When researchers show babies something new, most infants look at it briefly, process what they’re seeing, and move on. But some babies look longer. They stare at novel objects with an intensity that seems almost out of proportion, as if they’re trying to extract every possible bit of information from what they’re witnessing. According to new longitudinal research, these unusually curious infants tend to grow into unusually intelligent children. The connection between early curiosity and later cognitive ability turns out to be remarkably strong, suggesting that the drive to understand the world may be as fundamental to intelligence as the capacity to understand it.

The study, which followed children from infancy through early childhood, measured curiosity by presenting 8-month-old babies with sequences of images and recording how long they looked at novel items versus familiar ones. Babies who showed heightened sensitivity to novelty, spending significantly more time examining things they hadn’t seen before, scored higher on standardized IQ tests three years later. The correlation held even after controlling for factors like socioeconomic status and parental education, suggesting that curiosity itself rather than environmental advantages was driving the connection.

This finding adds to a growing body of research reframing how we think about intelligence. For decades, the dominant view treated intelligence as a capacity, a fixed mental resource that determines how well someone can solve problems or learn new skills. The curiosity research suggests intelligence might be better understood as an appetite, a drive to seek out and engage with information that shapes cognitive development from the earliest months of life. The babies who stared longest at new things weren’t just demonstrating existing intelligence. They were feeding the process that would make them more intelligent.

What Infant Curiosity Actually Looks Like

Measuring curiosity in babies requires creativity because infants can’t answer questions or follow complex instructions. Researchers rely instead on looking behavior, specifically a phenomenon called habituation. When you show a baby the same image repeatedly, they initially look at it with interest, then gradually look away as they become bored or satisfied. When you then show something new, most babies turn back to look. The degree to which they reorient to novel stimuli, and how long they maintain attention, provides a window into their information-seeking behavior.

The babies who showed the strongest curiosity in the longitudinal study weren’t just looking at new things longer. They were processing information more efficiently, habituating to familiar images faster and showing sharper discrimination between novel and familiar items. This suggests their extended looking wasn’t simply slower processing. It was deeper processing, a more thorough extraction of information from each new encounter. They were curious and capable, and the combination of drive and capacity appeared to set a trajectory for cognitive development.

The researchers also found that different aspects of curiosity predicted different cognitive outcomes. Infants who showed strong visual preferences for complexity, drawn to intricate patterns over simple ones, developed stronger spatial reasoning abilities. Those who showed heightened responsiveness to social stimuli, particularly faces displaying emotional expressions, developed stronger language skills. Curiosity appears to be not one thing but many, a family of information-seeking behaviors that channel cognitive development in specific directions.

This specificity has important implications for understanding how intelligence develops. Rather than a general cognitive resource that improves across the board, intelligence may emerge from the accumulation of knowledge and skills in particular domains, driven by domain-specific curiosities. The infant who can’t stop staring at faces may be building the foundation for social intelligence. The infant drawn to mechanical objects may be developing intuitions about physics. Early curiosity doesn’t just predict later intelligence. It may actually shape what kind of intelligence develops.

The Feedback Loop Between Curiosity and Ability

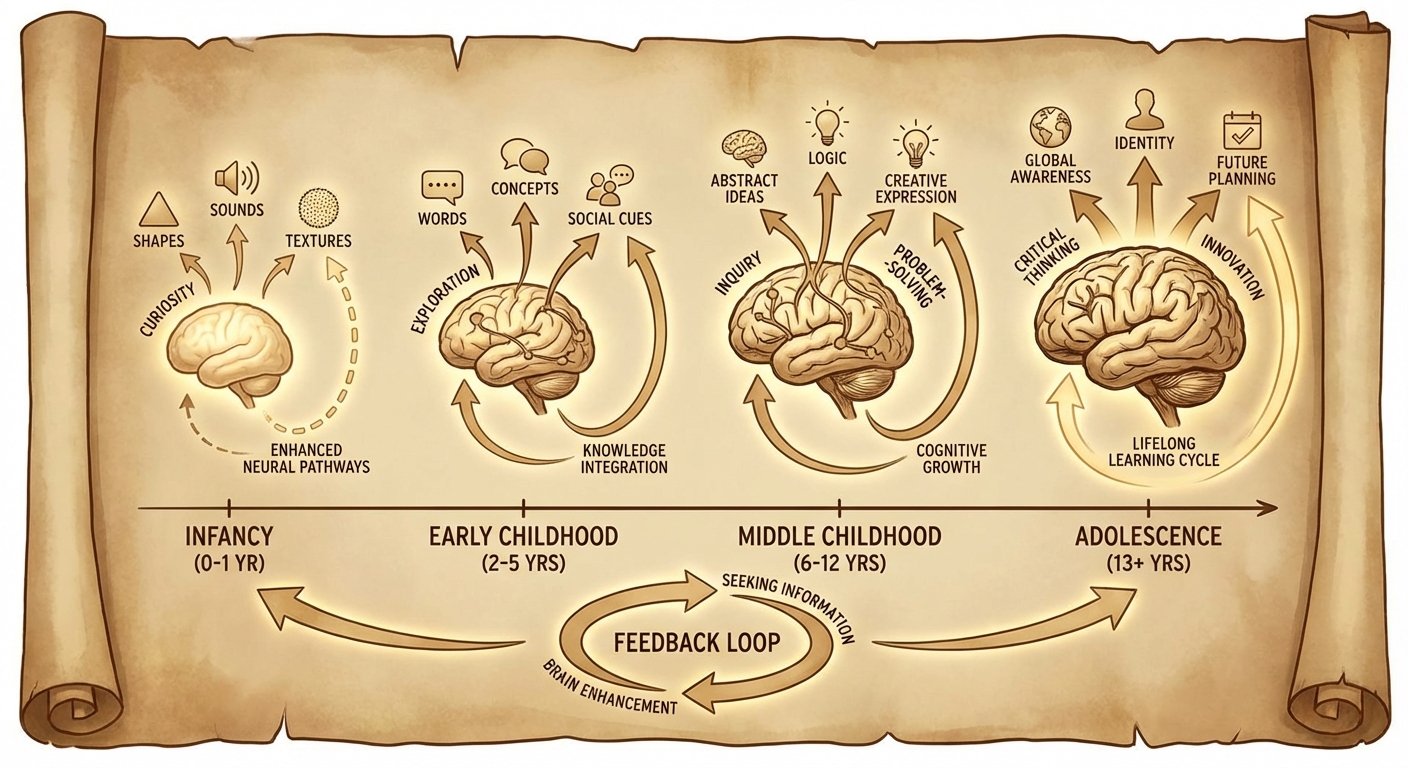

One of the most intriguing aspects of the research is the suggestion of a feedback loop between curiosity and cognitive ability. Curious infants seek out more information, which builds knowledge and skills, which enables them to recognize more novelty, which fuels more curiosity. Meanwhile, less curious infants engage less with their environment, develop knowledge more slowly, and have fewer opportunities to become intrigued by what they don’t yet understand. Over time, small initial differences in curiosity could compound into large differences in cognitive development.

This feedback loop helps explain why early intervention programs sometimes show lasting effects on cognitive outcomes. Programs that expose infants to rich, varied environments may not just be providing information directly. They may be activating and strengthening the curiosity systems that drive ongoing information seeking. The baby who experiences more novelty may develop a stronger habit of seeking novelty, creating a self-sustaining cycle of engagement with the world.

The feedback model also suggests why curiosity differences might be relatively stable over development. Research has found that babies who show high curiosity at 8 months tend to show high curiosity at 12 months, 18 months, and beyond. This stability might reflect an innate trait, but the feedback loop offers an alternative explanation. Once the cycle of curiosity and learning begins, it tends to perpetuate itself. The curious infant becomes the curious toddler becomes the curious child, not necessarily because curiosity is fixed but because early curiosity creates conditions that maintain and strengthen itself.

Understanding this feedback process raises questions about what determines initial curiosity levels. Genetics clearly plays some role, as twin studies show higher correlations in curiosity measures between identical twins than fraternal twins. But environmental factors also matter. Infants who experience responsive caregiving, where adults follow their gaze and engage with what interests them, show higher curiosity than those whose interests are ignored. The initial level of curiosity that starts the feedback loop appears to be shaped by both nature and nurture.

Curiosity and the Brain

Neuroscience research has begun to identify the brain systems involved in curiosity, providing a biological basis for the behavioral observations. Curiosity appears to involve the brain’s reward systems, particularly dopamine pathways that also drive other motivated behaviors like eating and social interaction. When we encounter something novel and potentially informative, these systems activate, creating a feeling of interest that motivates exploration and learning. In essence, our brains are wired to find information intrinsically rewarding.

This neurological perspective helps explain why curiosity is such a powerful driver of learning. Information seeking isn’t just instrumentally useful, helping us survive and navigate the world. It’s also directly pleasurable, at least for brains that are functioning normally. The curious infant staring at a novel object isn’t just building cognitive skills. They’re also experiencing something that feels good, a satisfaction that comes from encountering and processing new information.

Individual differences in these reward systems may partly explain individual differences in curiosity. Some people’s brains respond more strongly to novelty, generating more dopamine and more subjective interest when they encounter new things. These people would naturally seek out more novel experiences, engage more deeply with new information, and potentially develop stronger cognitive abilities as a result. The connection between curiosity and intelligence might trace back, ultimately, to differences in how powerfully our brains reward us for learning.

The brain research also reveals connections between curiosity and other cognitive processes. The same prefrontal regions that support curiosity also support working memory, attention control, and executive function. This suggests that curiosity isn’t a separate system but an integral part of the broader cognitive architecture. Highly curious individuals may have more developed prefrontal systems generally, explaining both their information-seeking behavior and their enhanced cognitive performance on various tasks.

What This Means for Nurturing Intelligence

The research on curiosity and intelligence has practical implications for parents, educators, and anyone concerned with cognitive development. If curiosity drives learning and intelligence, then fostering curiosity may be as important as providing information directly. This suggests a shift in emphasis from knowledge transmission to curiosity cultivation, from teaching children what to think to nurturing their desire to think at all.

Some approaches seem particularly promising based on the research. Following children’s interests rather than imposing adult agendas appears to strengthen curiosity by validating it and giving it opportunities to develop. Providing environments rich in novelty gives curiosity more to work with, more raw material for the information-seeking process. Modeling curiosity, letting children see adults genuinely interested in learning, may teach them that curiosity is valuable and appropriate at any age.

The research also raises cautions about practices that might suppress curiosity. Environments that emphasize rote learning over exploration, that punish questioning, or that provide so much structure that children have no opportunity for self-directed investigation might be undermining the very drive that powers cognitive development. Efficiency in knowledge transmission could come at the cost of curiosity, and thus at the cost of the self-sustaining learning that curiosity enables.

This connects to broader research on how animals maintain sophisticated cognitive abilities, including the role of curiosity and exploration in their development. Crows, for instance, are famously curious birds whose playful exploration of objects seems to support their remarkable problem-solving abilities. The parallel between avian and human curiosity suggests that the connection between exploration and intelligence may be a fundamental feature of how minds develop, regardless of the specific type of mind involved.

The Bigger Picture

The research on infant curiosity and intelligence challenges some common assumptions about cognitive development. Intelligence isn’t simply given, a fixed quantity that children are born with and carry through life. Nor is it simply learned, a product of instruction and practice that any child could acquire with sufficient exposure. Instead, intelligence appears to emerge from the interaction between initial dispositions and ongoing experience, with curiosity serving as a crucial bridge between the two.

This view has implications beyond individual children. Societies that value and nurture curiosity might develop more intelligent populations, not just because curious people learn more but because curiosity itself may be partly teachable and certainly can be supported or suppressed. Educational systems, cultural values, and even economic structures that affect how much time people have for exploration could all influence population-level cognitive development through their effects on curiosity.

The findings also connect to questions about what intelligence is for. If curiosity and intelligence co-evolved, selected together because curious organisms learned more and survived better, then intelligence wasn’t designed for taking tests or succeeding in school. It was designed for exploration, for the ongoing project of understanding and predicting a complex world. The sunk cost fallacy and other cognitive biases may represent the dark side of this system, mental shortcuts that usually serve exploration but sometimes lead us astray.

Perhaps the deepest implication is that intelligence isn’t a thing you have but a thing you do. The curious infant staring at a novel object isn’t demonstrating intelligence. They’re practicing it, building it, becoming more intelligent through the very act of seeking understanding. This suggests that maintaining curiosity throughout life might not just be pleasant but cognitively protective, a way of continuing to exercise the same information-seeking drive that built our minds in the first place.

For parents watching their babies stare intently at something new, the message is encouraging. That stare isn’t empty. It’s the visible surface of a profound cognitive process, the beginning of a lifelong journey of learning. The babies who look longest are telling us something about themselves, and about what intelligence really is: not a capacity to be filled but an appetite to be fed.