After every stock market crash, people emerge who claim they saw it coming. After every political upset, analysts appear who insist the outcome was obvious. After every relationship ends, friends say they always knew it wouldn’t work out. The pattern is so consistent it might seem like wisdom is common but ignored. More likely, it’s hindsight bias at work: our tendency to believe, after learning an outcome, that we would have predicted it.

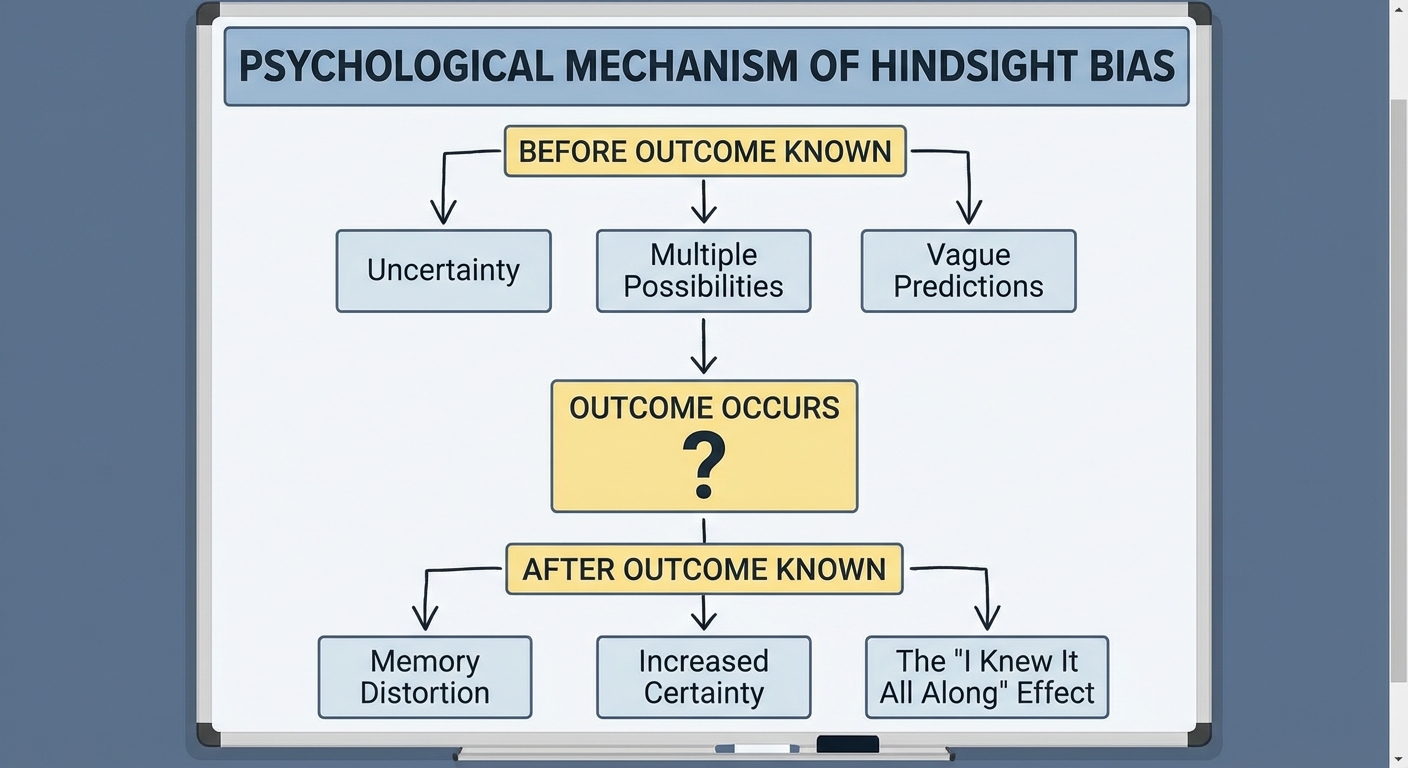

Hindsight bias is one of the most robust findings in psychology, replicated across cultures, ages, and domains of knowledge. When we learn how something turned out, our memory of what we expected subtly shifts to align with what actually happened. The past rearranges itself to make the present look inevitable. We don’t do this deliberately. The bias operates below conscious awareness, leaving us genuinely convinced that we knew all along.

Understanding hindsight bias matters because it distorts how we learn from experience, how we judge others’ decisions, and how we evaluate our own competence. The executive who made a risky bet that paid off looks like a visionary. The one who made an identical bet that failed looks reckless. In both cases, hindsight converts uncertainty into the illusion of predictability.

The Discovery

Psychologist Baruch Fischhoff first documented hindsight bias in the 1970s. His experiments were elegant. He would give participants historical scenarios and ask them to predict outcomes before revealing what actually happened. Other participants would be told the outcomes and asked to estimate what they would have predicted without that knowledge.

The results were striking. People who knew outcomes consistently overestimated how likely they would have judged those outcomes in advance. If told that a 19th-century military campaign succeeded, they rated success as predictable. If told the same campaign failed, they rated failure as predictable. The historical events hadn’t changed; only the participants’ knowledge had. Yet that knowledge transformed their perception of what had been foreseeable.

Fischhoff called this the “knew it all along” effect. Once we know what happened, it becomes difficult to reconstruct the genuine uncertainty that existed before. The outcome seems to follow inevitably from prior conditions, even when those conditions could have led to many different results. History appears more determined than it actually was.

The bias proved remarkably resistant to elimination. Even when participants were warned about hindsight bias and asked to correct for it, their estimates remained distorted. Knowing about the bias didn’t make people immune to it. The cognitive machinery that integrates new information with existing memories operates automatically, beyond the reach of conscious correction.

Why It Happens

Hindsight bias isn’t a bug; it’s a feature of how memory works. When we learn new information, we don’t store it in a separate compartment from what we already knew. Memory is reconstructive. Each time we recall something, we rebuild it from available pieces, and those pieces include everything we’ve learned since.

When you learn that a company went bankrupt, your memory of that company reorganizes around the bankruptcy. The warning signs become more salient. The optimistic projections seem foolish in retrospect. The narrative shifts to make the ending feel like the logical conclusion. This happens automatically, as the new information gets woven into your understanding of the past.

From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense. Our ancestors didn’t need accurate records of past uncertainty. They needed functional models of how the world works, updated with the latest information. Integrating outcomes into our understanding of what led to them creates useful causal models, even if it distorts our memory of what we actually knew at the time.

The problem is that accurate self-assessment requires remembering past uncertainty accurately. If you always feel like you knew what was going to happen, you can’t calibrate your actual predictive ability. Hindsight bias creates an illusion of understanding that may not reflect genuine skill at forecasting.

The Consequences

Hindsight bias has practical consequences across many domains. In medicine, doctors may underestimate how difficult a diagnosis was once they know what the patient had. A condition that seems obvious in retrospect may have presented ambiguously, with symptoms that could have indicated several diseases. Hindsight makes the correct diagnosis seem more apparent than it was, leading to unfair judgments of doctors who pursued different possibilities.

In business and finance, hindsight bias distorts how we evaluate decisions. A strategic choice that turned out well looks brilliant; the same choice that turned out poorly looks foolish. But the decision-maker faced uncertainty at the time. Good process doesn’t guarantee good outcomes, and bad outcomes don’t prove bad process. Hindsight bias collapses this distinction, judging decisions entirely by their results.

In personal relationships, hindsight bias can breed resentment. After a relationship fails, everything that happened gets reinterpreted as signs of eventual failure. Happy memories get recast as delusions or denials. The genuine uncertainty about how things would turn out, the hope that was rational at the time, gets overwritten by the knowledge of how things ended.

Most perniciously, hindsight bias affects how we learn from experience. If we always feel like outcomes were predictable, we miss opportunities to update our mental models. The proper lesson from a surprising event might be that the world is less predictable than we thought. Hindsight bias converts that lesson into the opposite: the event wasn’t really surprising; we just weren’t paying attention.

Fighting the Bias

Given that hindsight bias resists conscious correction, how can we reduce its effects? The most reliable strategy involves creating records before outcomes are known. Keeping a decision journal that documents expectations, reasoning, and uncertainty estimates provides an external check against memory’s tendency to revise itself.

Organizations can institutionalize similar practices. Pre-mortems, where teams imagine that a project has failed and work backward to identify what might have caused the failure, force consideration of uncertainty before outcomes are known. Formal forecasting with tracked predictions allows calibration of actual predictive accuracy rather than remembered accuracy.

When evaluating others’ decisions, the discipline of asking “what did they know at the time?” can partially counteract hindsight bias. This requires deliberate effort to reconstruct the state of uncertainty that existed before the outcome was known. It’s difficult, but it’s more fair than judging historical decisions by standards that only became clear later.

The Bigger Picture

Hindsight bias reveals something fundamental about how we understand the world. We prefer narratives where causes lead clearly to effects, where what happened is what had to happen. Randomness and genuine uncertainty are psychologically uncomfortable. We’re pattern-seekers who find patterns even when none exist, narrators who construct stories even when reality was messier than any story can capture.

The “knew it all along” feeling isn’t dishonesty or even arrogance. It’s how human memory works, optimized for functionality rather than accuracy, for useful models rather than faithful recordings. Understanding this doesn’t eliminate the bias, but it can make us more humble about our remembered predictions and more generous in judging others who faced uncertainty we no longer feel.

The next time you’re tempted to say you saw something coming, consider whether that certainty existed before the event or only emerged afterward. The answer might be uncomfortable, but it’s probably closer to the truth.

Sources: Baruch Fischhoff’s foundational hindsight bias research, cognitive psychology of memory reconstruction, decision-making under uncertainty studies, organizational behavior research on judgment and evaluation.