In 1960, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh descended nearly 36,000 feet to the bottom of the Mariana Trench in the bathyscaphe Trieste. What they saw through their tiny porthole was, in one sense, nothing at all. Complete darkness. No sunlight reaches the ocean floor; it gets absorbed by seawater long before reaching those depths. But what makes the deep ocean strange isn’t just the absence of light. It’s that life down there evolved to create its own.

The deep ocean is darker than outer space, where starlight, reflected light from planets, and the glow of distant galaxies provide at least some illumination. At the ocean floor, there’s no external light source whatsoever. The pressure is immense, the temperature hovers near freezing, and yet life thrives in this crushing darkness. Understanding how it does so reveals something profound about the nature of light, life, and the unexpected places where evolution finds solutions.

Where Light Goes to Die

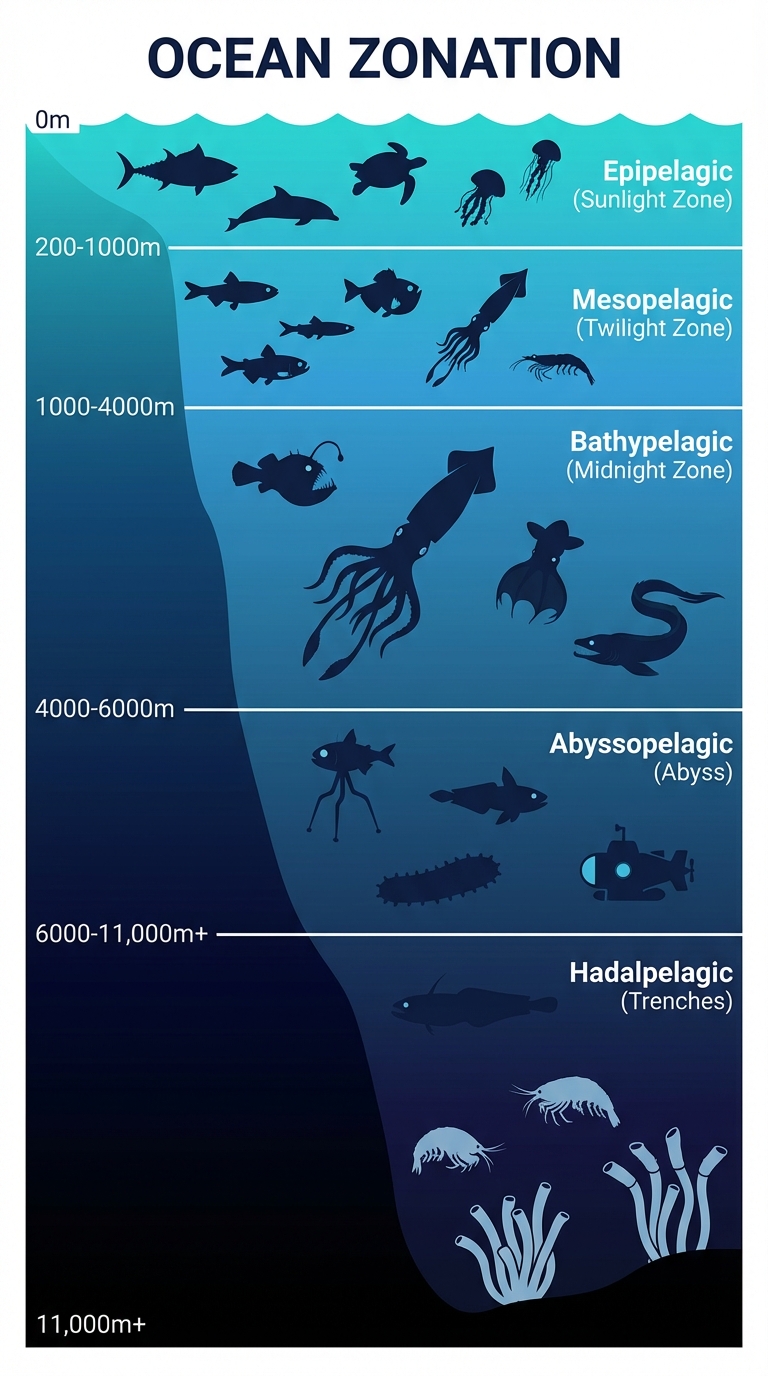

Sunlight penetrates ocean water in predictable stages. The top 200 meters, called the epipelagic or sunlight zone, receive enough light for photosynthesis. This is where most marine life we’re familiar with lives: fish, whales, coral reefs, and the photosynthetic plankton that produce half the oxygen we breathe. Below that lies the mesopelagic or twilight zone, from 200 to 1,000 meters, where only dim blue light filters through. By 1,000 meters, essentially all sunlight has been absorbed.

Below 1,000 meters begins the bathypelagic zone, the “midnight zone,” which extends to about 4,000 meters. This is complete darkness by human standards, but the creatures here have evolved eyes so sensitive that even the faintest bioluminescent flash can be detected. The abyssopelagic zone runs from 4,000 to 6,000 meters, covering the vast abyssal plains that comprise most of the ocean floor. Finally, the hadopelagic zone encompasses the deepest trenches, below 6,000 meters, places like the Mariana Trench where Piccard and Walsh made their historic dive.

Water absorbs light with remarkable efficiency compared to air. Even in the clearest tropical waters, only about 1% of surface light reaches 100 meters. The red wavelengths are absorbed first, within the top few meters, which is why underwater photographs at depth appear blue unless artificial light is used. Blue light penetrates deepest, but even it is fully absorbed by 1,000 meters in the clearest conditions. In typical ocean water with suspended particles, effective darkness comes much sooner.

Space, by contrast, is full of light. While empty interstellar regions might seem dark, they’re illuminated by starlight from every direction, the cosmic microwave background radiation, and the zodiacal light from dust in our solar system. A camera exposure in deep space will capture this ambient light. At the bottom of the ocean, even an infinite exposure would capture nothing but the black of absolute absence.

Bioluminescence: Evolution’s Flashlight

When external light sources disappear entirely, organisms that need to see, communicate, hunt, or attract mates face a fundamental problem. Evolution’s solution was bioluminescence: the ability to produce light through chemical reactions within living tissue. The deep ocean is the most bioluminescent environment on Earth, with an estimated 90% of animals in the midnight zone capable of producing their own light.

The chemistry behind bioluminescence involves a light-producing molecule called luciferin and an enzyme called luciferase. When oxygen reacts with luciferin in the presence of luciferase, photons are emitted. Different organisms have evolved this capability independently at least 40 different times, using various luciferin molecules, suggesting the selective advantage of producing light in the deep sea is immense.

The applications of bioluminescence in the deep sea are remarkably diverse. Anglerfish dangle luminous lures to attract prey directly into their jaws. Some squid and fish use ventral photophores to create counter-illumination, matching the faint downwelling light to erase their silhouette from predators looking up. Dinoflagellates, tiny single-celled organisms, flash when disturbed, potentially alerting larger predators to the presence of whatever disturbed them, a kind of “burglar alarm” defense that gets the disturber eaten. Some shrimp spit bioluminescent chemicals at predators, dazzling them like underwater flashbangs.

The viperfish has photophores inside its mouth, essentially baiting prey to swim directly in. The flashlight fish has organs under its eyes that harbor bioluminescent bacteria, which it can reveal or hide using specialized tissue flaps. Cookie-cutter sharks use bioluminescence for camouflage except for a small dark patch that resembles a smaller fish, luring larger predators to investigate and getting bitten in turn, a kind of weaponized mimicry.

Life in Crushing Darkness

The deep ocean presents challenges beyond darkness. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the pressure exceeds 1,000 atmospheres, over 15,000 pounds per square inch. An unprotected human would be crushed instantly. Yet amphipods, fish, and single-celled organisms thrive at these pressures.

Deep-sea creatures have evolved proteins and cell membranes that function under extreme pressure. Their cell membranes contain different lipid compositions that remain fluid rather than solidifying under compression. Their enzymes are adapted to function optimally at high pressure, though these same enzymes often don’t work at surface pressure, which is why bringing deep-sea specimens to the surface typically kills them.

The food supply in the deep ocean is paradoxically both scarce and reliable. Very little organic matter sinks from the productive surface waters to the ocean floor, but what does sink tends to arrive predictably. “Marine snow,” consisting of dead plankton, fecal pellets, and other organic debris, drifts slowly downward, taking weeks to reach the abyssal plains. Occasionally, a whale carcass sinks to the bottom and becomes a “whale fall,” a bonanza that can sustain an entire ecosystem for decades.

Hydrothermal vents, discovered only in 1977, represent an entirely different energy source for deep-sea life. Where tectonic plates spread apart, superheated water laden with hydrogen sulfide and minerals jets from the seafloor. Chemosynthetic bacteria harness the chemical energy in hydrogen sulfide the way plants harness sunlight, forming the base of food webs that include giant tube worms, ghostly white crabs, and specialized fish. These ecosystems exist completely independently of solar energy, raising profound questions about where life might exist elsewhere in the universe, perhaps on moons with subsurface oceans like Europa or Enceladus.

What We Still Don’t Know

Despite covering over 70% of Earth’s surface and comprising 95% of the planet’s livable space, the deep ocean remains largely unexplored. We have better maps of Mars than of our own ocean floor. Estimates suggest that between one-third and two-thirds of deep-sea species remain undiscovered.

Each deep-sea expedition reveals new species. In 2020 alone, researchers discovered over 100 potentially new species in a single expedition to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific. Many of these creatures are small, soft-bodied organisms that disintegrate when brought to the surface, requiring specialized sampling techniques to study properly.

The challenges of deep-sea exploration are extreme. Equipment must withstand enormous pressures, temperatures near freezing, and complete darkness. Until recently, the only way to reach the deepest parts of the ocean was in specialized submersibles, which are expensive to build and operate, and carry significant risk. Only three expeditions have ever reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench: Piccard and Walsh in 1960, James Cameron in 2012, and Victor Vescovo in 2019.

Remote operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) are expanding our ability to explore deep-sea environments without risking human lives. These robots can spend weeks mapping seafloor terrain, collecting samples, and filming creatures in their natural habitat. But even with advancing technology, the sheer size of the deep ocean means comprehensive exploration will take generations.

The Bigger Picture

The deep ocean represents Earth’s last true frontier, a realm as alien as any planet in our solar system, yet accessible with sufficient technology. Understanding life in this environment does more than satisfy curiosity. It expands our conception of where and how life can exist.

Bioluminescence in the deep sea demonstrates evolution’s creativity in solving fundamental problems. When external light sources disappear, organisms evolve to make their own. When food is scarce, creatures develop metabolisms that can wait years between meals. When pressure would crush ordinary cells, specialized biochemistry enables function. Life finds ways.

The implications extend beyond Earth. If life can thrive in the crushing darkness of Earth’s ocean trenches, fueled by chemical energy from hydrothermal vents rather than sunlight, similar life might exist beneath the ice shells of Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s moon Enceladus. The discovery of chemosynthetic ecosystems fundamentally changed our models of where to search for extraterrestrial life.

For now, the deep ocean keeps most of its secrets. We’ve explored less than 20% of it in any detail. Somewhere down there, in the absolute darkness below the twilight zone, creatures are flashing signals to each other in a language of light we’re only beginning to understand. The darkness isn’t empty. It’s full of life that learned to carry its own light.

Sources: NOAA Ocean Exploration, Deep Sea Research Part I, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Nature: Marine Biology