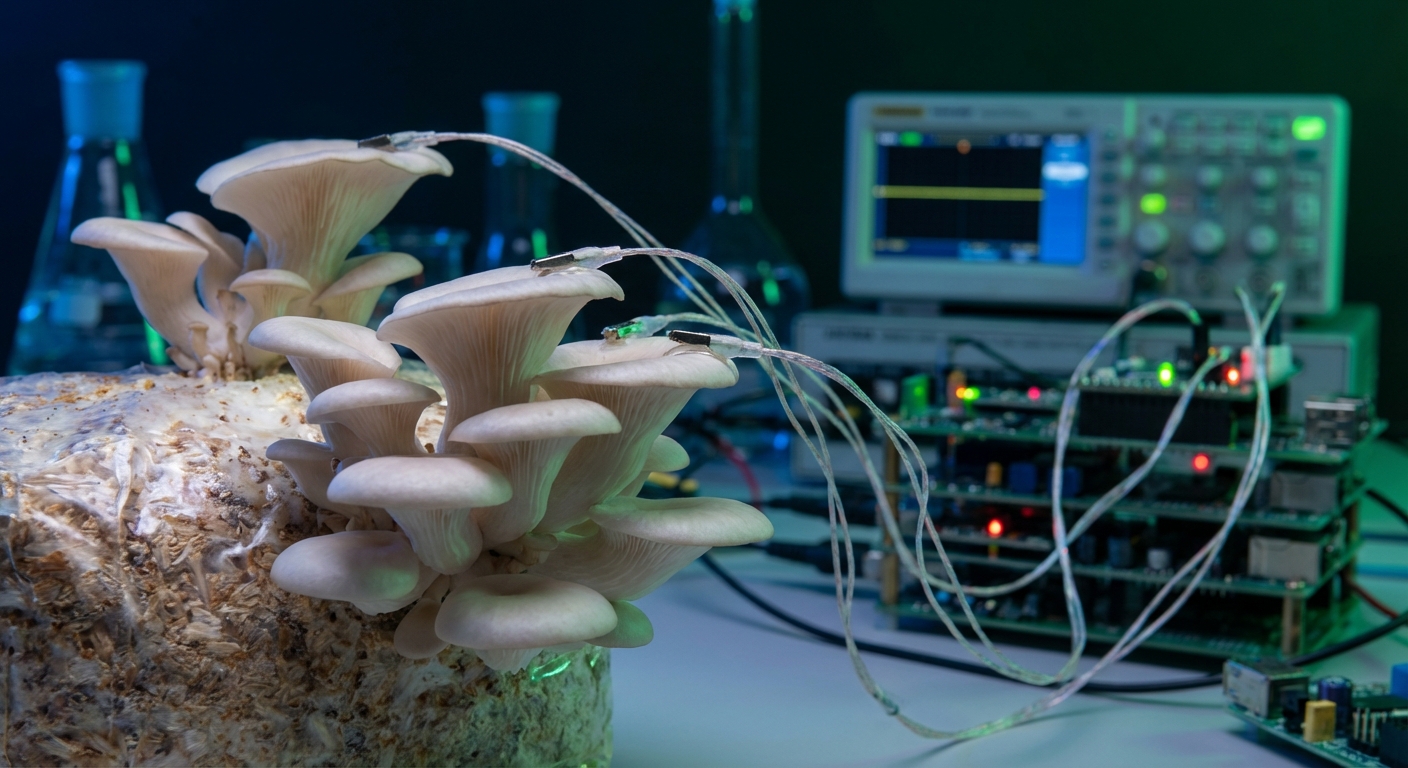

The mushrooms didn’t know they were making art. Oyster fungi, the same species you might sauté with garlic, were hooked up to electrodes that captured the electrical signals constantly pulsing through their mycelium. Those signals were processed and fed into a robotic arm. The arm played piano. It generated spoken-word poetry. It painted abstract self-portraits on canvas. The mushrooms were, in a sense, expressing themselves through technology they couldn’t possibly understand.

The project, created by researchers exploring the intersection of biology and robotics, sounds like science fiction or perhaps an elaborate art installation. But the underlying science is serious and potentially revolutionary. Fungi generate bioelectrical signals similar to the neural activity in animal brains. These signals respond to environmental stimuli, change with the mushroom’s metabolic state, and propagate through the fungal network in patterns that some researchers compare to primitive cognition.

By learning to read and interpret these signals, scientists are opening new frontiers in bioelectronics, the field that bridges living systems and electronic devices. The mushroom-controlled robot arm is a proof of concept, a demonstration that biological electrical activity can drive mechanical systems in real time. The next steps could include biosensors that use fungi to detect environmental pollutants, living computers that process information through organic networks, and hybrid systems that combine the adaptability of biology with the precision of machines.

The Electrical Life of Fungi

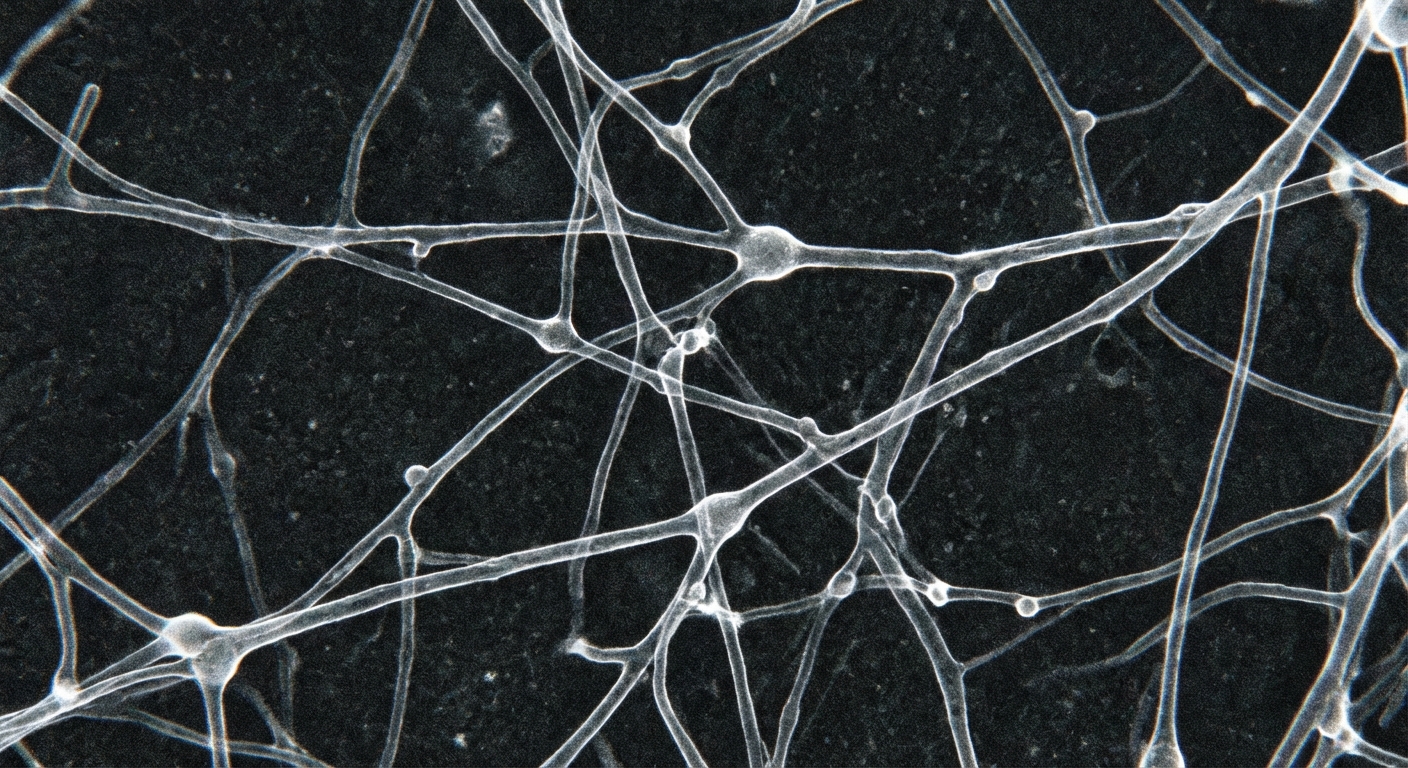

Most people don’t realize that mushrooms are electrical. The visible fruiting body, the cap and stem we eat, is just a small part of a much larger organism. Underground, a network of thread-like hyphae called mycelium extends through the soil, sometimes covering acres. This network is the fungus’s main body, and it’s constantly buzzing with electrical activity.

Fungal electrical signals were first detected in the 1990s, but their significance wasn’t appreciated until recently. The signals propagate through the mycelium at rates similar to nerve impulses in simple animals. They respond to stimulation: touch a mushroom, change the temperature, alter the humidity, and the electrical patterns change. Some researchers have identified distinct types of signals that might correspond to different “states” of the fungus.

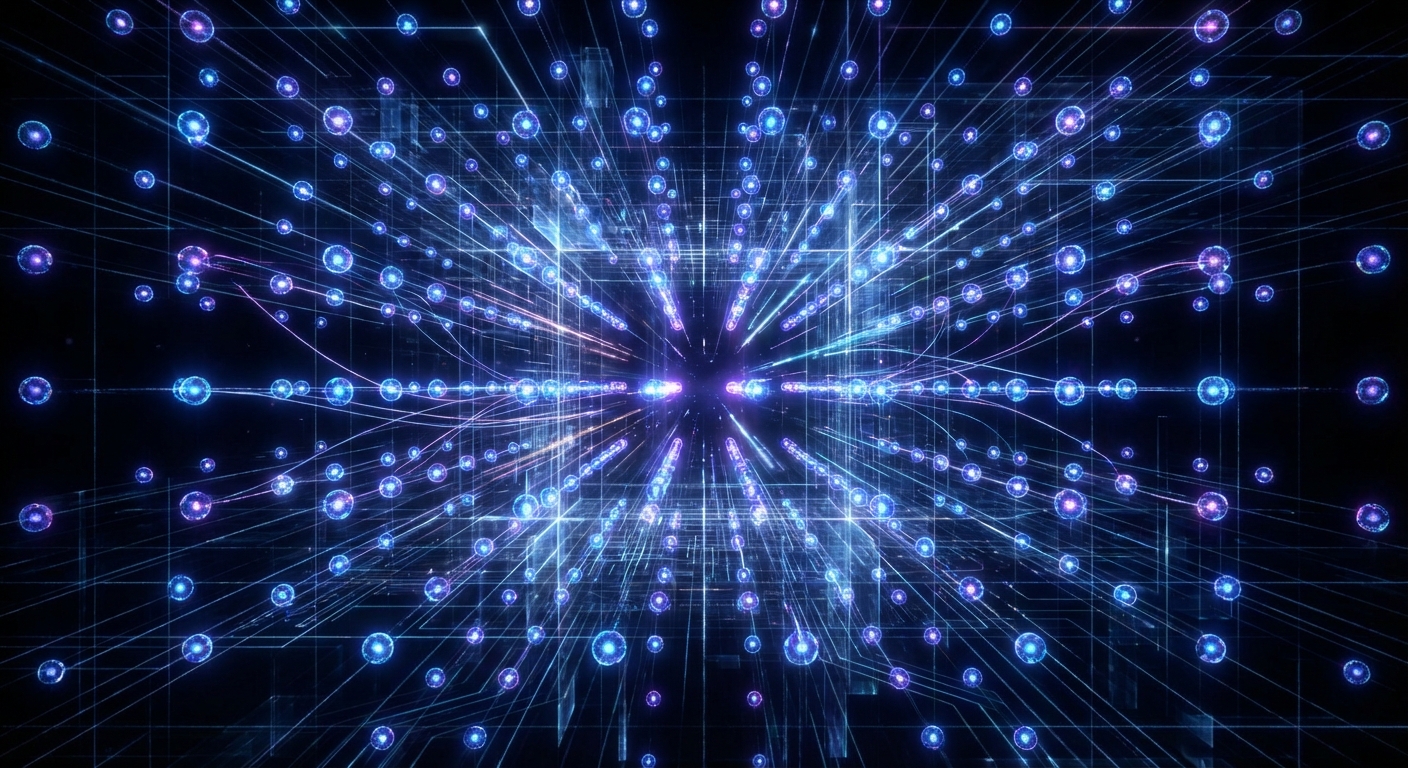

The comparison to neural activity is provocative. Nobody claims mushrooms are conscious or that they think in any way resembling animal cognition. But the electrical patterns in mycelium share structural features with neural networks: signals that propagate, branch, and integrate across distributed systems. Some researchers have suggested that fungal networks might perform information processing that, while alien to us, qualifies as a primitive form of computation.

The 2022 paper that proposed mushroom “language” attracted significant attention. Researcher Andrew Adamatzky analyzed electrical signals from several fungal species and found recurring patterns that he compared to words, with a vocabulary of roughly 50 distinct signal types. The claim remains controversial, as many scientists argue the patterns could be random noise or simple physiological processes rather than meaningful communication. But even skeptics acknowledge that fungal electrical activity is more complex than previously assumed.

From Signals to Actions

The mushroom-robot interface works by capturing these bioelectrical signals and translating them into machine instructions. Electrodes attached to the fungal surface pick up voltage fluctuations, which are amplified and processed by a computer. Software maps specific signal patterns to specific robotic actions. When the mushroom produces a particular electrical pattern, the robot arm moves in a corresponding way.

The mapping is somewhat arbitrary, like assigning meanings to the letters of an unfamiliar alphabet. The mushroom isn’t “intending” to play a particular note or make a particular brush stroke. But the relationship isn’t entirely random either. Changes in the mushroom’s environment, like variations in light, humidity, or the presence of certain chemicals, alter its electrical patterns, which alter the robot’s behavior. The system responds to stimuli, creating a feedback loop between the fungal organism and its mechanical extension.

The art produced by these systems has an organic quality that purely algorithmic art often lacks. The mushroom’s electrical patterns aren’t designed; they emerge from the fungus’s metabolism, its growth patterns, its response to microconditions in its environment. This gives the resulting art an unpredictability and complexity that feels alive, because in a sense it is.

Applications Beyond Art

The artistic applications are attention-grabbing but represent just the surface of what fungal bioelectronics might accomplish. More practical applications are already being explored.

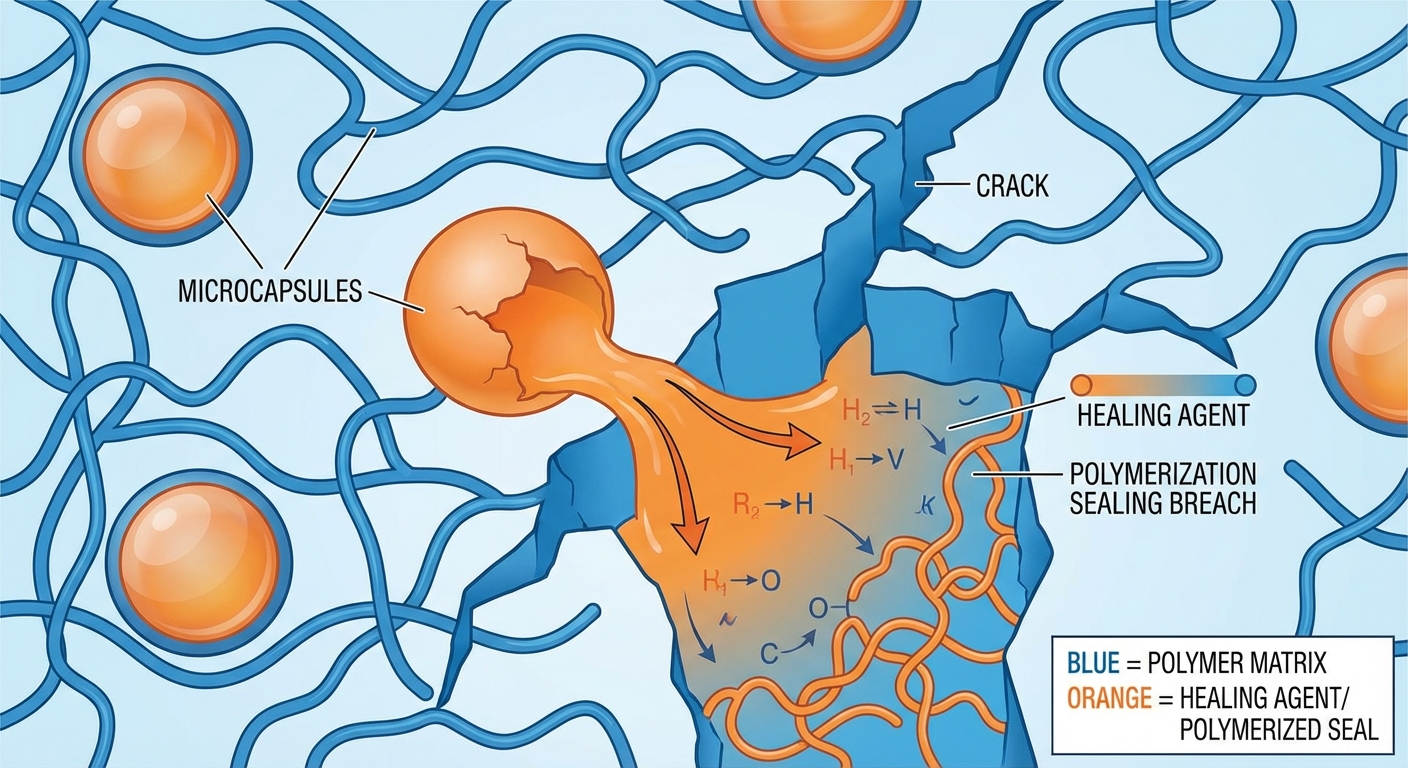

Environmental sensing is a natural fit. Fungi are extraordinarily sensitive to their chemical environment. Mycelium networks in soil interact with hundreds of different compounds, and their electrical activity changes in response to pollutants, heavy metals, and other contaminants. A fungal biosensor could potentially detect environmental hazards more cheaply and with greater sensitivity than conventional electronic sensors.

Researchers are also exploring fungal materials for sustainable electronics. Growing circuit boards from mycelium rather than manufacturing them from petroleum-based plastics could reduce electronic waste’s environmental footprint. The electrical properties of fungi mean these biological materials could potentially serve active roles in circuits, not just as structural substrates.

The most speculative applications involve using fungal networks as biological computers. The mycelium’s distributed architecture, with its parallel pathways and adaptive connections, resembles the structure of neural networks used in artificial intelligence. Theoretically, a sufficiently complex fungal network could perform computations, using its natural electrical signaling to process information. Such a system would be radically different from silicon-based computers but might excel at certain types of problems, particularly those involving pattern recognition and environmental response.

The Bigger Picture

The mushroom-controlled robot is ultimately a statement about the boundaries between living and artificial systems. Those boundaries are becoming increasingly porous. We already have brain-machine interfaces that allow paralyzed patients to control robotic limbs with their thoughts. We have synthetic biology that engineers organisms to produce useful compounds. We have machine learning systems that mimic aspects of biological cognition.

Fungal bioelectronics sits at a strange position in this landscape. Unlike brain-machine interfaces, the biological component isn’t sentient. Unlike synthetic biology, the goal isn’t to make the organism produce a specific output but to harness whatever it naturally produces. The mushroom becomes something like a living random number generator, introducing biological unpredictability into mechanical systems.

This has philosophical implications beyond the practical applications. What does it mean when an organism without a brain, without anything we’d recognize as a mind, controls a machine? The mushroom isn’t intending anything, yet its actions have consequences in the physical world. It’s agency without intention, causation without consciousness.

Perhaps the mushroom-controlled robot is best understood as a collaboration between radically different forms of intelligence, if fungal electrical patterns can be called intelligence at all. The human designers created the system and defined the mappings. The electronic processors translated signals into actions. The robot arm executed movements with mechanical precision. And at the center, generating the patterns that drive everything else, sits a humble oyster mushroom, doing what mushrooms have done for hundreds of millions of years: living, growing, and pulsing with electrical activity that science is only beginning to understand.

Sources: Bioelectronics research on fungal electrical signaling, Adamatzky language hypothesis studies, robotic systems integration projects, mycelium materials science, environmental biosensor development.