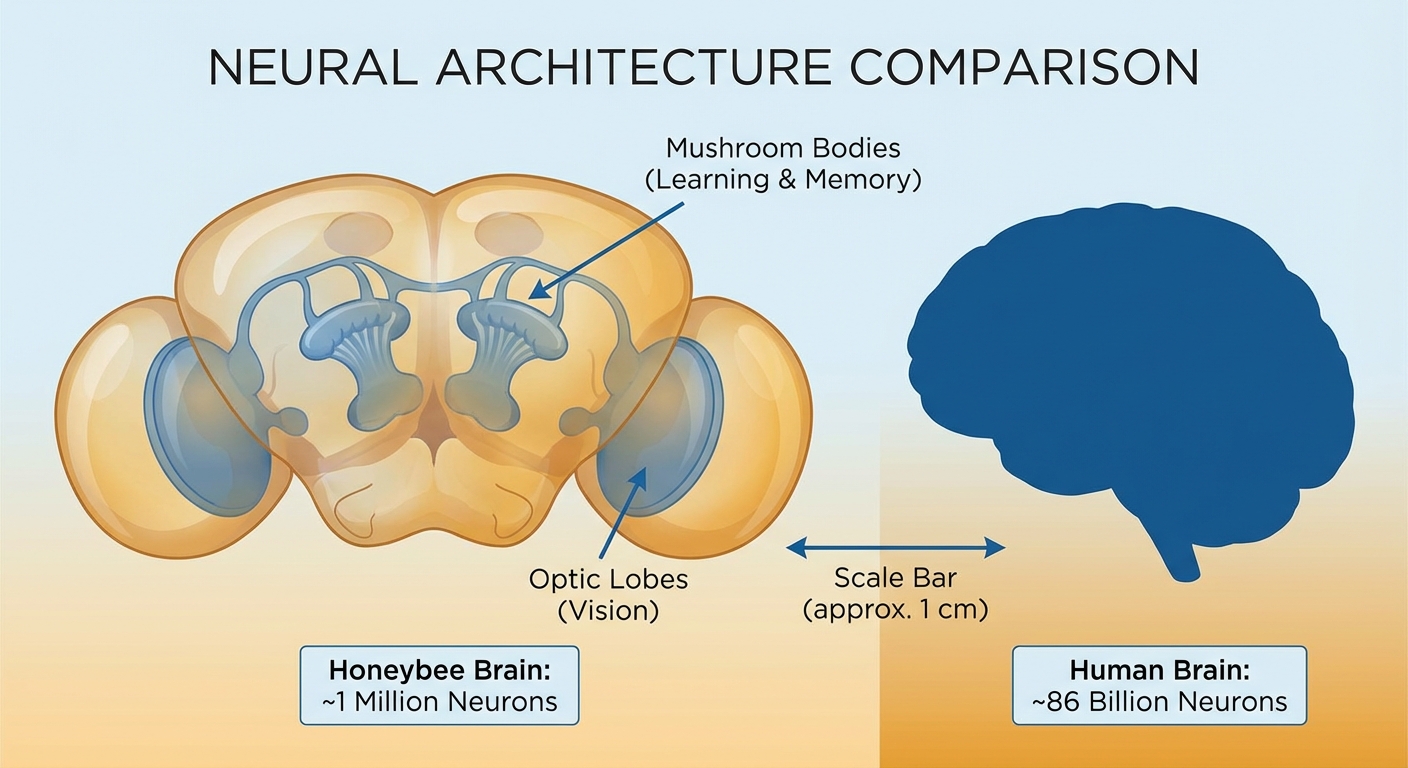

Here’s a test you can try at home. Hold up four fingers on one hand and one finger on the other. A honeybee trained to recognize the number three will fly toward neither option, then check again, then make a choice. Usually, it chooses to fly left toward the smaller number. This preference, researchers discovered, isn’t random. Bees appear to have a mental number line, ordering quantities from left to right just like most humans do. They can count to at least five, understand that zero is less than one, and perform basic addition and subtraction. All of this happens in a brain smaller than a sesame seed, containing roughly one million neurons compared to the human brain’s 86 billion.

The discoveries emerging from bee cognition research are forcing scientists to reconsider fundamental assumptions about intelligence, consciousness, and the relationship between brain size and mental capability. These tiny insects are proving that sophisticated thought doesn’t require sophisticated hardware.

The Miniature Calculator

A honeybee’s brain is smaller than one cubic millimeter. Hold a grain of rice between your fingers and you’re looking at something larger than the entire organ responsible for navigation, communication, memory, and mathematical reasoning in one of Earth’s most successful species. The disparity between bee brain size and bee cognitive ability has become one of the most productive puzzles in neuroscience.

Research from Queen Mary University of London demonstrated that bee counting could theoretically be accomplished with just four neurons. The team simulated a miniature brain on a computer with four nerve cells, far fewer than a real bee possesses, and showed it could count small quantities accurately. The key wasn’t processing power but processing strategy. The simulated brain counted by inspecting items sequentially, focusing on one element before moving to the next, rather than surveying all items simultaneously as humans typically do.

This sequential inspection strategy appears to match how real bees count. When presented with arrays of shapes, bees scan each item individually before making numerical judgments. The approach reduces computational demands dramatically. Instead of needing neurons dedicated to simultaneous pattern recognition, bees can count using circuits that track “one more” or “one less” as they inspect.

Professor Lars Chittka, a leading researcher in bee cognition, explained the implications: “These findings add to the growing body of work showing that seemingly intelligent behaviour does not require large brains, but can be underpinned with small neural circuits that can easily be accommodated into the microcomputer that is the insect brain.” Intelligence, it turns out, is less about raw neural capacity and more about efficient algorithms.

Mental Number Lines

The discovery that bees have mental number lines came from a deceptively simple experiment. Researchers trained bees to recognize a specific quantity, then presented them with two side-by-side options representing different numbers. When the options included a smaller number, bees flew left. When the options included a larger number, they flew right. The left-to-right ordering of small-to-large matches the pattern found in most human cultures.

This finding, published in research examining spatial preferences and magnitude associations in honeybees, suggests something profound about the nature of numerical cognition. Humans tend to conceptualize numbers spatially, imagining them arranged along a line from left to right (at least in cultures that read left to right). We assumed this was a product of cultural learning, of seeing number lines in classrooms and reading text in a particular direction. But bees have never seen a classroom. Their left-to-right numerical preference appears to be biological.

The connection may lie in brain lateralization. Bee brains, like human brains, process information differently in their left and right hemispheres. The same asymmetry appears in chickens and human infants, both of which also show left-to-right number ordering. Researcher Martin Giurfa suggests this might be “an inherent property to these lateralized brain systems.” The mental number line, rather than being a human invention, may be an emergent property of how asymmetrical brains naturally organize magnitude information.

The implications extend beyond curiosity about bee minds. If numerical cognition follows similar patterns across wildly different species, it suggests that mathematics isn’t purely a human construction but reflects something about how any brain, regardless of size or evolutionary history, naturally processes quantity.

Beyond Counting: Addition and Subtraction

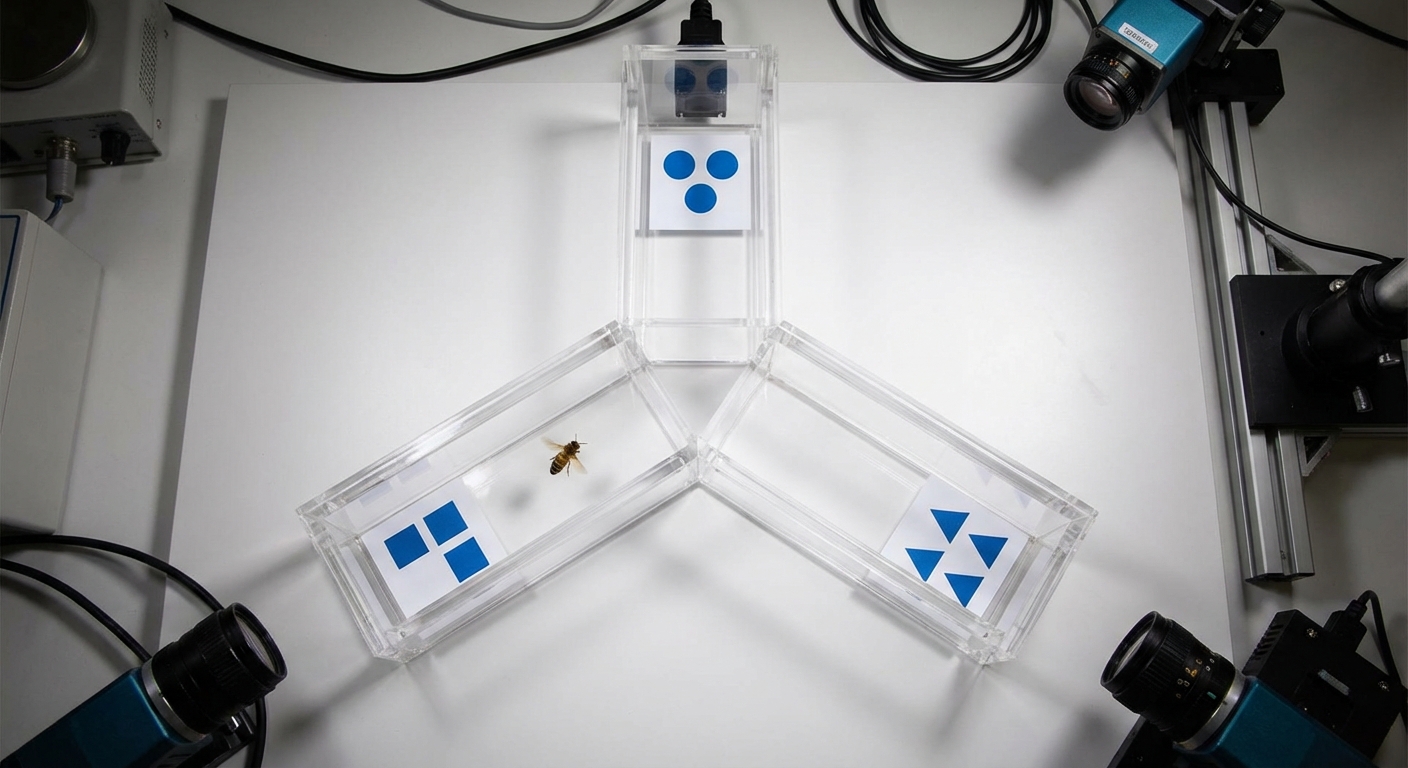

Counting is impressive enough. But bees can also perform arithmetic. In experiments published in Science Advances, researchers trained honeybees to associate colors with mathematical operations. Blue meant “add one.” Yellow meant “subtract one.” Bees learned to fly into Y-shaped mazes where the entrance showed a number of shapes, and they had to choose the exit displaying either one more or one fewer shapes, depending on the color.

The bees succeeded. When shown three blue shapes at the entrance, they chose the exit with four shapes. When shown three yellow shapes, they chose two. They learned the rules and applied them to unfamiliar problems, demonstrating that they understood the abstract relationship between color, operation, and quantity.

This kind of symbolic reasoning was once considered uniquely human. It requires multiple cognitive steps: recognize the number of shapes, recall which color means which operation, perform the calculation, and choose the correct answer. Each step draws on different mental capacities. The fact that bees can coordinate all of them suggests their cognitive architecture is far more sophisticated than brain size would predict.

Even more remarkably, bees understand zero. In separate experiments, bees trained to choose “less” reliably selected an empty stimulus over any number of shapes. They grasped that nothing is less than something, a concept that human children struggle with until around age four and that many ancient civilizations never developed mathematically. Zero is abstract in a way that counting objects isn’t. It represents the absence of quantity, which is conceptually harder than representing quantity itself.

The Waggle Dance: Mathematics in Motion

Bee numerical cognition doesn’t exist in isolation. It connects to one of nature’s most sophisticated communication systems: the waggle dance. When a forager bee discovers a good food source, she returns to the hive and performs a figure-eight dance on the vertical comb surface. The dance communicates three pieces of information: the direction of the food relative to the sun, the distance to the food, and the quality of the source.

Direction is encoded in the angle of the straight “waggle” portion of the dance relative to vertical. If the waggle run points straight up, the food is in the direction of the sun. If it angles 45 degrees to the right, the food is 45 degrees to the right of the sun. Distance is encoded in the duration and intensity of the waggle: longer waggle runs mean farther distances. Quality is communicated through how vigorously and repeatedly the bee dances.

Recent research using the GeoDanceHive, a specialized observation hive with continuous recording capabilities, has revealed new subtleties in how bees encode and decode dance information. Researchers found non-linear relationships between waggle duration and actual distance, and discovered that recruit bees search more precisely than the dance information alone would suggest. Somehow, bees are either interpreting the dances with additional contextual knowledge or the dances contain information we haven’t yet decoded.

Even more intriguing, researchers at Virginia Tech found that dances describing slightly exaggerated distances, telling recruits to “overshoot” the actual food location, were more successful than accurate dances. This suggests the waggle dance may have evolved to optimize search patterns rather than simply transmit coordinates. The mathematics of communication has been shaped by the mathematics of foraging efficiency.

The connection between numerical cognition and dance communication isn’t accidental. Both require bees to process and represent quantities: numbers of items, angles of direction, durations of time. The neural machinery that enables counting may be the same machinery that enables the waggle dance’s sophisticated spatial encoding.

Social Learning and Mathematical Culture

The waggle dance reveals another dimension of bee cognition: social learning. Bees don’t hatch knowing how to dance perfectly. Research published in Science showed that correct waggle dancing requires learning from experienced dancers. Bees raised without exposure to older dancers’ performances produced disordered dances with significant errors in angle and distance encoding.

Some of these errors could be corrected through experience. Angle accuracy improved as bees practiced. But distance encoding was “set for life.” Bees that never learned proper distance coding from tutors never fully recovered that ability, even with extensive practice. There’s a critical period, a window of development when certain skills must be learned or they’ll be permanently impaired.

This mirrors patterns in human development. Children who aren’t exposed to language during critical periods struggle to acquire full linguistic competence later. The parallel suggests that some aspects of cognitive development follow similar rules across vastly different species. The brain’s capacity for learning has inherent timing constraints that evolution has preserved across hundreds of millions of years of divergent evolution.

Honeybees and humans last shared a common ancestor over 400 million years ago, before life had even left the oceans. Any cognitive abilities we share aren’t inherited from that ancestor; they evolved independently. When bees and humans both show mental number lines, critical periods for learning, and symbolic reasoning, these represent convergent evolution of cognitive strategies. The same solutions keep emerging because they work.

The Bigger Picture

The cognitive abilities of bees challenge comfortable assumptions about the relationship between brain complexity and mental sophistication. We’ve long assumed that human-like cognition requires human-like brains. Bees suggest otherwise. Their tiny neural networks, running algorithms we’re only beginning to understand, accomplish feats that would have seemed impossible for insects just decades ago.

This has practical implications for artificial intelligence. If counting can be done with four neurons, and symbolic reasoning with a million, then current AI systems with billions of parameters may be wildly inefficient. Bee cognition offers a model of intelligence optimized for minimal resource use. Engineers building systems for drones, robots, and embedded devices are increasingly studying insect neural architectures for inspiration.

The findings also reframe questions about consciousness and subjective experience. If bees can count, learn symbols, understand abstract concepts like zero, and communicate through sophisticated dances, what is their inner life like? We have no way to access bee consciousness directly, but the complexity of their behavior suggests something more than mere stimulus-response machinery. The philosopher Thomas Nagel famously asked what it’s like to be a bat. The question might be even more interesting for bees.

For those interested in how other species communicate and think, research on crow intelligence reveals similar patterns of unexpected sophistication in small-brained creatures. And the discovery of underground tree communication networks suggests that complex information exchange may be far more widespread in nature than we assumed.

What bees teach us ultimately isn’t just about bees. It’s about intelligence itself: what it requires, how it emerges, and why it takes the forms it does. In their tiny brains, honeybees have evolved solutions to problems of navigation, communication, and quantity that human engineers are still struggling to replicate. The next time you see a bee hovering near a flower, consider that behind those compound eyes is a mind doing mathematics that took our species millennia to formalize. Small doesn’t mean simple. And the gap between human and animal minds may be smaller than our pride would prefer.