In 2006, researchers at the University of Washington did something unusual: they put on caveman masks and started harassing crows. They trapped and banded birds while wearing the masks, then released them. Years later, when someone wearing that same caveman mask walked through campus, crows would swoop and scold them aggressively. Crows who had never been captured but had watched the original trapping joined in. The grudge had spread. When the researchers walked through campus without masks, the same crows ignored them completely.

This wasn’t a fluke or a one-time study. Researchers have now documented that crows can remember specific human faces for at least five years, possibly longer. They recognize and react differently to people who have threatened them versus those who have fed them. They communicate this information to other crows. And they seem to teach their offspring: young crows who weren’t alive during the original incident will still mob someone wearing the threatening mask.

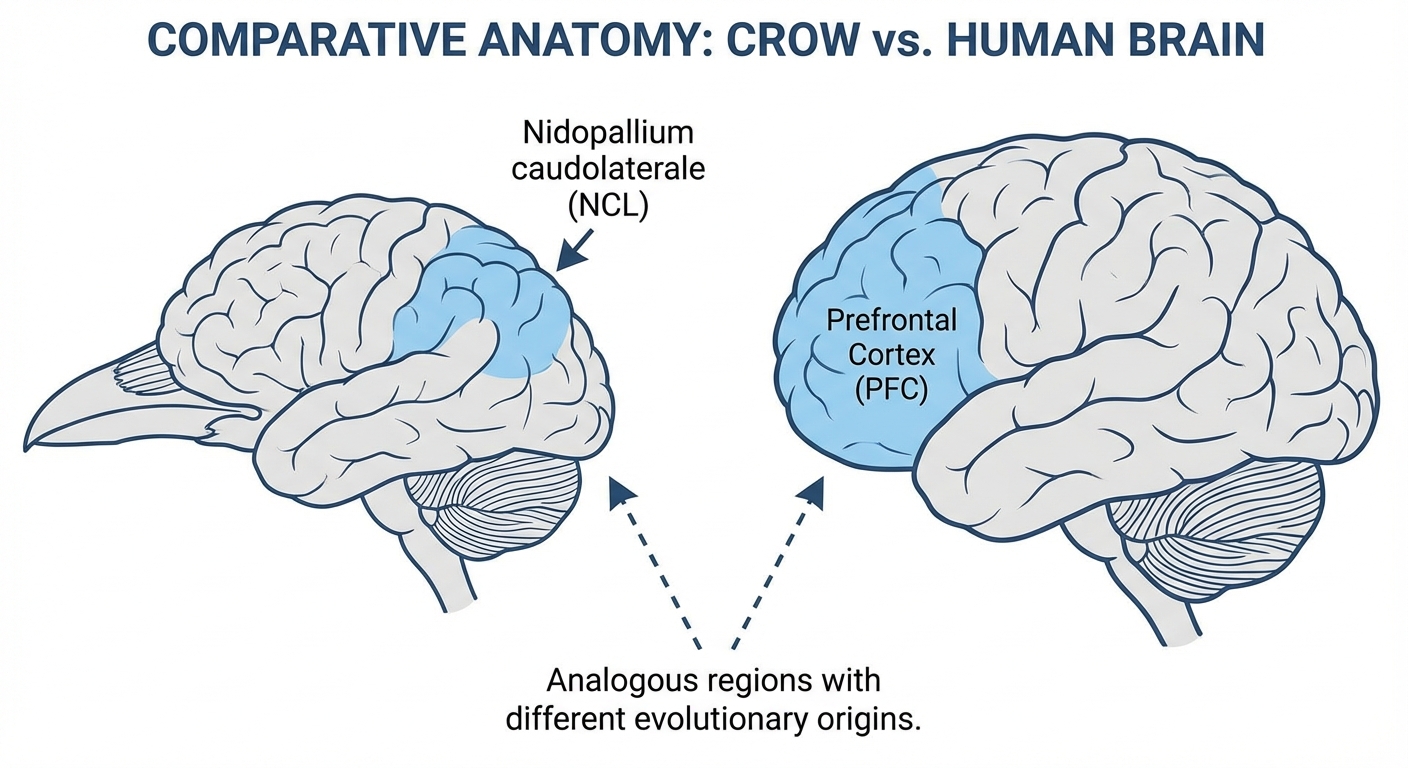

Crow intelligence forces a fundamental question: how did such sophisticated cognition evolve in an animal so different from us? The crow brain is the size of a walnut. They diverged from our common ancestor over 300 million years ago. They don’t even have a neocortex, the brain structure that supposedly makes human intelligence possible. Yet they use tools, solve puzzles, remember faces, hold grudges, and possibly mourn their dead. Understanding how crow minds work illuminates something profound about the nature of intelligence itself.

The Science of Crow Face Recognition

The face recognition studies were led by John Marzluff, a wildlife biologist who has spent decades studying corvid behavior. His team’s methodology was clever: by using masks, they could control exactly which “person” the crows associated with threat or kindness. Different researchers could wear the same mask on different days, eliminating the possibility that crows were recognizing gait, clothing, or other contextual cues.

The results were striking. Crows not only remembered the threatening face but their response intensified over time as the behavior spread through the population. In the first year after the original trapping, about 26% of crows encountered would scold the masked researcher. Five years later, that number had grown to about 66%. The grudge was becoming cultural knowledge.

Brain imaging studies revealed what happens neurologically when crows see a threatening face. Marzluff’s team injected crows with a radioactive glucose tracer, showed them either a threatening or neutral mask, then scanned their brains. When viewing the threatening face, crows showed activation in brain regions associated with fear, aggression, and memory consolidation. The pattern was remarkably similar to what you’d see in a mammalian brain processing threat, even though the underlying neural architecture is completely different.

How Corvids Stack Up Against Other Intelligent Animals

Crows belong to the corvid family, which includes ravens, jays, and magpies. This family has produced some of the most intelligent non-human animals on Earth, rivaling great apes, dolphins, and elephants in cognitive testing. The comparison is remarkable because these groups evolved their intelligence independently, along completely separate branches of the evolutionary tree.

The crow brain is structured differently from a mammalian brain, yet achieves similar cognitive outcomes. Mammals process complex thought in the neocortex, that wrinkled outer layer that expanded dramatically in primates and especially in humans. Birds don’t have a neocortex at all. Instead, corvids evolved dense clusters of neurons in a structure called the nidopallium caudolaterale, which performs many of the same functions. It’s an entirely different solution to the same problem, like how birds and bats both evolved flight but through completely different anatomical pathways.

New Caledonian crows manufacture tools from twigs and leaves, a behavior once thought unique to humans and a handful of great apes. They don’t just use found objects; they shape materials into hooks and probes to extract insects from tree bark. Even more impressively, they can solve multi-step problems requiring them to use one tool to obtain another tool to obtain food. This meta-tool use suggests they can plan ahead and understand causal relationships, not just follow instinct.

Ravens, the largest corvids, demonstrate what researchers call “theory of mind,” the ability to understand that other individuals have their own knowledge and intentions. Ravens will hide food, but if they notice another raven watching them cache it, they’ll return later to move the food to a new hiding spot. They seem to understand that the observer now knows where the food is and might steal it. This level of social cognition is rare in the animal kingdom.

The Evolutionary Puzzle of Bird Intelligence

Why are corvids so smart? Intelligence is metabolically expensive. The brain consumes enormous amounts of energy relative to its size, and for most animals, the cognitive benefits don’t justify the caloric costs. Something in corvid evolution made high intelligence worth the investment.

One leading hypothesis centers on their social complexity. Corvids live in intricate social groups with shifting alliances, hierarchies, and long-term relationships. Navigating this social landscape requires remembering who’s who, tracking relationships, anticipating others’ behavior, and planning social moves. This is the same pressure that may have driven primate intelligence, and it seems to have produced similar results in an entirely different lineage.

The other factor may be their generalist diet and lifestyle. Corvids are omnivores who exploit an enormous range of food sources, from carrion to insects to fruit to human garbage. They live across diverse habitats on every continent except Antarctica. This ecological flexibility may have favored cognitive flexibility, the ability to learn new solutions to new problems rather than relying on fixed instinctual responses.

The combination of social complexity and ecological flexibility may create a feedback loop. Smarter individuals navigate social and environmental challenges better, survive longer, and reproduce more. Their offspring inherit both genetic tendencies toward larger brains and cultural knowledge from their intelligent parents. Over millions of years, this ratcheting effect produces animals with remarkable cognitive abilities.

What Crow Grudges Tell Us About Memory

The persistence of crow grudges reveals something fascinating about how their memory works. These aren’t brief reactions that fade over days or weeks. Crows maintain stable, long-term memories of specific threatening individuals while presumably encountering thousands of human faces that they don’t bother to remember.

This selective memory makes evolutionary sense. Remembering which predators or threatening individuals to avoid is survival-critical information worth the neural resources to maintain. Remembering every neutral face encountered would be wasteful. Crow brains seem to have solved the same problem human memory solves: how to retain important information while discarding the trivial.

The social transmission of grudges adds another layer. Crows who never personally experienced the threat still learn to fear the threatening face by watching other crows’ reactions. This cultural learning allows information to spread faster than genetics ever could. A single crow’s bad experience can protect the entire local population, including future generations who weren’t yet alive during the original incident.

This mirrors how human cultural knowledge works. We don’t each have to learn from scratch that tigers are dangerous or that certain plants are poisonous. We inherit this knowledge socially, from parents and community, allowing us to benefit from the accumulated experience of previous generations. Crows, it seems, do something similar.

Do Crows Understand Death?

Among the most intriguing corvid behaviors are their responses to dead crows. When a crow discovers a dead member of its species, it often calls loudly, attracting other crows to the scene. The gathered crows will stand near the body, sometimes for extended periods, engaging in what researchers carefully call “apparent cacophonous aggregations around dead conspecifics,” but which looks remarkably like a funeral.

What are they doing? The scientific interpretation is that crows are gathering information about potential threats. If a crow died here, something dangerous might be nearby. By investigating the body and the surrounding area, crows can learn whether a predator, a window, a power line, or some other hazard is present. The loud calling may alert other crows to both the danger and the information-gathering opportunity.

But some researchers suspect there’s more to it. Crows often stay near the body longer than would be necessary for threat assessment. They sometimes touch the body. They occasionally bring objects and leave them near the dead crow. Whether this represents mourning in any human sense remains scientifically uncertain, but the behavior is complex enough that researchers are hesitant to dismiss emotional components entirely.

The Bigger Picture

Crow intelligence matters beyond its intrinsic fascination because it challenges assumptions about what minds require. For decades, scientists assumed sophisticated cognition required the neocortex, that big brains meant big intelligence, and that human-like thinking emerged from human-like brain structures. Corvids suggest these assumptions are wrong.

Intelligence appears to be a pattern that evolution can produce through multiple pathways. The specific neural architecture matters less than the computational capacity it enables. Corvids evolved dense neural clusters that perform functions analogous to our neocortex, solving the same problems through different biological means. This is convergent evolution at the level of cognition, different lineages arriving at similar capabilities through independent paths.

This has implications for how we think about intelligence elsewhere in the animal kingdom, and potentially beyond Earth. If intelligence can evolve so differently even on this planet, we shouldn’t assume that alien minds, if they exist, would work anything like ours. The space of possible minds may be far larger than our single example would suggest.

Understanding crow cognition also raises ethical questions. If crows remember, hold grudges, learn culturally, use tools, and possibly experience something like grief, how should we treat them? These aren’t questions science alone can answer, but science can inform them. The more we learn about the richness of corvid mental life, the harder it becomes to dismiss them as mere animals operating on instinct.

Next time a crow watches you from a power line, consider that it may genuinely be watching you, processing your face, evaluating whether you’re a threat or a potential source of food, and potentially remembering you years later. The world is full of minds paying attention in ways we’re only beginning to understand.