You’ve probably experienced it without knowing it had a name. Hours disappear while you’re absorbed in a project. Self-consciousness evaporates. The work flows through you as if you’re not quite doing it, as if you’ve become a conduit for something that wants to be made. When you finally look up, you’re surprised to find the room has grown dark and you’ve forgotten to eat.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called this experience “flow.” He spent his career studying it, interviewing thousands of people from artists to athletes to assembly line workers about the moments when they felt most alive. What he found challenged basic assumptions about happiness. The best moments in people’s lives weren’t passive or relaxing. They were the moments when body and mind were stretched to their limits in voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.

Flow theory has since influenced fields from sports psychology to game design, from education to workplace management. Understanding why certain activities produce flow, and how to cultivate it deliberately, offers something rare: a scientifically grounded path to more frequent experiences of deep satisfaction.

The Discovery

Csikszentmihalyi’s research began with a simple question: what makes people happy? He’d grown up in Hungary during World War II and its aftermath, watching his family lose everything and seeing neighbors succumb to despair. Some people, he noticed, maintained a sense of purpose and even joy despite terrible circumstances. Others with every material advantage seemed perpetually dissatisfied. What made the difference?

His method was unusual for psychology at the time. Instead of bringing subjects into laboratories, he developed the Experience Sampling Method, giving people pagers that beeped at random intervals throughout the day. When paged, subjects would record what they were doing, how they felt, and how engaged they were. This produced thousands of data points about happiness in natural contexts rather than artificial experimental settings.

The pattern that emerged was consistent across cultures, ages, and activities. The happiest moments weren’t when people were relaxing or consuming entertainment. They were when people were engaged in challenging activities that required skill, had clear goals, and provided immediate feedback. A surgeon performing a complex operation. A rock climber navigating a difficult route. A programmer solving an elegant problem. A musician improvising with full concentration. These activities produced what Csikszentmihalyi called “optimal experience,” and they shared a common structure.

The Anatomy of Flow

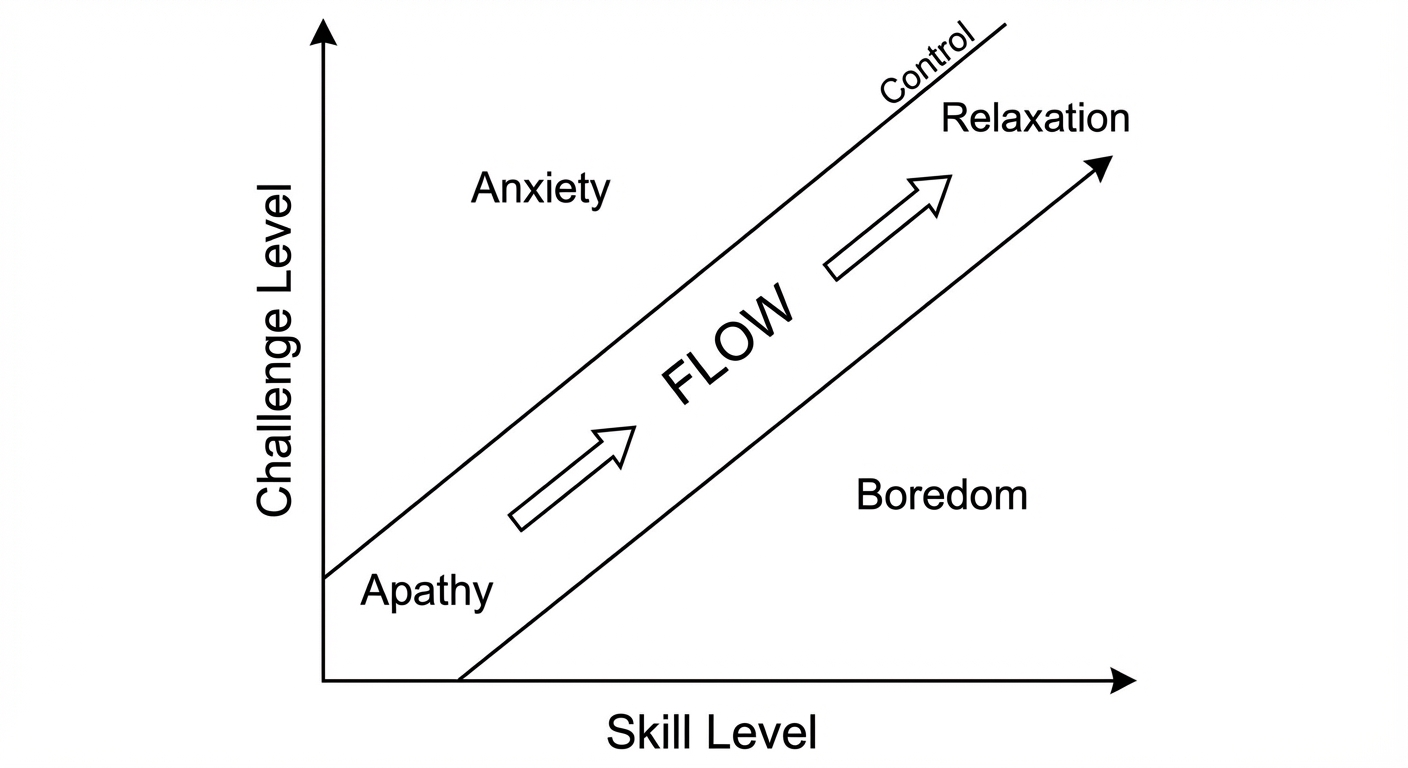

Flow experiences share several characteristics that distinguish them from ordinary consciousness. First, the activity must present challenges that roughly match one’s skills. Too easy, and boredom sets in. Too difficult, and anxiety takes over. Flow lives in the channel between, where the task is hard enough to require full attention but achievable enough to make progress feel possible.

Second, flow requires clear goals and immediate feedback. The rock climber knows exactly what she’s trying to do (reach the next hold) and knows instantly whether she’s succeeded. The surgeon can see whether the incision is clean, whether the bleeding is controlled. This tight feedback loop allows for constant adjustment and keeps attention focused on the present moment rather than wandering to past regrets or future worries.

Third, flow produces a merging of action and awareness. In ordinary consciousness, there’s a gap between the doer and the doing. We think about what we’re doing, evaluate it, second-guess ourselves. In flow, that gap closes. The activity becomes so absorbing that there’s no attention left over for self-reflection. The runner doesn’t think about running; she simply runs.

This merging produces flow’s most striking characteristic: the alteration of time perception. Hours pass in what feels like minutes. Alternatively, in high-stakes situations, seconds can stretch into what feels like ample time for complex decision-making. The normal sense of time, with its anxious awareness of deadlines and mortality, fades away. What remains is the eternal present of the activity itself.

Why Flow Feels Good

The neuroscience of flow is still being mapped, but researchers have identified several mechanisms that explain why these states feel so rewarding. During flow, the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which handles executive function, self-monitoring, and the inner critic, shows reduced activity. This “transient hypofrontality” quiets the voice that usually evaluates and second-guesses everything we do. Without that voice, we experience ourselves and our actions more directly.

Flow states also involve the release of several neurochemicals associated with pleasure and reward. Dopamine increases focus and motivation. Endorphins reduce pain and create mild euphoria. Norepinephrine enhances attention. Anandamide, the brain’s natural analog of marijuana’s active compound, promotes pattern recognition and lateral thinking. The neurochemical cocktail of flow is essentially the brain’s way of rewarding focused, skilled engagement.

This reward system probably evolved because flow-producing activities were often survival-relevant. The hunter tracking prey, the toolmaker crafting a weapon, the social strategist navigating complex group dynamics, all would have benefited from states of absorbed concentration. Flow may be the brain’s way of encouraging exactly the kinds of challenging, skill-building activities that helped our ancestors survive and thrive.

Cultivating Flow

The practical question is whether flow can be deliberately cultivated. Csikszentmihalyi believed it could, though not by directly pursuing the state itself. Flow is a byproduct of doing something well, not a goal to be achieved directly. The path to more flow runs through developing skills, seeking appropriate challenges, and structuring activities to provide clear goals and feedback.

One approach is to turn routine activities into flow experiences through what Csikszentmihalyi called “autotelic” engagement, doing things for their own sake rather than external rewards. A factory worker who challenges himself to optimize his movements, reduce errors, and beat his previous times can experience flow in work that might otherwise be mind-numbing. The activity itself hasn’t changed, but the mental framing has transformed it into a game with clear rules and achievable goals.

Another approach is to design environments and activities that naturally produce flow. Game designers are experts at this, carefully calibrating difficulty curves to keep players in the flow channel as their skills improve. Educators can apply similar principles, presenting material that challenges students just beyond their current abilities. Workplace designers can structure jobs to provide clearer goals, more immediate feedback, and greater autonomy in how tasks are completed.

The Bigger Picture

Flow theory offers a different perspective on the pursuit of happiness. Consumer culture tends to equate happiness with pleasure, with acquiring things and experiences that feel good passively. Csikszentmihalyi’s research suggests that the deepest satisfactions come from active engagement, from using our skills to meet challenges that matter to us.

This doesn’t mean passive pleasures are worthless. Rest and relaxation are necessary for well-being. But a life organized primarily around comfort and entertainment, around avoiding challenges and seeking ease, is likely to feel hollow. The happiest people in Csikszentmihalyi’s studies weren’t those with the most leisure time. They were those who found ways to engage fully with activities that stretched their abilities and aligned with their values.

Flow also offers a framework for thinking about meaning. The activities that produce flow tend to be ones we find meaningful, though the causation may run both ways. Perhaps we find activities meaningful precisely because they engage us fully, producing those moments when self-consciousness drops away and we feel most alive. Meaning and flow may be two descriptions of the same experience, viewed from different angles.

The ultimate implication is both simple and challenging: the good life is an engaged life. Happiness isn’t something we find; it’s something we create through the quality of our attention and the nature of our challenges. Flow is available in virtually any activity, if we approach it with the right mindset and appropriate skill. The moments that matter most aren’t the ones we consume but the ones we create.

Sources: Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s foundational flow research, Experience Sampling Method studies, neuroscience of optimal experience, applications of flow theory in education, sports psychology, and workplace design.