In January 2026, D-Wave Quantum Inc. announced something that quantum computing experts had been calling impossible for years: they had figured out how to control thousands of qubits without drowning the system in a spaghetti mess of wiring. The same week, researchers published a new error correction method that barely slows down as you add more qubits. A month earlier, Google demonstrated that quantum systems can actually become more stable as they scale, not more fragile. Each of these achievements had been written off as theoretical at best, pipe dream at worst. And yet here we are.

The pattern is impossible to ignore. Quantum computing doesn’t just advance; it keeps doing things that the field’s own experts declared unfeasible. Understanding why reveals something fundamental about both the technology and the nature of scientific progress itself.

The Wiring Problem That Couldn’t Be Solved

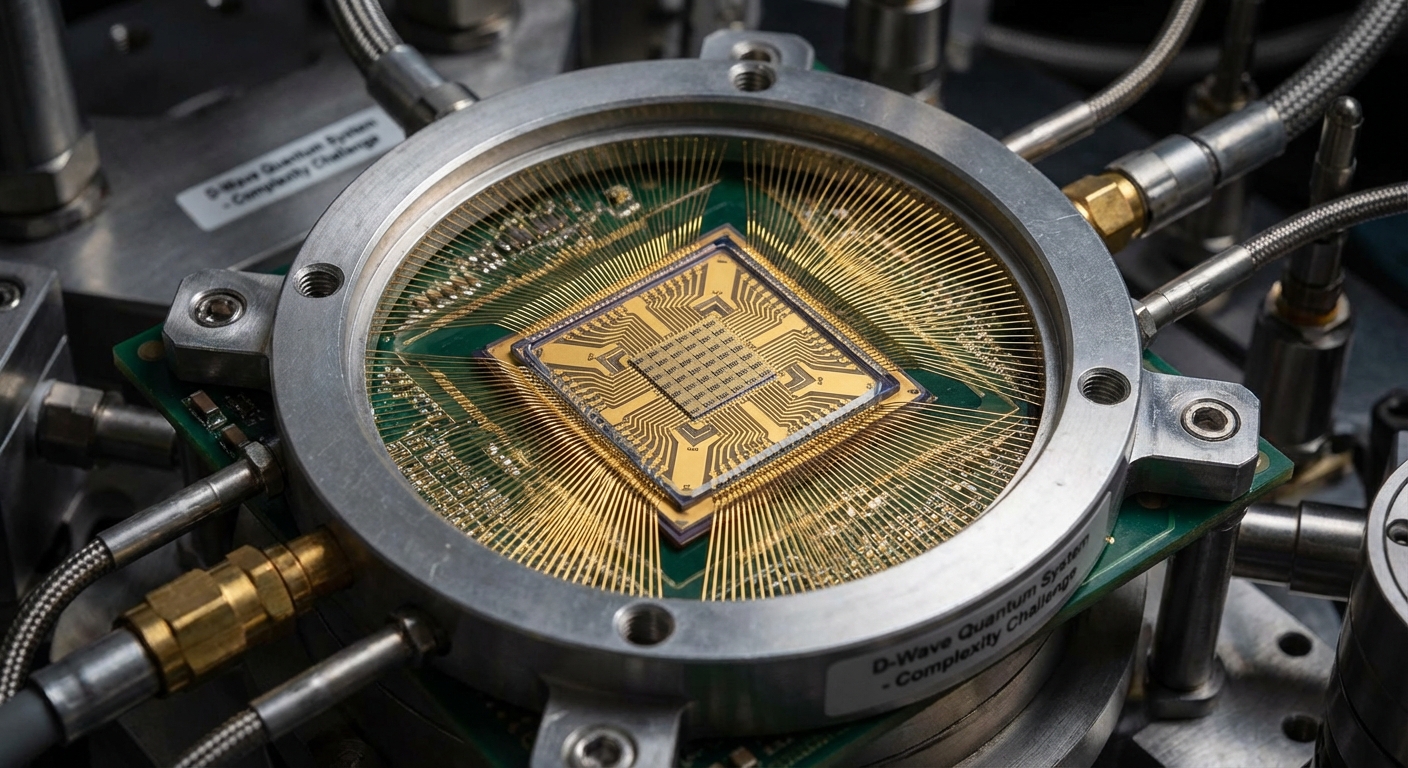

The challenge D-Wave tackled sounds almost mundane: wiring. Every qubit in a quantum computer needs to be individually controlled, and that control requires physical connections. As you add more qubits, you add more wires. At some point, the physics simply stops cooperating. The wires generate heat. They take up space. They interfere with each other. Building a quantum computer with millions of qubits using conventional approaches would require a cooling system the size of a building and more control wires than could physically fit.

For years, the consensus held that this was an engineering problem without an engineering solution. You could make qubits better. You could make them more stable. But the wiring problem was fundamental. You couldn’t escape the tyranny of one wire per qubit, and that meant quantum computers would never scale to truly useful sizes.

D-Wave’s breakthrough came from refusing to accept this constraint. Using multiplexed digital-to-analog converters, their team demonstrated control of tens of thousands of qubits with just 200 bias wires. They achieved this by integrating a high-coherence fluxonium qubit chip with a multilayer control chip using superconducting bump bonding. Key components were fabricated at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The technical details matter less than the conceptual shift. D-Wave didn’t solve the wiring problem by making better wires. They solved it by changing what “controlling a qubit” means at the hardware level. The approach that everyone knew couldn’t work turned out to be the wrong approach entirely.

When Errors Fix Themselves

Quantum computers make mistakes. This isn’t a bug in the design; it’s a fundamental feature of working with quantum states. Qubits exist in superposition, meaning they hold multiple values simultaneously until measured. But that delicate quantum state can collapse, or “decohere,” when it interacts with its environment. Heat, electromagnetic radiation, even vibrations can introduce errors.

The standard approach to this problem borrows from classical computing: error correction codes. You spread information across multiple physical qubits to create logical qubits that can detect and fix errors. The catch is that error correction itself requires computation, and that computation takes time. As you scale up the number of qubits, the error correction overhead was supposed to scale up too, potentially faster than the useful computation you were trying to protect.

Researchers at multiple institutions have now demonstrated that this scaling curse can be broken. A team published results in early January 2026 showing error correction where “the time needed for error-correction computation barely increases even as the number of components grows.” They achieved both “ultimate accuracy” and “ultra-fast computational efficiency” simultaneously, which the field had long assumed required tradeoffs.

IBM contributed to this progress by achieving efficient quantum error correction decoding with a ten-times speedup over the previous leading approach, completed a full year ahead of their roadmap. Their system can decode errors in real-time, in less than 480 nanoseconds, using what are called quantum low-density parity-check codes.

The significance here isn’t just faster error correction. It’s that the problem of error correction overhead, which had seemed like a fundamental limit on quantum computing’s usefulness, turned out to be a problem of approach rather than physics. The universe wasn’t forbidding large-scale quantum computation. Our methods were just inefficient.

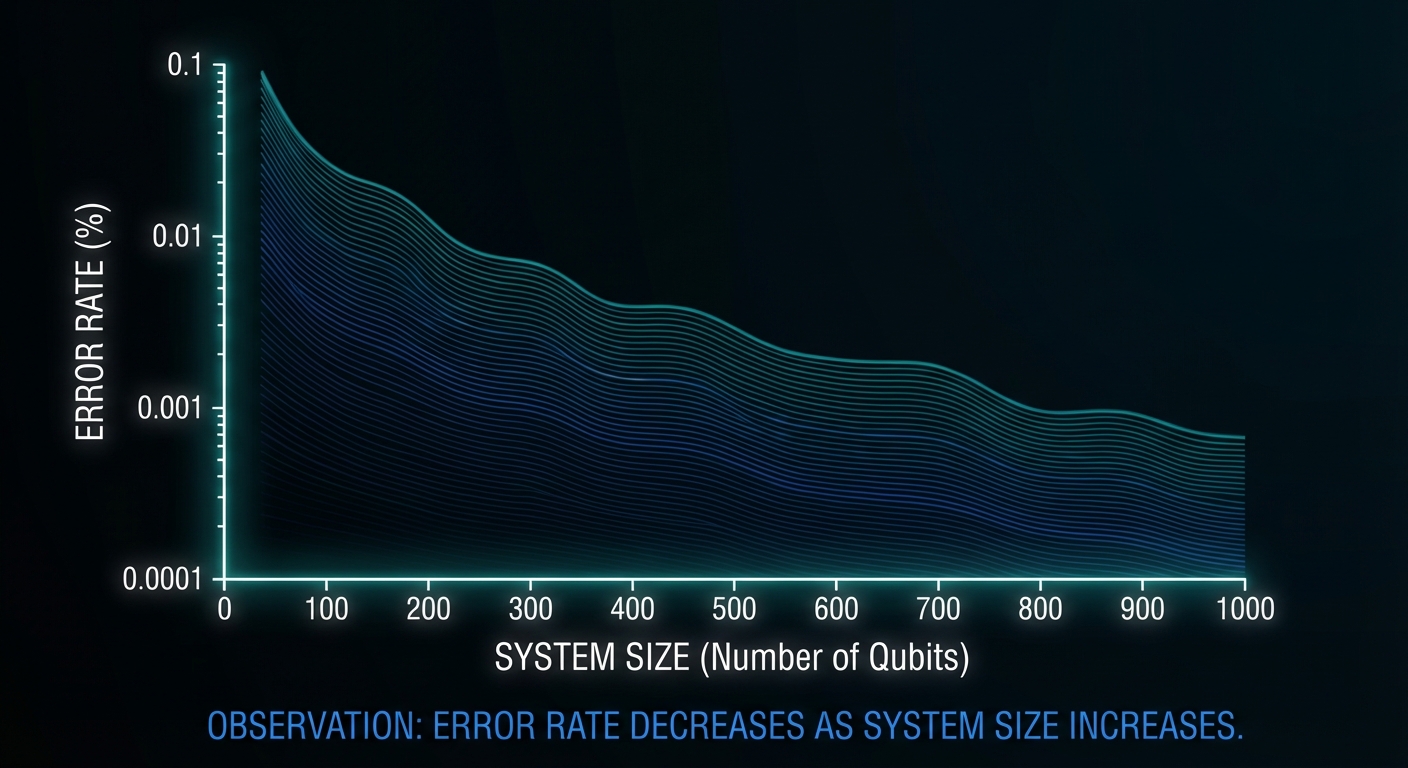

Google’s Paradox: Bigger Is Better

Perhaps the most counterintuitive breakthrough came from Google DeepMind’s AlphaQubit system. In classical engineering, larger systems are generally harder to control and more prone to failure. A car with more parts has more potential points of breakdown. A longer supply chain has more potential disruptions. Scale introduces fragility.

Quantum systems were assumed to follow this pattern even more severely. Quantum states are delicate. More qubits should mean more opportunities for decoherence, more chances for errors to cascade, more ways for the system to collapse into uselessness. Building bigger quantum computers should make the stability problem worse, not better.

Google demonstrated the opposite. Their quantum system actually becomes more stable as it scales. With each step up in the “distance” of the error-correcting code (from distance 3 to 5 to 7), the logical error rate dropped exponentially, showing a scaling factor of 2.14x. AlphaQubit achieved a 30% reduction in errors compared to the best traditional algorithmic decoders.

This result marks what researchers call the end of the “Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum” (NISQ) era. For years, quantum computers existed in a twilight zone: too noisy for reliable computation but too interesting to abandon. The assumption was that we’d need revolutionary new approaches to escape NISQ and reach fault-tolerant quantum computing. Instead, incremental improvements in error correction crossed a threshold that changed the fundamental scaling behavior.

Why Experts Keep Being Wrong

The pattern of quantum computing breakthroughs contradicting expert predictions isn’t random. It reflects something systematic about how we reason about new technologies, especially technologies that operate according to different rules than our everyday experience.

Human intuition evolved in a classical world. We understand that things can be in one place or another, not both. We know that observing something doesn’t change it. We expect larger systems to be harder to manage. Quantum mechanics violates all of these intuitions. Superposition lets quantum states be multiple things at once. Measurement fundamentally alters quantum systems. And entanglement creates correlations that have no classical analogue.

When experts predict what’s possible in quantum computing, they’re often reasoning by analogy to classical systems. The wiring problem seemed insurmountable because in classical computing, you really do need individual connections to individual components. The error correction overhead seemed fundamental because in classical error correction, there really are tradeoffs between accuracy and speed. The fragility of large quantum systems seemed obvious because large classical systems really are harder to control.

Each of these predictions was reasonable given classical assumptions. Each turned out to be wrong because quantum systems don’t follow classical rules. The breakthroughs came from researchers who found ways to exploit quantum weirdness rather than fight it.

This suggests that expert consensus about quantum computing limits should be treated with particular skepticism. Not because the experts are incompetent, but because the very expertise that makes someone good at reasoning about classical systems can become a liability when reasoning about quantum ones. The “impossible” things often turn out to be merely “impossible if you think about it the wrong way.”

The Road to Quantum Advantage

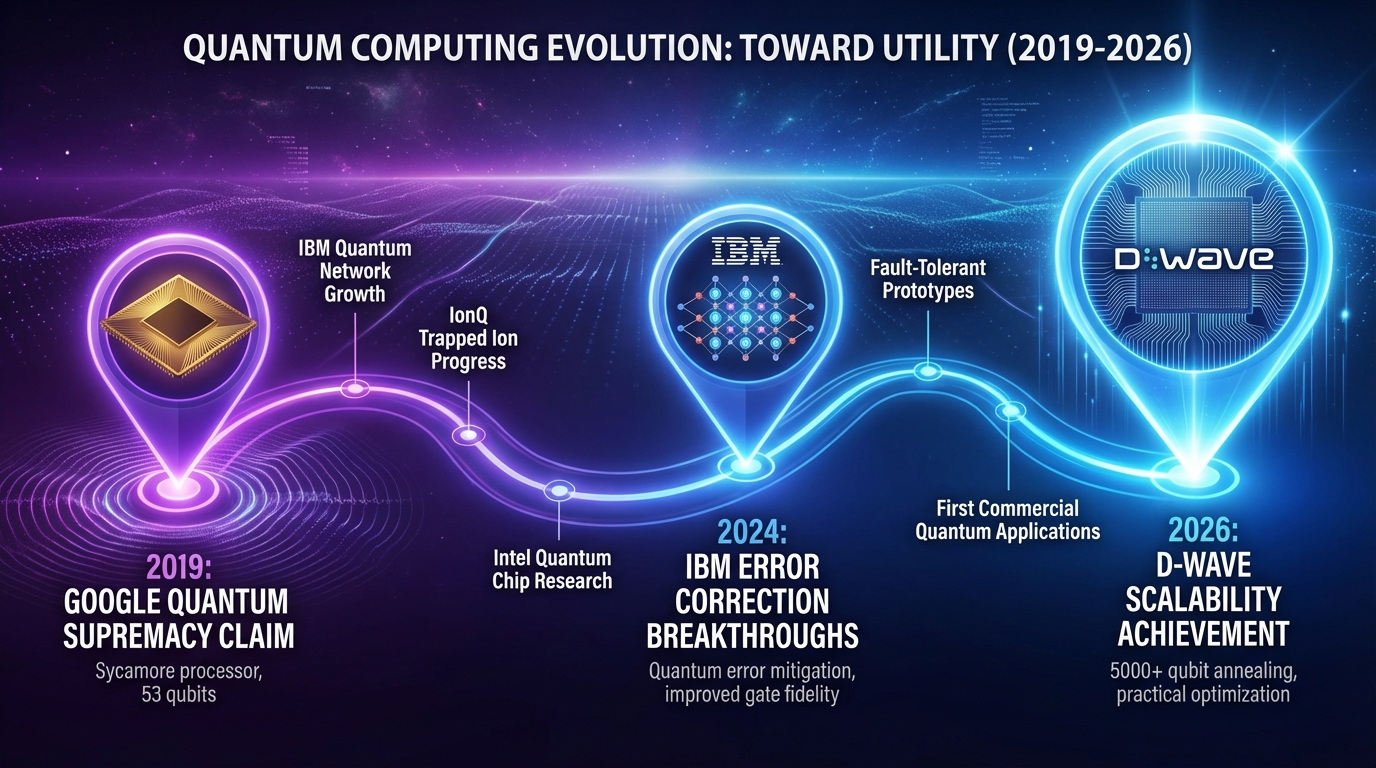

IBM now predicts that the first cases of verified quantum advantage will be confirmed by the wider community by the end of 2026. This is a specific, measurable claim: that quantum computers will demonstrably solve certain problems faster than any classical computer could.

Previous claims of quantum advantage have been controversial. Google’s 2019 supremacy demonstration was criticized because the problem it solved was specifically designed to favor quantum computers rather than being practically useful. D-Wave’s 2024 claim about simulating magnetic materials faced similar scrutiny. Skeptics argued that these demonstrations showed quantum computers could do quantum things quickly, but didn’t prove they could do useful things faster than classical alternatives.

The 2026 predictions are different because they’re backed by concrete technical milestones. IBM expects future iterations of its Nighthawk processor to deliver up to 7,500 gates by the end of the year. Microsoft, in collaboration with Atom Computing, plans to deliver an error-corrected quantum computer to Denmark. QuEra has delivered a quantum machine ready for error correction to Japan’s AIST and is making it available to global customers.

The shift from research demonstrations to commercial deployments represents a maturation of the field. These aren’t experiments showing what might be possible. They’re products designed to solve real problems for paying customers.

Cross-Disciplinary Connections

The quantum computing story connects to broader patterns in scientific and technological progress. The history of technology is filled with examples of “impossible” achievements that turned out to be merely difficult.

In 1895, Lord Kelvin declared that “heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible.” Eight years later, the Wright brothers proved him wrong. The impossibility wasn’t in physics; it was in the assumptions about how to approach the problem. Similarly, the sound barrier was once considered a physical limit on aircraft speed. Pilots who approached it experienced severe buffeting and loss of control. The barrier turned out to be a problem of aircraft design, not fundamental physics.

Quantum computing’s impossible achievements follow this pattern. The wiring problem, the error correction overhead, the fragility of large quantum systems: each seemed like a fundamental limit until someone found a way around it. The limits were real constraints on certain approaches, not absolute boundaries on what’s achievable.

This pattern suggests caution about accepting any current “impossible” as truly impossible. The constraints we accept today often turn out to be constraints on our imagination rather than constraints imposed by nature.

At the same time, the quantum story shows that breaking through impossible requires more than optimism. It requires understanding the problem deeply enough to see where the apparent constraint actually lies. D-Wave didn’t solve the wiring problem by trying harder at the old approach. They reconceptualized what qubit control means. The researchers who broke the error correction scaling curse didn’t just find faster algorithms. They found algorithms that worked differently.

The connection to artificial intelligence deserves mention. The same AI systems that are transforming other fields are now being applied to quantum computing. Google’s AlphaQubit uses machine learning to decode errors more effectively than traditional algorithmic approaches. The intersection of AI systems that learn physics by watching and quantum computing may accelerate progress in both fields.

The Bigger Picture

The quantum computing breakthroughs of early 2026 represent more than technical achievements. They mark a transition from “can quantum computers work?” to “what can quantum computers do?” This is the same transition that personal computers made in the 1980s, that the internet made in the 1990s, and that AI has been making in recent years.

We still don’t know exactly what quantum computers will be best at. Optimization problems, drug discovery, materials science, and cryptography are the usual suspects, but the most important applications may be ones we haven’t imagined yet. The same was true of classical computers: no one in 1946 predicted social media or smartphone apps. The state of space exploration in 2026 shows similar patterns of rapid advancement defying earlier projections.

What we do know is that the field has broken through multiple barriers that seemed fundamental. The wiring problem that couldn’t be solved has been solved. The error correction overhead that seemed inevitable has been largely eliminated. The fragility of large quantum systems has been converted into stability.

The pattern of impossible achievements becoming routine should inform how we think about quantum computing’s future. The constraints that seem absolute today may turn out to be merely the constraints of current approaches. The applications that seem impossible may turn out to be merely waiting for the right conceptual breakthrough.

This doesn’t mean quantum computers will eventually do everything. Some problems really are hard for fundamental reasons. But the track record suggests extreme humility about what’s impossible. The experts who have been most consistently right about quantum computing are the ones who have been most willing to say “I don’t know what the limits are.”

The age of practical quantum computing isn’t just approaching. By multiple measures, it’s already here.