidence that whatever we’re looking for isn’t there, at least not in the forms we’re seeking.

Perhaps the deepest lesson of the Fermi Paradox is epistemic humility. We don’t know what we don’t know. Our models of civilization, intelligence, and technology are based on exactly one example: ourselves. Alien intelligence, if it exists, might be so different from us that we couldn’t recognize it or communicate with it. The silence might reflect not absence but incomprehension, two minds so different they can’t even identify each other as minds.

Enrico Fermi ate his lunch that day and went back to work. The question he raised over sandwiches has outlived him by nearly seventy-five years, growing more urgent as our knowledge expands and the silence persists. Where is everybody? We still don’t know. But we’re getting better at knowing what we don’t know, and that might be progress enough.