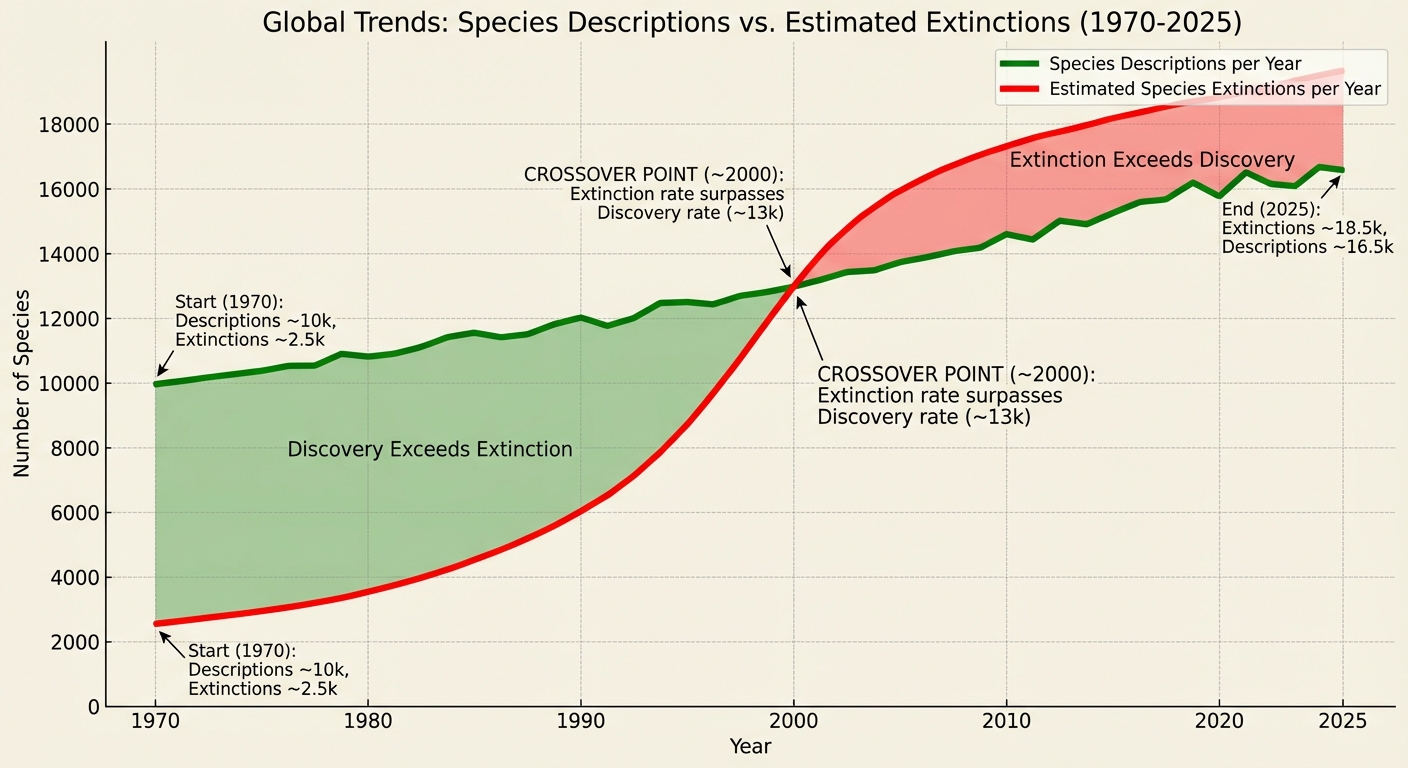

In 2025, scientists described approximately 16,500 species that had never been formally named or documented before. That’s roughly 45 new species every single day: fish from remote rivers, insects from tropical canopies, fungi from forest soils, plants from mountainsides, and countless microorganisms from environments previously unsampled. The pace of discovery has actually accelerated over the past decade, making this period, paradoxically, the golden age of species discovery even as we also live through the sixth mass extinction.

This seems contradictory. How can we be finding more species than ever while species are disappearing at rates not seen since the dinosaurs vanished? The answer reveals something important about both the natural world and human knowledge. We’re racing to document biodiversity even as it disappears, using technologies that let us see what was previously invisible, motivated by urgency that previous generations didn’t feel. The flood of new species represents scientific progress, but it also represents a desperate catalog of what we might lose.

Understanding the species discovery boom requires examining three interrelated phenomena: the technologies enabling discovery, the ecosystems yielding new species, and the scientists working to describe them before it’s too late. Together, these factors have created an unprecedented moment in the history of taxonomy, the science of naming and classifying life.

The Technology Revolution in Species Discovery

For most of the history of biology, discovering a new species meant physically collecting a specimen, examining its morphology under a microscope, comparing it to known species in museum collections, and publishing a formal description in a scientific journal. This process was slow, requiring specialized expertise and access to reference collections housed in institutions scattered across the world. A taxonomist studying beetles might spend years visiting museums to compare specimens before confidently declaring a find was genuinely new.

DNA barcoding transformed this process. By sequencing a standardized gene region, researchers can quickly determine whether a specimen matches any known species in genetic databases. If the sequence diverges significantly from everything on record, it’s almost certainly undescribed. This doesn’t replace traditional taxonomy, which still requires detailed morphological description, but it dramatically accelerates the initial discovery phase. A researcher can process hundreds of samples in the time it once took to examine a few dozen.

The technology has also become dramatically cheaper and more portable. Early DNA sequencing required sophisticated laboratories; now hand-held devices can sequence DNA in the field. Researchers working in remote locations can identify species within hours of collection, adjusting their sampling strategy based on what they find. This enables more targeted exploration, focusing effort on areas and taxa most likely to yield new discoveries.

Artificial intelligence has added another layer of capability. Machine learning algorithms can now identify species from photographs, sounds, and even environmental DNA, genetic material shed by organisms into water or soil. Cameras and microphones deployed across landscapes continuously gather data that AI systems analyze, flagging unusual observations for expert review. This multiplies the effective reach of researchers, allowing a small number of taxonomists to monitor vast areas.

The combination of these technologies has revealed how much we were missing with traditional methods. When researchers systematically survey an ecosystem using modern tools, they typically find that a significant fraction of species present were previously unknown to science. In tropical forests and deep-sea environments, that fraction can exceed half. We weren’t finding new species because we weren’t equipped to look properly.

Where the New Species Are Coming From

The distribution of new species discoveries reveals patterns in our knowledge gaps. Tropical rainforests, particularly in the Amazon, Congo Basin, and Southeast Asia, contribute enormous numbers of new insects, plants, and fungi. These ecosystems harbor the majority of terrestrial biodiversity, yet have been the least thoroughly surveyed. When researchers set up malaise traps or fog tree canopies with insecticide to collect arthropods, they routinely find species never seen before.

The deep ocean is another frontier. The deep sea remains darker and less explored than space, and every submersible dive brings back organisms new to science. Chemosynthetic ecosystems around hydrothermal vents host unique communities adapted to extreme conditions. Cold seeps, whale falls, and the vast abyssal plains all contain species found nowhere else. Only about 5 percent of the ocean floor has been explored in detail, suggesting discoveries will continue for decades.

Perhaps surprisingly, new species also emerge from regions thought well-documented. Museum collections contain unprocessed specimens that genetic analysis reveals to be distinct species, misidentified or lumped together by earlier taxonomists. Cryptic species, organisms that look identical but are genetically and reproductively distinct, turn up regularly when researchers apply molecular tools to familiar groups. What appeared to be one widespread species sometimes proves to be several localized species, each with its own conservation needs.

Caves, islands, and mountain peaks, isolated ecosystems where evolution proceeds independently, continue yielding discoveries. A cave in Vietnam might harbor blind fish and invertebrates found nowhere else. A newly surveyed Indonesian island might have its own species of tree kangaroo. A mountain range in South America might shelter plants that evolved in isolation for millions of years. These ecosystems are small but packed with endemic species that haven’t dispersed elsewhere.

Even urban and agricultural landscapes occasionally produce surprises. A new species of ant might be living in city parks, overlooked because no one thought to look. Fungi associated with crop plants may have been present all along but never formally described. The familiar world still contains undocumented diversity, though at lower densities than wildlands.

The Race Against Extinction

The accelerating pace of discovery is driven partly by technology, partly by funding, but also by a growing sense of urgency. Scientists know that many species will go extinct before they’re ever named. The destruction of tropical forests, pollution of waterways, and warming of oceans are eliminating species faster than taxonomists can describe them. This creates pressure to document what exists before it’s gone, even if detailed study must come later.

The concept of “dark extinction” captures this reality: species disappearing without ever having been recognized by science. We can estimate that thousands of species have gone extinct in recent decades that we never knew existed. They lived their evolutionary lives, occupied ecological niches, interacted with other organisms, and then vanished without a name, a description, or a preserved specimen. We know they existed only statistically, by what’s missing from our models of biodiversity.

This urgency has reshaped the field of taxonomy. Rapid descriptions that would once have been considered incomplete are now sometimes accepted as better than no description at all. Consortiums of researchers collaborate to process backlogs of collected specimens. DNA barcoding projects aim to sequence as much of life as possible before it disappears. The ambition has shifted from leisurely documentation to emergency inventory.

Citizen science has become essential to this effort. Platforms like iNaturalist allow millions of amateur naturalists to photograph organisms and contribute observations to databases that researchers mine for discoveries. A hiker in Costa Rica might photograph an unusual plant that experts later confirm as undescribed. A diver in the Philippines might capture images of fish that turn out to be new species. The distributed attention of enthusiastic amateurs spots things professionals would miss.

Like the fungal networks that allow trees to share information underground, these citizen science networks create a kind of collective sensing system for biodiversity. Individual observations flow into central databases, where patterns emerge. An unusual moth photographed across multiple locations might prompt investigation, revealing a species hiding in plain sight. Technology enables coordination that makes the collective more powerful than any individual researcher.

What Discovery Reveals About Ignorance

Perhaps the most striking implication of the species discovery boom is what it reveals about the limits of current knowledge. If we’re still finding 16,000 species per year, how many remain undiscovered? Estimates vary wildly, from 8 million to over 100 million total species on Earth. We’ve described roughly 2 million so far. Even conservative estimates suggest we’ve cataloged less than a quarter of life on the planet.

The unknown unknowns are concentrated in particular groups. Large mammals are well documented; nearly every species has been described. But insects, which comprise the majority of animal species, remain vastly undersampled. Fungi are even more mysterious; we may have described only 5 to 10 percent of fungal species. Bacteria and archaea, the most ancient and numerous forms of life, are mostly known only from genetic sequences, with less than 1 percent having been isolated and cultured for detailed study.

This ignorance has practical consequences. We can’t protect what we don’t know exists. Conservation plans based on incomplete species lists may miss critical components of ecosystems. Pharmaceutical discoveries often come from organisms previously unknown; species going extinct before they’re discovered take their chemical secrets with them. The library of life is burning while we’ve barely cataloged its contents.

Yet there’s also something exhilarating about so much remaining to discover. The natural world still holds surprises. In an age when much of science involves incremental advances on known phenomena, taxonomy offers the thrill of genuine novelty: this creature has never been seen by human eyes, never had a name, never been placed in the tree of life. Each new species is a small expansion of human knowledge, a reminder that the world is bigger and stranger than we imagined.

The Bigger Picture

The golden age of species discovery exposes a fundamental tension in humanity’s relationship with the natural world. We’re simultaneously more capable of understanding biodiversity and more responsible for its destruction than any generation before us. The same technologies enabling discovery, genetic sequencing, AI, global communications, are products of an industrial civilization that’s driving extinctions. We’re racing to document what our way of life is eliminating.

This isn’t merely tragic; it’s also instructive. The pace of discovery suggests that our past estimates of biodiversity were too low. That means past estimates of extinction rates may also have been too low; we can’t lose what we didn’t know existed, but the losses are real regardless. The numbers paint a picture of a natural world far richer than we knew and far more imperiled than we admitted.

There’s also a lesson about scientific humility. Taxonomy is one of the oldest sciences, practiced systematically for over 250 years since Linnaeus established the modern naming system. Yet we’ve barely scratched the surface of life’s diversity. If something as fundamental as “how many species exist?” remains uncertain by a factor of ten, how confident should we be about more complex ecological questions? The unknown species represent unknown relationships, unknown interactions, unknown possibilities.

The discovery boom will eventually slow. As remote areas become accessible and technologies mature, the rate of new findings will decline. Eventually, taxonomy will transition from inventory mode to refinement mode, correcting errors and adding detail rather than finding fundamentally new things. But that transition is decades away. For now, we live in a remarkable moment when Earth’s biodiversity is both being revealed and being erased, when scientists can discover 45 species a day and know that others are vanishing unrecorded.

Somewhere in a tropical forest tonight, an insect is flying that has never been named. In the deep ocean, a fish is swimming that no human has ever seen. In soil beneath our feet, fungi are growing that remain unknown to science. The world is full of undiscovered life. The question is how much will still be there when we finally get around to looking.