Nearly six miles below the ocean surface, in crushing darkness at pressures that would instantly kill a human, life persists. Scientists recently confirmed the existence of an ecosystem thriving in conditions previously thought impossible for complex life, a community of organisms that has never seen sunlight and never will, surviving on chemical energy from the planet itself.

The discovery pushes the boundaries of the known biosphere deeper than ever before. We knew life could survive at great depths, but the newly documented ecosystem exists in an environment so extreme that it forces us to reconsider what limits biology can overcome. The organisms there face pressures over a thousand times greater than at sea level, temperatures ranging from near-freezing to hundreds of degrees at hydrothermal vents, and complete absence of the photosynthesis-derived energy that powers virtually all surface life.

If life can flourish in conditions this hostile on Earth, the implications extend beyond our planet. Every discovery of life in an extreme environment expands the range of conditions where we might find life elsewhere. The moons of Jupiter and Saturn, with their subsurface oceans and possible hydrothermal activity, suddenly look more promising as potential habitats.

The Hadal Zone

Oceanographers divide the deep sea into zones based on depth. The hadal zone, named like the geological Hadean after Hades, begins at about 6,000 meters (roughly 3.7 miles) and extends to the bottom of the deepest trenches. Before the recent discoveries, scientists knew life existed in the hadal zone, but mostly as sparse populations of scavengers feeding on organic matter that drifts down from above.

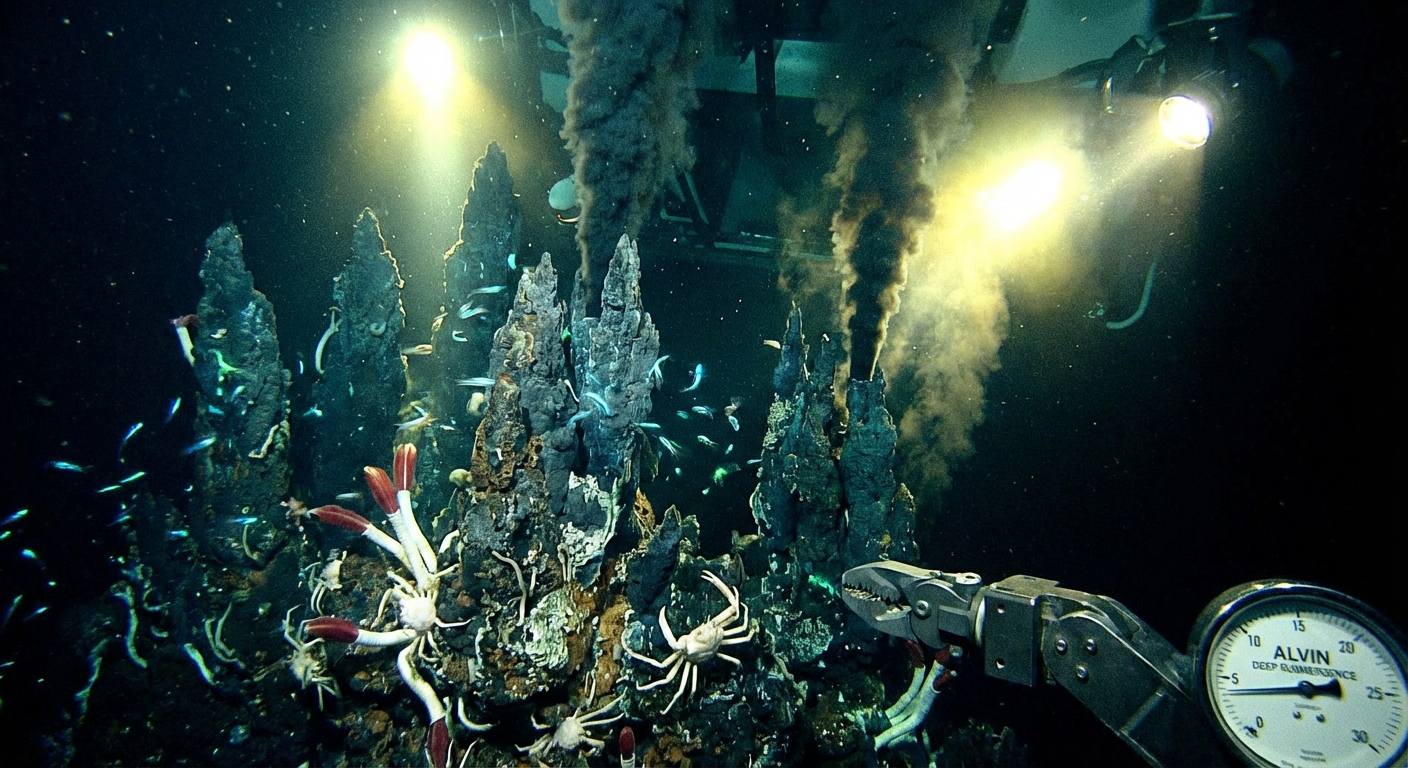

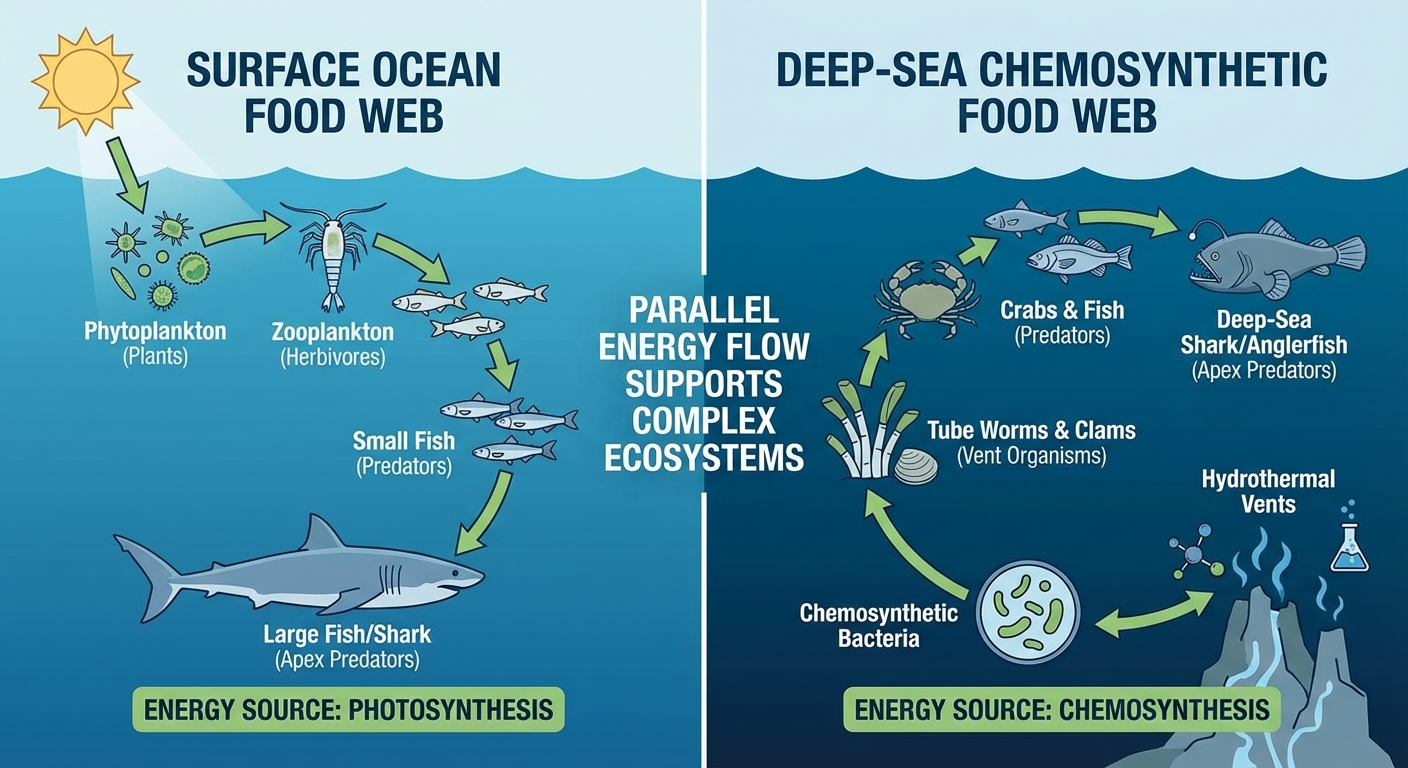

The newly discovered ecosystem is different. Instead of depending on the surface, it runs on chemosynthesis, the process of deriving energy from chemical reactions rather than sunlight. At hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean trenches, superheated water laden with hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other chemicals emerges from the seafloor. Specialized bacteria can harvest energy from these chemicals, forming the base of a food web completely independent of photosynthesis.

Chemosynthetic ecosystems were first discovered at hydrothermal vents in 1977, revolutionizing our understanding of where life could exist. But those original discoveries were at depths of around 2,500 meters. The new ecosystem sits nearly four times deeper, in conditions significantly more extreme.

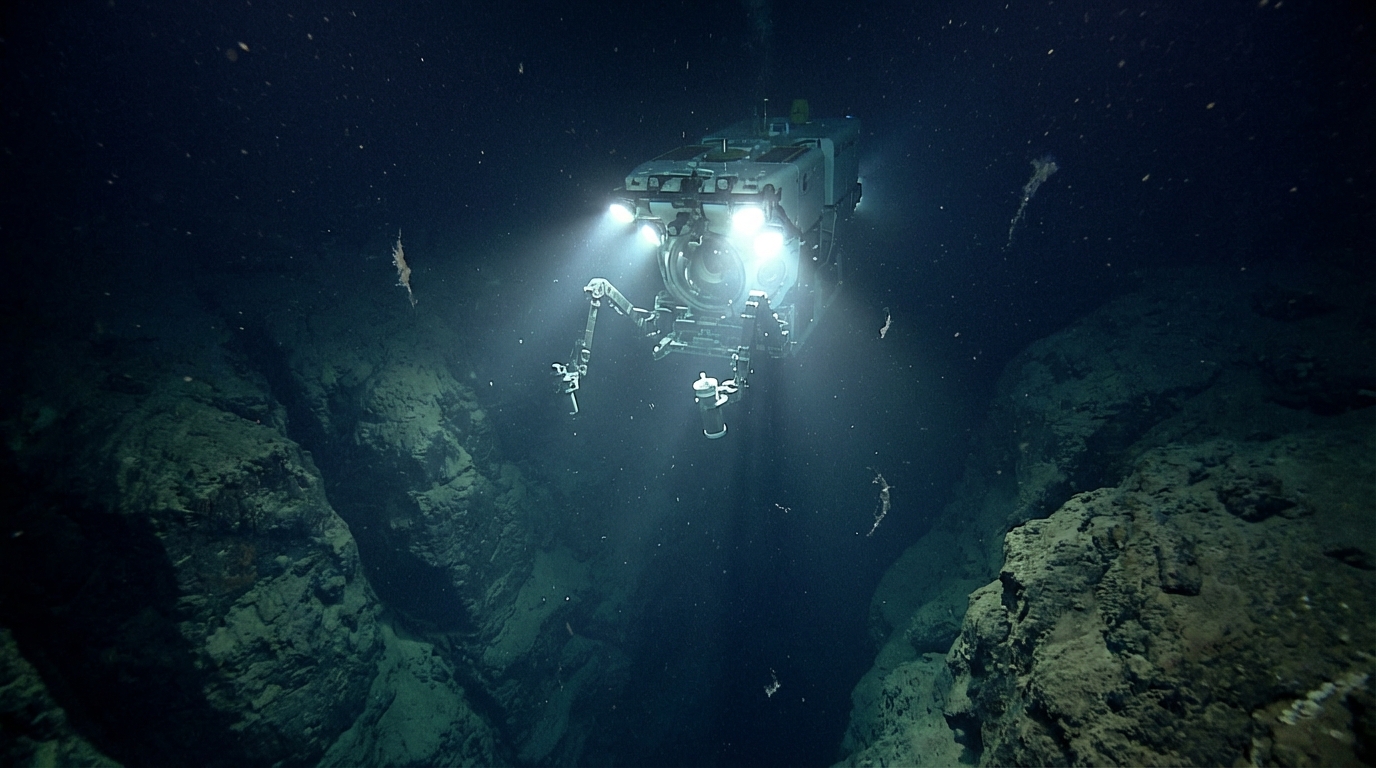

The pressure at these depths is staggering. Every 10 meters of water depth adds roughly one atmosphere of pressure. At nearly 10,000 meters, the pressure exceeds 1,000 atmospheres. Specialized equipment must be built to withstand forces that would collapse ordinary submersibles like soda cans. The organisms living there have evolved proteins and cell membranes that function under these conditions, biochemistry adapted to environments that would destroy surface life.

What Lives There

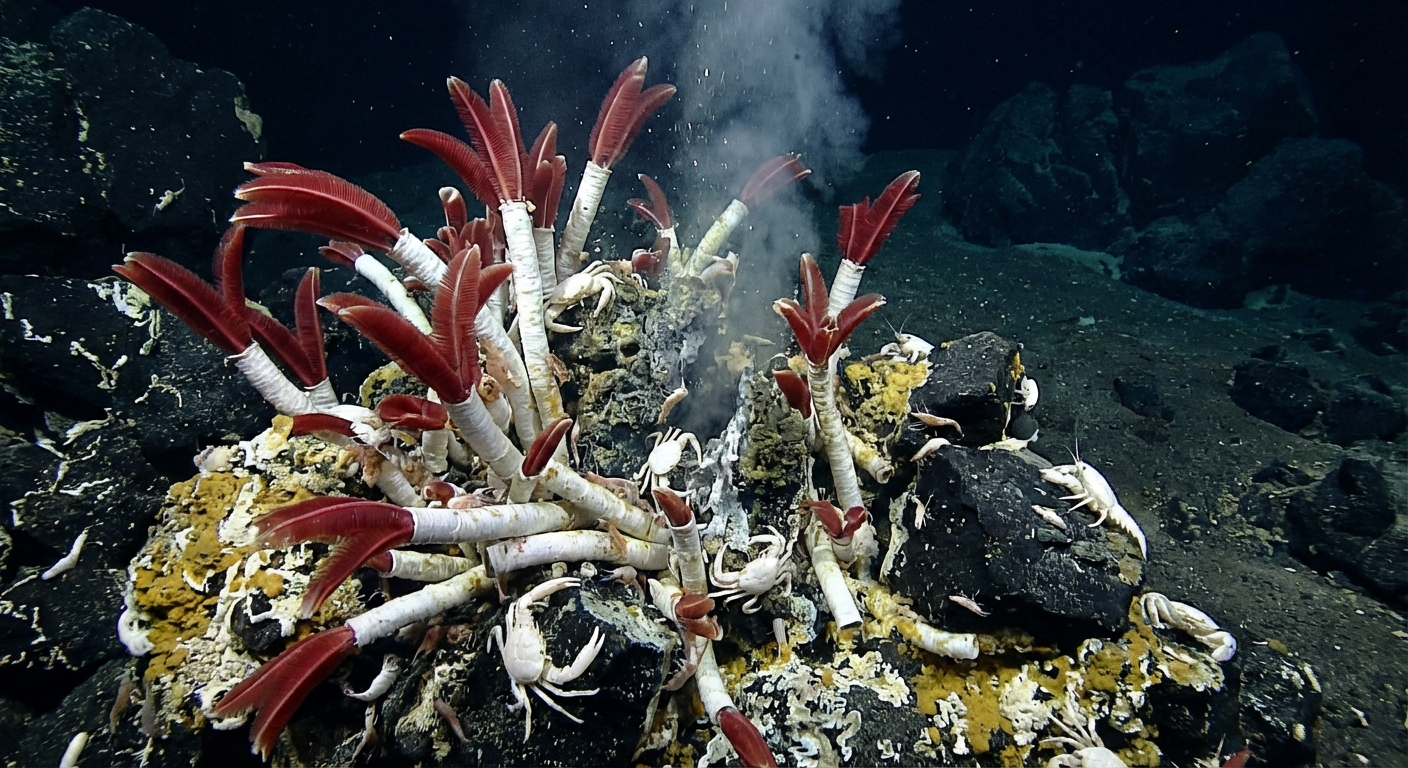

The deep ecosystem centers around hydrothermal vent systems that pump mineral-rich water into the surrounding ocean. Around these vents, mats of chemosynthetic bacteria form the foundation of the food web. These bacteria are ancient, members of lineages that may have originated billions of years ago when the entire surface of Earth was hostile to life.

The bacteria support communities of other organisms. Specialized worms, crustaceans, and mollusks cluster around the vents, grazing on bacterial mats or filtering particles from the water. Predators prey on these primary consumers. Scavengers clean up organic debris. The ecosystem has all the functional elements of surface ecosystems, just operating on chemical rather than solar energy.

What makes the newly discovered ecosystem remarkable isn’t just its depth but its isolation. The organisms there have been cut off from the surface for millions of years, possibly longer. They’ve evolved independently, developing unique adaptations to their extreme environment. Some of the species found may exist nowhere else on Earth, endemic to a habitat the size of a few football fields at the bottom of an oceanic trench.

This isolation has implications for how we think about life’s diversity. The total biomass in these deep ecosystems is small compared to surface environments, but the evolutionary innovation may be disproportionately large. Extreme environments push biology to its limits, forcing adaptations that reveal what’s biologically possible.

Energy From Below

The most striking aspect of deep chemosynthetic ecosystems is their independence from the sun. Every ecosystem you’ve ever seen, every forest, coral reef, and grassland, ultimately depends on photosynthesis. Even deep-sea scavengers typically eat organic matter that originated at the surface, making them indirectly dependent on sunlight.

Chemosynthetic ecosystems break this dependency. Their energy comes from the Earth itself, from heat generated by radioactive decay in the planet’s interior, from chemical reactions between water and rock. If the sun disappeared tomorrow, surface life would die within weeks or months. Deep chemosynthetic ecosystems might barely notice.

This has profound implications for where we might find life elsewhere in the solar system. For decades, the search for extraterrestrial life focused on finding conditions similar to Earth’s surface: liquid water, moderate temperatures, and access to sunlight. Deep chemosynthetic ecosystems suggest that life might exist anywhere with liquid water and chemical energy, even in places that never see a ray of sunlight.

Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus both have subsurface oceans heated by tidal forces. If hydrothermal vents exist on their ocean floors, they might support life similar to Earth’s deep-sea communities. The discovery of increasingly extreme ecosystems on our own planet makes this possibility harder to dismiss.

The Bigger Picture

The deepest ecosystem yet discovered is a reminder of how little we know about our own planet. The deep ocean remains less explored than the surface of the Moon. Vast areas have never been surveyed at all. The organisms living in the deepest trenches were unknown until we developed the technology to reach them, and even now, our understanding is fragmentary.

Each new discovery extends the known boundaries of life. Organisms have been found thriving in Antarctic ice, in boiling hot springs, in radioactive waste pools, and now in the crushing depths of oceanic trenches. The biosphere isn’t confined to the comfortable surface conditions where humans live. It extends into environments we once assumed were sterile.

This expanding understanding of life’s range changes how we think about our planet and potentially about the universe. Earth isn’t just inhabited at the surface; it’s inhabited through a thick layer of crust, ocean, and atmosphere. Life has infiltrated nearly every environment that offers even a minimal foothold. The deepest ecosystem is just the latest example of biology’s remarkable ability to find a way.

Sources: Deep-sea exploration expeditions, chemosynthetic ecosystem research, hadal zone biology studies, astrobiology research on life in extreme environments, hydrothermal vent community ecology.