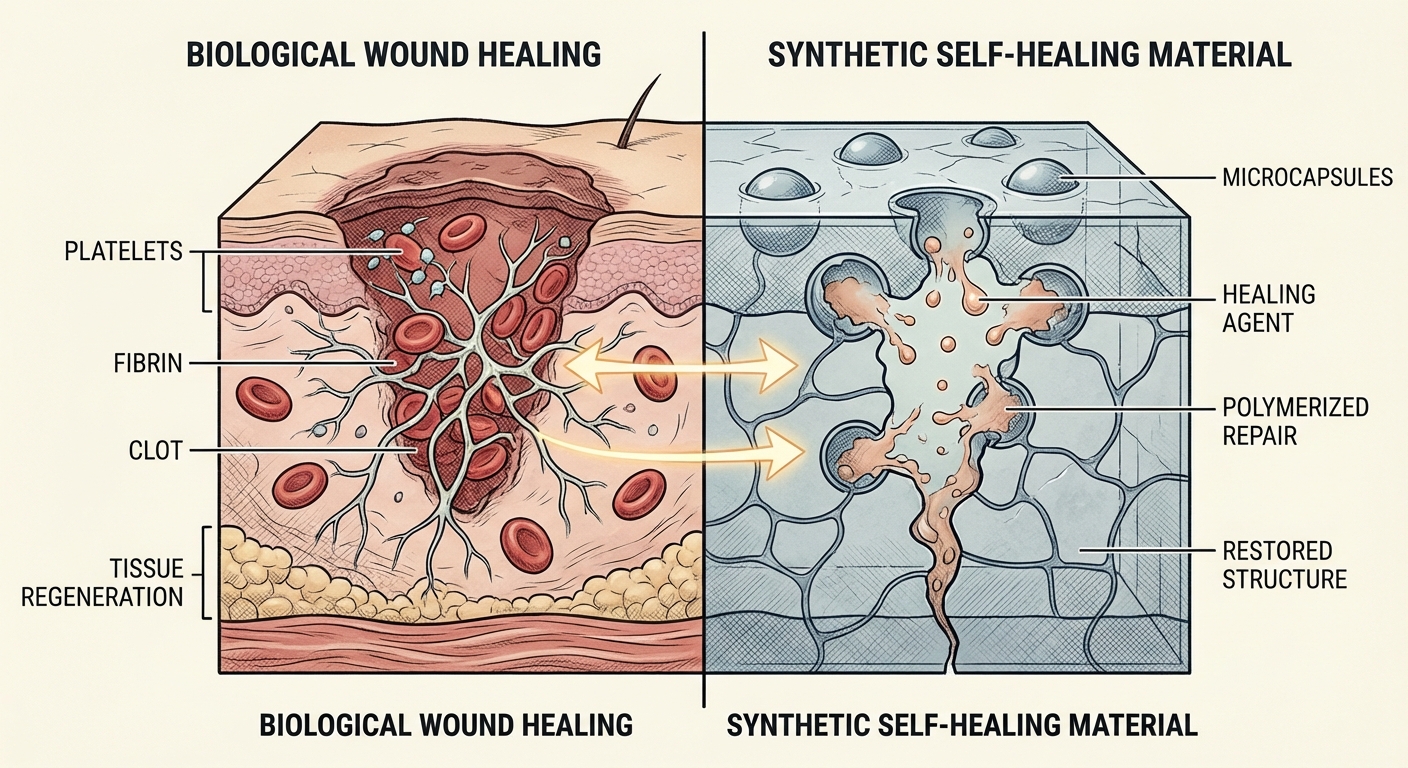

When you cut your skin, you don’t have to think about repairing it. Platelets rush to the wound, clotting factors cascade through a complex chemical dance, and within days, new tissue bridges the gap. Your body has been perfecting this trick for hundreds of millions of years. Now, for the first time, engineers have figured out how to teach materials to do the same thing.

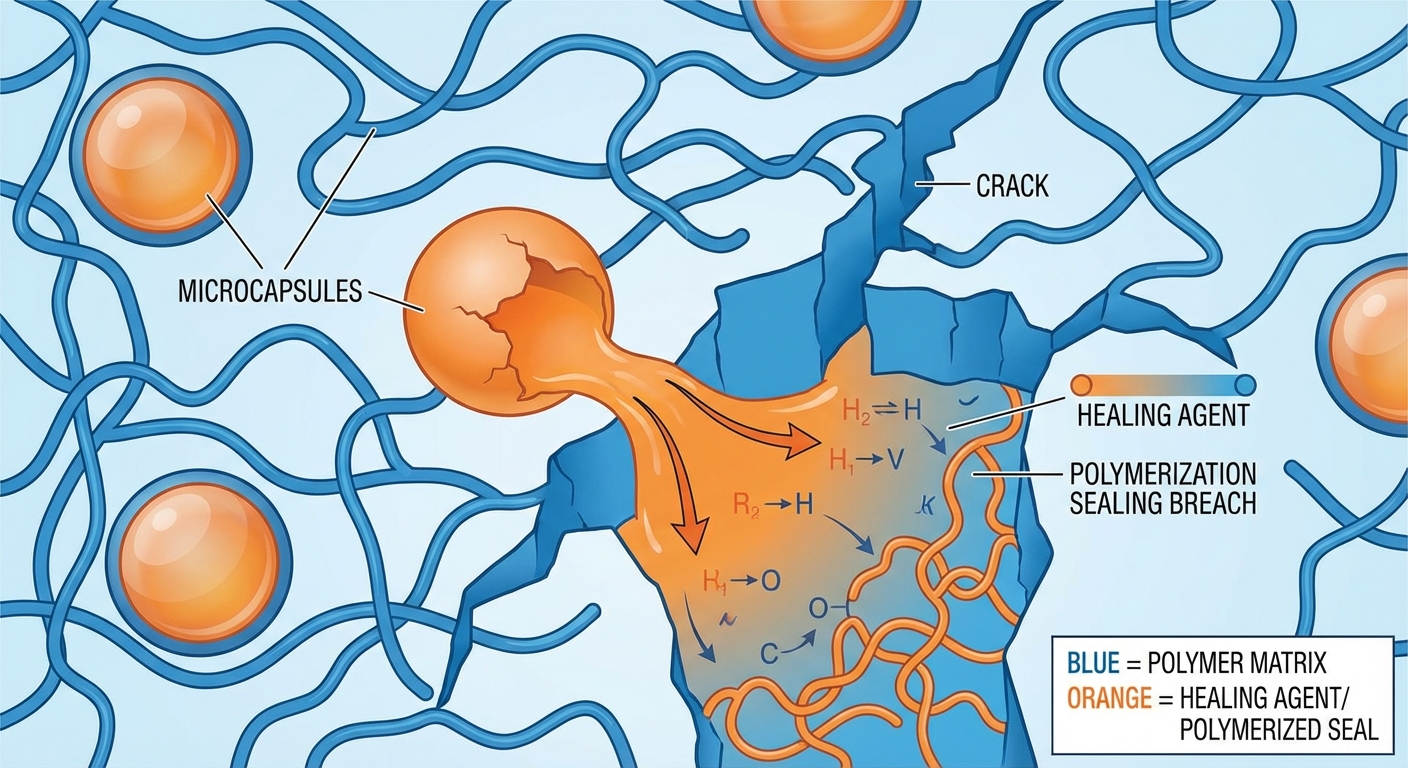

The breakthrough, which materials scientists are calling one of the most significant of 2026, involves embedding microscopic capsules into coatings and composites. When damage occurs, whether from impact, stress, or environmental wear, these capsules rupture and release healing agents that flow into cracks and polymerize within hours. The material essentially bleeds, clots, and heals, all without any human intervention.

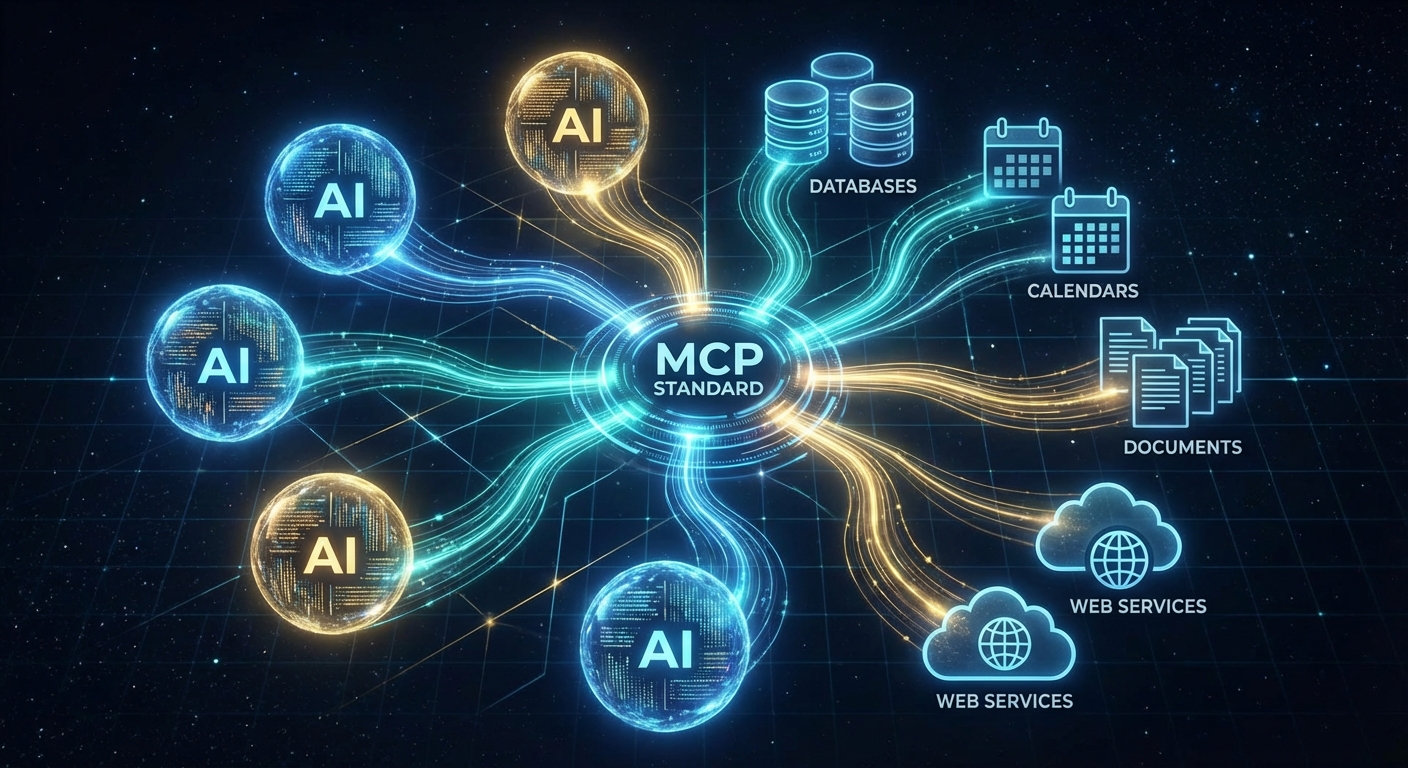

This isn’t science fiction or a laboratory curiosity. Recent advances in microcapsule engineering, including shell stability and controlled release mechanisms, have finally made self-healing coatings viable for industrial applications. And when you combine this technology with Internet of Things sensors that can detect damage in real time, you get materials that not only heal themselves but can report on their condition throughout their entire lifecycle.

How Self-Healing Works

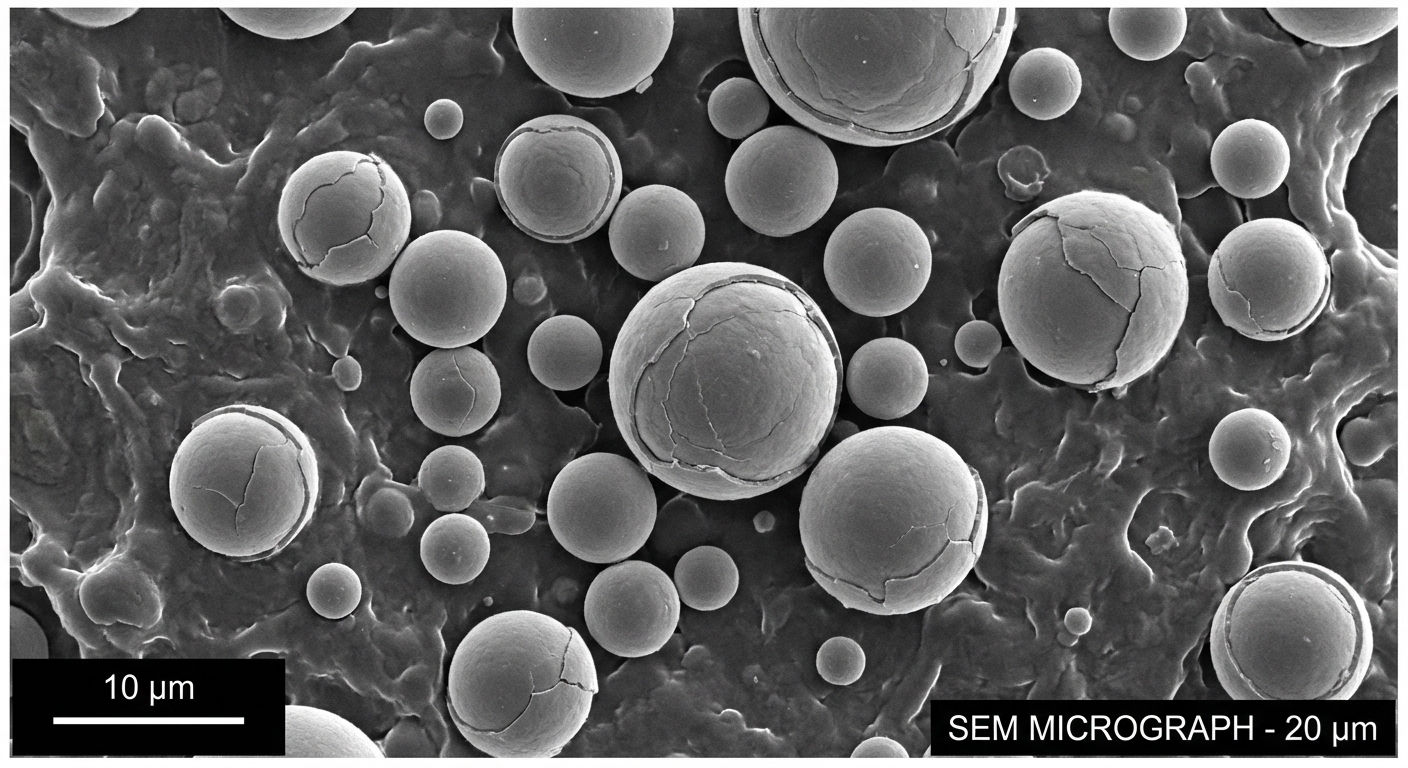

The core principle is deceptively simple: store the medicine inside the patient. Engineers embed tiny capsules, typically between 50 and 300 micrometers in diameter (about the width of a human hair), throughout a material’s matrix. These capsules contain liquid monomers or other healing agents, protected by a shell that remains stable under normal conditions but ruptures when stress fractures propagate through the material.

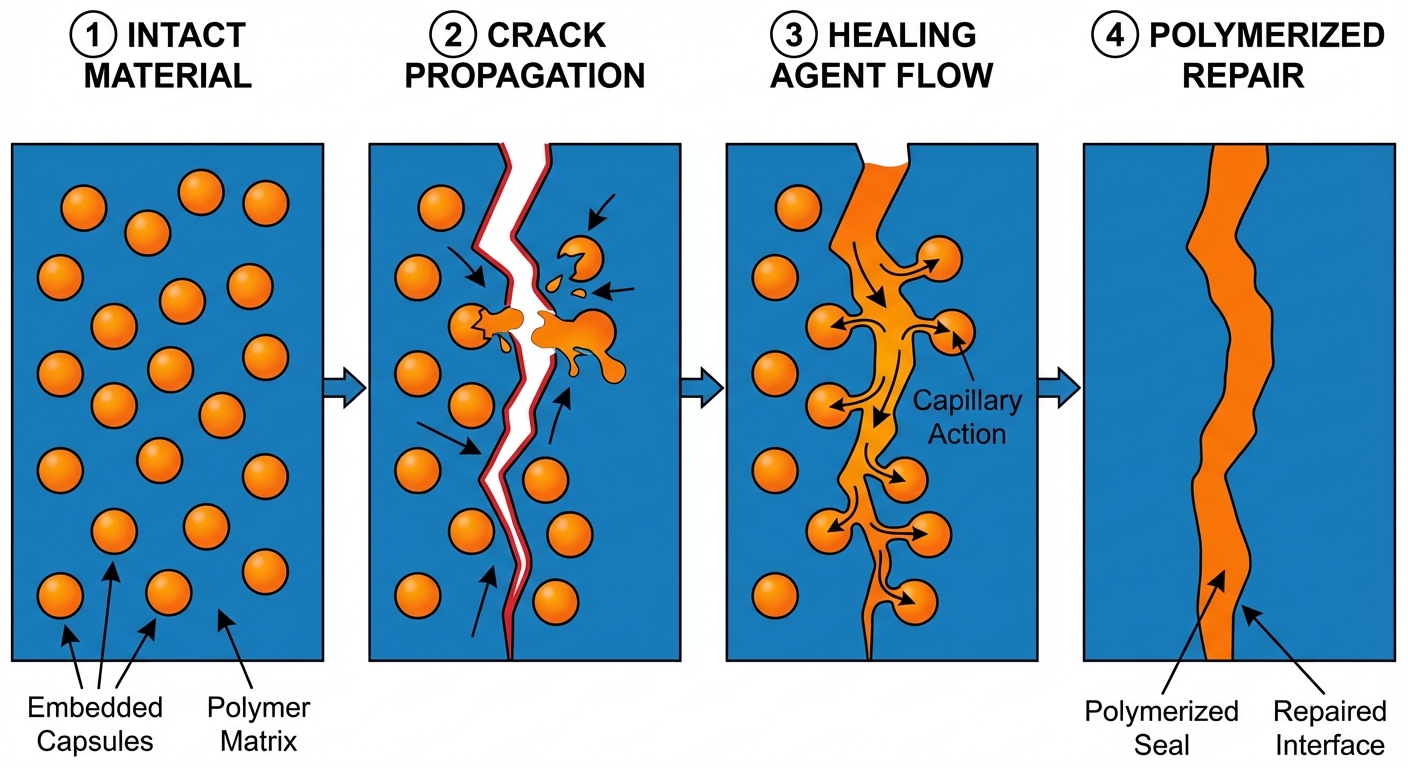

When a crack forms and encounters a capsule, it breaks the shell open. The liquid healing agent then wicks into the crack through capillary action, the same force that makes water climb up a narrow tube or paper towel. Once the healing agent contacts a catalyst (either embedded in the surrounding material or mixed with a second component from another capsule), it polymerizes, filling the crack with solid material that bonds to the surrounding matrix.

The elegance lies in the autonomy. No sensors are needed to detect the damage. No signals need to be sent. The damage itself triggers the repair. It’s the same principle that makes your blood clot: the injury exposes factors that weren’t exposed before, and the chemistry takes care of the rest.

The Engineering Challenges

If the concept is simple, why did it take so long to make it work? The challenges turn out to be formidable, each requiring its own set of innovations to solve.

First, the capsules themselves must survive the manufacturing process. Many coatings are applied at high temperatures or under significant mechanical stress. Early capsule designs would rupture during application, releasing their healing agents before they were ever needed. Modern shells use sophisticated polymer chemistry to remain stable during processing while still being weak enough to break when cracks propagate through the material.

Second, the healing agent must remain liquid and reactive for years, possibly decades, while stored inside the capsule. Many reactive chemicals degrade over time, especially when exposed to trace moisture or oxygen that diffuses through the shell. Researchers developed multi-layer capsule architectures and oxygen-scavenging additives to extend shelf life to industrially relevant timescales.

Third, the healed material must actually restore functionality. It’s not enough to fill a crack with any solid material; the repair needs to provide meaningful structural integrity or barrier properties. Early systems achieved only 60 to 70 percent recovery of original strength. Current systems, using carefully matched healing chemistry and capsule formulations, can restore 90 percent or more of original properties in some applications.

Finally, for the Internet of Things integration that makes these materials truly revolutionary, engineers had to develop sensors small and robust enough to be embedded alongside the capsules without interfering with the healing process. Fiber optic strain sensors, piezoelectric elements, and even conductive nanoparticle networks can now be woven into self-healing composites, creating materials that know their own condition.

Where Self-Healing Matters Most

The applications that justify the added complexity of self-healing materials share a common thread: the cost of failure is extremely high, but the cost of inspection and repair is also substantial. In these contexts, materials that can extend their own service life without human intervention offer transformative economics.

Aerospace is an obvious candidate. Aircraft structures experience millions of stress cycles over their operational lives, and tiny cracks can propagate to catastrophic failure if undetected. Current practice involves extensive inspection regimes, often requiring aircraft to be taken out of service. Self-healing composites could dramatically extend inspection intervals while simultaneously providing a backup safety margin.

Pipeline infrastructure presents similar economics. Oil, gas, and water pipelines span thousands of miles, often buried underground or submerged underwater. Corrosion and mechanical damage create slow leaks that can persist undetected for months. Self-healing coatings that automatically seal small breaches could prevent environmental damage while reducing the need for physical inspection of remote infrastructure.

Wind turbine blades, which endure punishing conditions at the tips of 300-foot structures, have emerged as an early commercial application. The cost of repairing or replacing damaged blades is enormous, often requiring specialized cranes and taking turbines offline for weeks. Self-healing surface coatings that address erosion damage automatically could significantly improve the economics of wind power.

The Biological Inspiration

The parallels between engineered self-healing and biological wound healing are not coincidental. Many research programs explicitly study biological systems to identify principles that can be translated into synthetic materials.

Blood clotting, for instance, involves a cascade of chemical reactions where each step activates the next. This amplification strategy, in which a small trigger produces a large response, has been adapted into some self-healing systems. Rather than storing enough healing agent to fill every possible crack, these materials store smaller quantities of reactive precursors that can generate larger volumes of solid material through chain reactions.

Tree resin provides another model. When bark is damaged, many trees exude sticky resin that seals the wound and has antimicrobial properties. The resin is stored under pressure in specialized ducts, ready to flow when the barrier is breached. This “pressurized reservoir” concept has inspired vascular self-healing systems, where networks of hollow channels carry healing agents through the material, providing a continuous supply rather than discrete capsules.

Perhaps the most sophisticated biological inspiration comes from bone. Unlike most tissues, bone doesn’t just heal damage; it actively remodels itself in response to mechanical loading, strengthening areas under stress and resorbing material where it’s not needed. Researchers are working on materials that could similarly adapt their properties over time, though this remains largely at the laboratory stage.

The Bigger Picture

Self-healing materials represent more than an incremental improvement in engineering. They embody a philosophical shift in how we think about the relationship between design, manufacturing, and maintenance.

Traditional engineering assumes that materials are static: you characterize their properties, design around those properties, and then manage degradation through inspection and repair. Self-healing materials challenge this assumption. The material itself becomes an active participant in maintaining its own integrity, with properties that change over time as damage occurs and is repaired.

This shift has implications beyond the immediate applications. If materials can heal themselves, what else can they do? Already, researchers are developing materials that can sense their environment and change color to indicate stress levels, or that can adjust their stiffness in response to temperature. The microcapsule approach pioneered for self-healing is being adapted to deliver corrosion inhibitors, antimicrobial agents, and even fragrance compounds.

The integration with IoT sensors points toward an even more transformative possibility: materials that are genuinely intelligent, not just in the metaphorical sense of responding to their environment, but in the sense of being connected to digital networks that can aggregate data from millions of sensors, predict failures before they occur, and even coordinate repair activities across entire infrastructures.

For now, the first industrial self-healing coatings are just reaching the market. But the trajectory is clear. Our great-grandchildren may find it as strange that materials couldn’t repair themselves as we find it strange that people once used leeches for medicine. The technology is still young, but the principle, borrowed from billions of years of biological evolution, is proven. Materials that heal themselves are no longer a future promise. They’re here.