You brush your teeth to prevent cavities and keep your breath fresh. What you probably don’t consider, as you scrub your molars each morning, is that you’re also performing a kind of neurological hygiene. Research published in early 2026 has added striking new evidence to a hypothesis that once seemed absurd: the bacteria living in your mouth may be contributing to brain diseases, including Parkinson’s, through a circuitous route that passes through your gut.

The bacterium at the center of this story is Streptococcus mutans, perhaps the most familiar villain in dentistry. It’s the primary cause of tooth decay, converting sugars into acids that erode enamel. Nearly everyone harbors S. mutans in their mouth, usually in manageable quantities kept in check by good hygiene and a balanced oral microbiome. But scientists at several research institutions have now demonstrated that when these bacteria migrate to the gut, they can produce metabolites that enter the bloodstream, cross the blood-brain barrier, and damage the very neurons that die in Parkinson’s disease.

This isn’t a fringe theory or a preliminary finding. It represents the convergence of multiple research threads that have been developing for over a decade: the gut-brain axis, the role of inflammation in neurodegeneration, and the systemic effects of oral health. Understanding how a mouth bacterium might contribute to brain disease requires following a trail that winds through three distinct organ systems and challenges assumptions about where diseases actually begin.

The Gut-Brain Axis: A Two-Way Street

The connection between the gut and the brain is far more extensive than most people realize. The enteric nervous system, sometimes called the “second brain,” contains roughly 500 million neurons lining the gastrointestinal tract. This network operates semi-independently, coordinating digestion without requiring conscious input, but it communicates constantly with the central nervous system through the vagus nerve, a superhighway of neural signals running from the brainstem to the abdomen.

This bidirectional communication means that conditions in the gut can influence brain function and vice versa. Stress, for instance, doesn’t just make you feel nauseated emotionally; it literally alters gut motility, immune function, and the composition of the microbiome. Conversely, the trillions of microorganisms living in your intestines produce neurotransmitters, modulate inflammation, and generate metabolites that reach the brain. An estimated 90 percent of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut, not the brain.

The implications for neurological disease became apparent as researchers noticed patterns they couldn’t explain otherwise. Parkinson’s patients often report gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly constipation, years or even decades before motor symptoms appear. Some scientists proposed that Parkinson’s might actually begin in the gut, with pathological proteins gradually spreading upward to the brain via the vagus nerve. Studies in animals supported this hypothesis: when researchers injected misfolded alpha-synuclein (the protein that clumps abnormally in Parkinson’s) into mouse intestines, it eventually appeared in their brains.

But the gut-brain axis isn’t just about neurons. The bloodstream carries molecules from the intestines to every organ in the body, including the brain. When gut bacteria produce certain metabolites, those compounds can enter circulation, potentially crossing the blood-brain barrier if they’re small enough or if the barrier has been compromised by inflammation. This chemical communication adds another pathway through which the gut microbiome might influence neurological health.

From Mouth to Gut: How Oral Bacteria Make the Journey

Your mouth contains one of the most diverse microbial ecosystems in your body, home to over 700 species of bacteria, plus fungi, viruses, and archaea. Most of these organisms are harmless or even beneficial, but some are problematic when they escape their usual ecological niche. Streptococcus mutans is well adapted to life on tooth surfaces, where it forms biofilms (dental plaque) and produces lactic acid as it ferments sugars. This acid production is what makes it so destructive to enamel.

But S. mutans doesn’t stay in the mouth. Every time you swallow, you send saliva containing millions of bacteria down to your stomach. Most oral bacteria can’t survive the acidic environment there, but some species are hardier than others. Studies have found viable oral bacteria, including S. mutans, in the intestines of people with poor oral hygiene, gum disease, or compromised immune systems. The bacteria can establish colonies in the gut, where they encounter a very different environment than their native oral habitat.

The journey from mouth to gut isn’t the only way oral bacteria spread systemically. Gum disease (periodontitis) allows bacteria direct access to the bloodstream through inflamed, bleeding gum tissue. This is why dentists warn patients with certain heart conditions to take antibiotics before dental procedures; oral bacteria entering the blood can colonize damaged heart valves. Researchers have found oral bacteria in atherosclerotic plaques, in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, and in numerous other locations far from the mouth.

What makes the recent Parkinson’s research noteworthy is the specific mechanism proposed. The researchers didn’t just find correlations between oral health and Parkinson’s risk; they identified a plausible causal chain. When S. mutans colonizes the gut, it produces certain metabolites that aren’t generated in the mouth. These compounds, once absorbed into the bloodstream, can cross into the brain and appear to be toxic to dopaminergic neurons, the specific cell population that degenerates in Parkinson’s disease.

The Mechanism: Metabolites, Inflammation, and Neuronal Damage

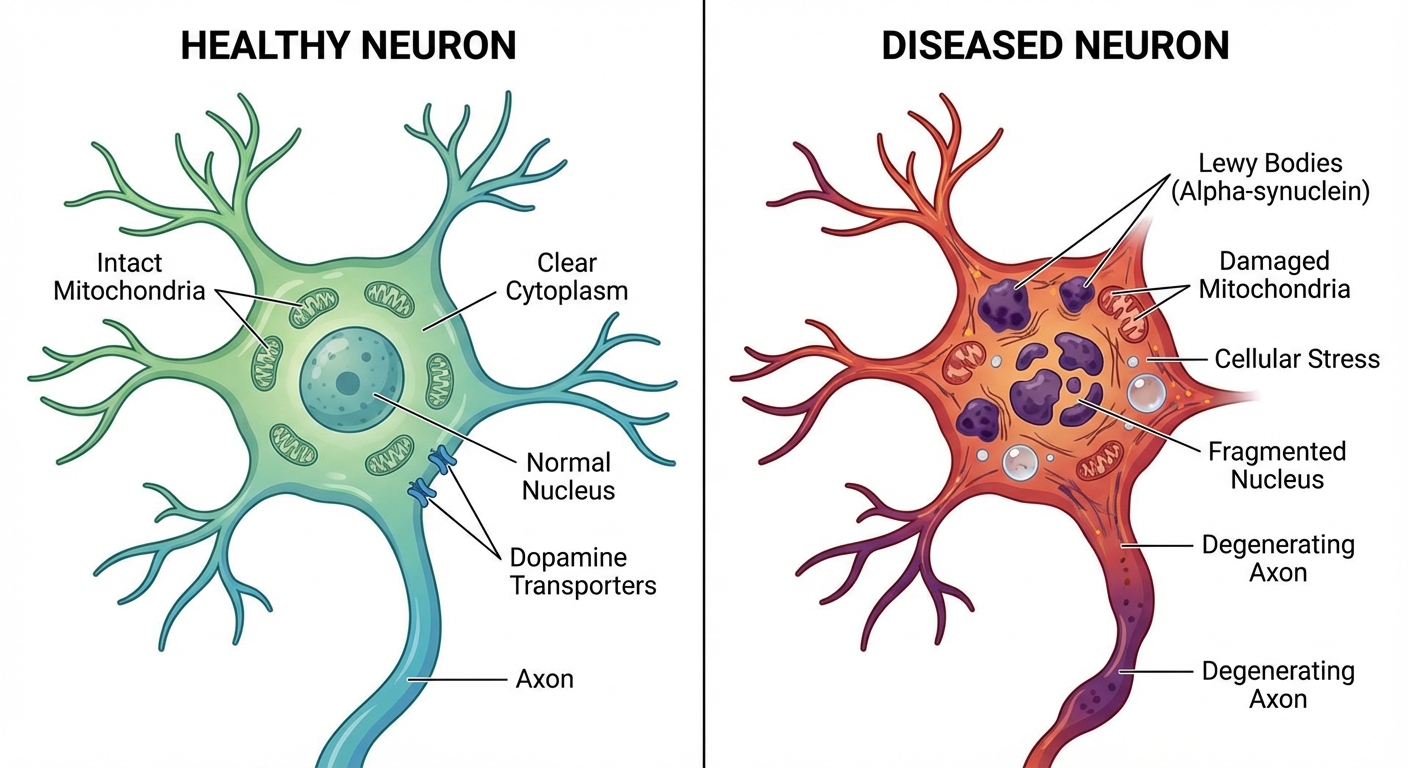

Understanding how a bacterial metabolite might damage neurons requires a brief detour into the pathology of Parkinson’s disease. The motor symptoms of Parkinson’s, including tremor, rigidity, and slowness of movement, result from the death of dopamine-producing neurons in a brain region called the substantia nigra. By the time symptoms appear, patients have typically lost 60 to 80 percent of these neurons. The question that has driven decades of research is: what kills these cells?

Multiple factors appear to contribute, including genetics, environmental toxins, and aging itself. But a common thread in many cases is the accumulation of misfolded alpha-synuclein, which forms clumps called Lewy bodies inside neurons. These aggregates are toxic, interfering with cellular function and eventually triggering cell death. What causes alpha-synuclein to misfold in the first place remains partially mysterious, but inflammation and oxidative stress are known contributors.

This is where the oral bacteria hypothesis gains traction. The metabolites produced by gut-colonizing S. mutans appear to trigger inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in neural tissue. In laboratory studies, exposure to these compounds caused alpha-synuclein to misfold at higher rates and damaged mitochondria in dopaminergic neurons. Mitochondrial dysfunction is another hallmark of Parkinson’s pathology; these cellular powerhouses are particularly vulnerable in dopamine-producing cells, which have high energy demands.

The research team demonstrated that mice colonized with S. mutans in their guts (but not their mouths) showed progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons and motor symptoms resembling Parkinson’s. When the researchers administered antibiotics that eliminated the gut bacteria, the neurodegeneration slowed. Importantly, not all strains of S. mutans produced the same effects; some variants were more pathogenic than others, suggesting that specific bacterial genetics matter.

Human evidence, while less definitive than controlled animal experiments, points in the same direction. Epidemiological studies have consistently found that people with periodontal disease have elevated Parkinson’s risk. A 2024 meta-analysis combining data from over 300,000 participants calculated that severe gum disease was associated with roughly 1.5 times the odds of developing Parkinson’s compared to good oral health. The new research helps explain why this correlation might reflect causation.

Historical Context: From Focal Infection to the Microbiome Era

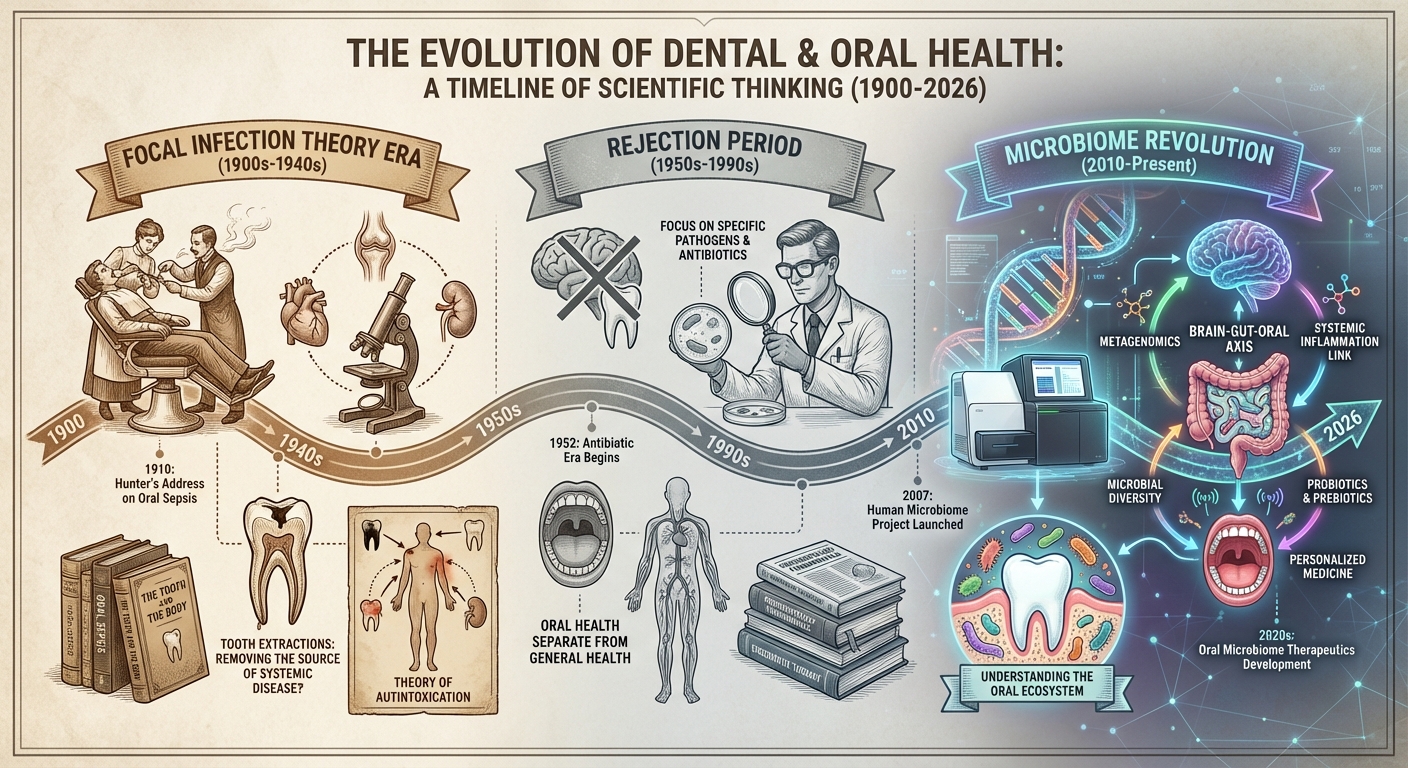

The idea that oral infections could cause systemic disease isn’t new; it’s actually a very old theory that fell out of favor before being partially rehabilitated. In the early twentieth century, the “focal infection theory” held that infections in the teeth, tonsils, and sinuses could spread through the body and cause diverse diseases, from arthritis to mental illness. This theory led to aggressive extraction of teeth and removal of tonsils based on minimal evidence.

By mid-century, the focal infection theory had been thoroughly debunked. Controlled studies showed that removing supposedly infected teeth didn’t cure the diseases they were blamed for. The medical profession swung to the opposite extreme, dismissing connections between oral health and systemic disease as essentially superstitious. For decades, dentistry and medicine operated in separate silos, treating the mouth as somehow disconnected from the rest of the body.

The microbiome revolution, which began in earnest around 2010 with advances in DNA sequencing technology, forced a reconsideration. Researchers discovered that the bacterial ecosystems inhabiting various body sites were far more complex and consequential than previously imagined. The gut microbiome in particular emerged as a major player in health and disease, influencing metabolism, immunity, and even behavior. As scientists mapped microbial populations throughout the body, they found extensive overlap and traffic between sites.

The current understanding represents neither a return to the old focal infection theory nor its total rejection. We now know that oral bacteria can cause systemic effects, but through specific, demonstrable mechanisms rather than vague “toxins.” The mouth-gut-brain connection in Parkinson’s exemplifies this more sophisticated understanding: a specific bacterium, traveling a specific route, producing specific compounds, damaging specific cell populations. This level of mechanistic detail was impossible in the early twentieth century.

What This Means for Prevention and Treatment

If oral bacteria genuinely contribute to Parkinson’s disease, the implications for prevention are significant. Unlike many Parkinson’s risk factors, oral health is largely modifiable. Regular brushing, flossing, and dental care reduce S. mutans populations and prevent periodontal disease. These are inexpensive, safe interventions that most people should be doing anyway. If they also reduce neurodegeneration risk, the case for good oral hygiene becomes even stronger.

However, scientists urge caution about drawing premature conclusions. The research, while compelling, remains preliminary. Animal models don’t always translate to humans. Epidemiological associations can reflect confounding factors rather than causation. And even if the oral-gut-brain connection proves real, it likely represents one contributing factor among many rather than a singular cause of Parkinson’s. The disease probably results from multiple hits accumulating over decades, with genetics, environment, and lifestyle all playing roles.

Clinical trials are now being planned to test whether aggressive treatment of periodontal disease or targeted antibiotics against gut S. mutans might slow Parkinson’s progression in people already diagnosed. These studies will take years to complete, and their results aren’t guaranteed. In the meantime, neurologists aren’t recommending any dramatic changes to treatment protocols based on this research.

What the findings do suggest is a broader reconceptualization of neurodegenerative disease. For too long, diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s were studied almost exclusively as brain problems. The emerging picture is more systemic: the brain sits at the end of influence cascades that begin in the gut, the mouth, even the immune system. Just as recommendation algorithms work by aggregating signals from many sources, neurodegenerative disease may result from the convergence of many risk factors, some of which originate surprisingly far from the brain itself.

The Bigger Picture

The oral bacteria-Parkinson’s connection illustrates something important about how diseases actually work. We tend to think of conditions as having single causes: a virus causes an infection, a gene causes a genetic disorder, a toxin causes poisoning. But chronic diseases, especially those of aging, rarely follow such simple logic. They emerge from complex interactions among genetics, environment, behavior, and chance, playing out across decades and multiple organ systems.

This complexity is daunting for researchers trying to find cures, but it’s actually encouraging for prevention. If Parkinson’s has many contributing factors, then reducing any one of them might matter. You can’t change your genes, but you can brush your teeth. You can’t reverse decades of accumulated damage, but you might slow further accumulation by addressing modifiable risks.

The research also highlights how much we still don’t know about the microbes that share our bodies. The human microbiome contains trillions of organisms, most of which have never been studied in detail. We’re only beginning to understand their metabolic capabilities and their effects on human physiology. Much like the fungal networks that allow trees to communicate underground, the bacterial communities in our bodies form ecosystems with properties that exceed the sum of their parts. What other connections remain to be discovered?

Finally, the mouth-to-brain story underscores why medicine should resist artificial boundaries between specialties. The mouth isn’t separate from the body. The gut isn’t separate from the brain. The immune system influences everything. Dental disease affects cardiovascular health, mental health, and now possibly neurological health. The researchers who made this discovery did so by ignoring disciplinary boundaries and following the evidence wherever it led.

When you brush your teeth tonight, you might think about the neurons in your substantia nigra, those irreplaceable cells whose slow death causes some of the most devastating symptoms of an already difficult disease. The connection between your toothbrush and those neurons isn’t direct or certain, but it’s real enough to take seriously. Sometimes the most important medical interventions are the ones we’ve been doing all along, for reasons we didn’t fully understand.