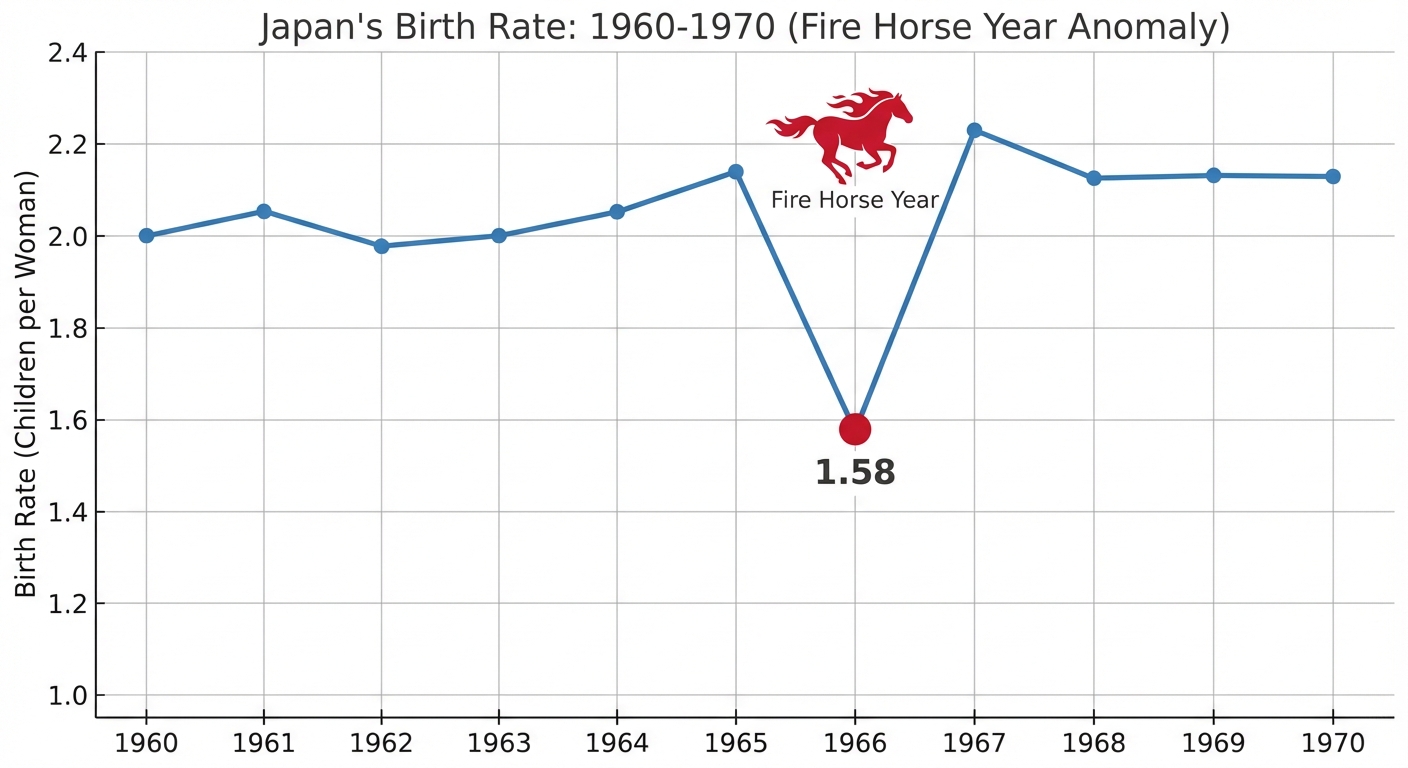

In 1966, something strange happened in Japan. The birth rate, which had been hovering around 2.0 children per woman throughout the decade, suddenly plummeted to 1.6. Hospitals reported nearly 500,000 fewer births than the previous year. The following year, the rate bounced back to normal as if nothing had happened. There was no war, no famine, no epidemic. The cause was something far more unusual: a superstition about horses.

2026 is a Fire Horse year, the first since 1966. In the sexagenary calendar used across East Asia, certain combinations of elements and animals create years with special significance. The Fire Horse, known in Japanese as hinoeuma, carries a centuries-old stigma. According to the belief, women born in Fire Horse years possess a fierce temperament that brings misfortune to their husbands, even shortening their lives. The superstition was powerful enough to convince hundreds of thousands of Japanese families to avoid having children for an entire calendar year.

The question now is whether it will happen again. Japan’s fertility rate has fallen to historic lows, with barely 758,000 births in 2024. If the Fire Horse superstition influences even a fraction of the population, the demographic consequences could be significant. But 2026 is not 1966. Society has changed, beliefs have evolved, and modern Japanese couples may view ancient superstitions very differently than their grandparents did.

The Legend of Yaoya Oshichi

The Fire Horse superstition traces back to the early Edo period (1603-1868), though its exact origins are murky. The earliest versions focused on fire itself: years of the Fire Horse were supposedly prone to conflagrations. In a country where entire cities were built of wood and paper, this was a practical if unfounded concern. But at some point, the superstition shifted from fires to women.

The transformation is often linked to the story of Yaoya Oshichi, a greengrocer’s daughter in 17th-century Edo (modern Tokyo). According to legend, Oshichi fell in love with a temple page she met while her family was sheltering at a temple after a fire destroyed their home. Desperate to see him again, she committed arson, hoping to create another fire that would force her family back to the temple. She was caught and burned at the stake at age 16.

Oshichi was said to have been born in a Fire Horse year, and her story became a cautionary tale about the dangerous passions of Fire Horse women. The connection was likely invented after the fact, but it proved durable. Over the centuries, the superstition hardened into folk wisdom: Fire Horse women are willful, passionate, and dangerous to marry. Families seeking advantageous matches for their daughters avoided Fire Horse years. The stigma extended to the children themselves, who faced discrimination in marriage and employment.

The Demographic Shock of 1966

By the 1960s, Japan had modernized dramatically. It was an industrial powerhouse, a democracy, a society that prided itself on education and scientific thinking. The Fire Horse superstition seemed like an anachronism, a relic of feudal times that surely couldn’t influence behavior in a modern nation.

The 1966 birth data proved otherwise. Births dropped from approximately 1.82 million in 1965 to 1.36 million in 1966, a decline of roughly 25%. The fertility rate fell from 2.14 to 1.58 in a single year. In 1967, births rebounded to 1.94 million, confirming that the dip was a one-year anomaly rather than the start of a trend.

The mechanism was deliberate family planning. Sex detection during pregnancy wasn’t available in 1966, so couples who wanted to avoid having a Fire Horse daughter had to avoid pregnancy altogether. Contraception use increased. Some studies found evidence of elevated abortion rates, though the data is contested. What’s clear is that millions of Japanese families made conscious decisions to delay childbearing by a year to avoid the stigmatized zodiac sign.

The effect was stronger in rural areas, where traditional beliefs held greater sway, than in urban centers. Regions with older populations and more traditional social structures saw larger birth declines. Education also mattered: families with higher education levels were less likely to alter their childbearing plans based on zodiac years. The Fire Horse effect, in other words, was not uniform. It reflected the uneven distribution of traditional beliefs across a rapidly modernizing society.

Children of the Fire Horse

Women born in 1966 grew up in the shadow of the superstition. Though Japanese society had changed enough to make the birth rate drop possible, it changed further in the decades that followed. The stigma against Fire Horse women faded, though it never entirely disappeared.

Research on outcomes for 1966 births shows some lasting effects. Studies found that people born in 1966 had slightly lower educational attainment than those born in adjacent years, possibly because reduced cohort size led to school closures and consolidated classrooms in some areas. In adulthood, 1966-born women reported experiences of discrimination in marriage negotiations, though this declined as arranged marriages became less common.

The children of 1966 are now approaching 60, and their smaller cohort has moved through Japanese society like a demographic bulge in reverse. Fewer kindergarten students, fewer high school graduates, fewer first-time home buyers, and eventually fewer retirees. The echo of a superstition ripples through actuarial tables and pension projections, a reminder that beliefs have consequences that outlast the belief itself.

Will 2026 Repeat 1966?

The arrival of the first Fire Horse year since 1966 has prompted speculation about whether history will repeat. Online discussions in Japan show some awareness of the superstition, and a few commentators have raised concerns about its potential impact on an already fragile birth rate.

The demographic context is vastly different from 1966. Japan’s fertility rate has declined steadily for decades, reaching historic lows below 1.3 children per woman. The approximately 758,000 births recorded in 2024 represent less than half the 1966 figure. Young Japanese couples are already delaying or forgoing childbearing for economic and social reasons that have nothing to do with zodiac years. A superstition-driven decline would compound an existing crisis.

However, most experts doubt that 2026 will see a 1966-style collapse. Arranged marriages, where zodiac compatibility was a serious consideration, have largely disappeared. Modern couples choose their own partners and make their own reproductive decisions based on economic circumstances, career timing, and personal preference rather than folk beliefs. Social media ensures that any attempt to revive Fire Horse fears would face immediate ridicule and pushback.

Government projections actually show 2026’s birth rate declining at roughly the same pace as recent years, around -0.49% compared to -0.45% in 2024. The Fire Horse isn’t driving births lower. Economic factors, housing costs, childcare availability, and changing attitudes toward marriage are doing that work without any help from superstition.

The Persistence of Belief

The Fire Horse story illuminates something important about how beliefs work in society. Superstitions don’t require universal acceptance to have effects. Even if most people don’t believe in Fire Horse curses, enough people acting on the belief can create measurable demographic shifts. The 1966 birth decline didn’t require everyone in Japan to be superstitious. It required a critical mass of families on the margin who might have had children that year but decided to wait.

Beliefs also persist in weakened forms. Few Japanese today would openly admit to avoiding Fire Horse years, but the superstition exists as cultural knowledge, something people know about even if they don’t believe it. That cultural memory can influence behavior in subtle ways, creating hesitation or doubt even among people who consider themselves rational. The question isn’t whether people believe in Fire Horse curses literally but whether enough people feel even mild unease about the association.

The Bigger Picture

The Year of the Fire Horse is ultimately a story about how culture shapes behavior in ways that ripple across generations. A folk belief about women’s temperament, itself probably invented to explain a notorious crime, became powerful enough to affect the reproductive decisions of millions of families. The children not born in 1966 represent a kind of demographic counterfactual, lives that weren’t lived because of a story about a greengrocer’s daughter and a fire.

2026 will probably not repeat 1966. Japanese society has changed too much, traditional beliefs have weakened too far, and modern couples have too many other concerns to worry about zodiac curses. But the Fire Horse remains in cultural memory, a reminder that we are not always the rational actors we imagine ourselves to be. The superstitions of the past still cast shadows, even when we think we’ve outgrown them.

Whether any babies born in 2026 face residual stigma from their Fire Horse birth year remains to be seen. The women of 1966 mostly escaped the worst predictions of the old belief, living full lives that contradicted the superstition about their dangerous temperaments. Perhaps the Fire Horse year is most interesting not as a predictor of personality but as a window into how societies change, how beliefs fade, and how the echoes of old stories still shape the world in unexpected ways.

Sources: Japan Vital Statistics 1965-1967, Nippon.com research on Fire Horse demographic effects, World Bank demographic analysis, historical accounts of Yaoya Oshichi, Japanese zodiac and sexagenary calendar traditions.