Deep within a dark German cave, researchers set up night-vision cameras expecting to document bat behavior. What they captured instead upended decades of assumptions about one of the world’s most familiar animals. The footage showed brown rats standing upright on their hind legs, reaching into the air, and snatching bats out of mid-flight. Then they ate them.

Scientists at the Natural History Museum in Berlin recorded this behavior repeatedly over multiple observation sessions. The rats weren’t scavenging dead or injured bats, and they weren’t catching them on the ground. They were actively hunting flying mammals, displaying a level of predatory sophistication that nobody expected from a species we thought we understood completely.

The discovery, published in late 2025, belongs to a growing collection of findings that have forced biologists to reconsider what common animals are actually capable of. Rats, it turns out, have been hiding behaviors in plain sight, waiting for researchers with the right technology to finally witness what they do when humans aren’t watching.

What the Cameras Revealed

The research team initially installed cameras in abandoned mine shafts and natural cave systems in Germany to study bat colony dynamics. Brown rats, which are common around human settlements but also inhabit wild areas, had been noted in these caves before, but nobody considered them particularly interesting in this context. They were assumed to be scavenging food scraps or seeking shelter.

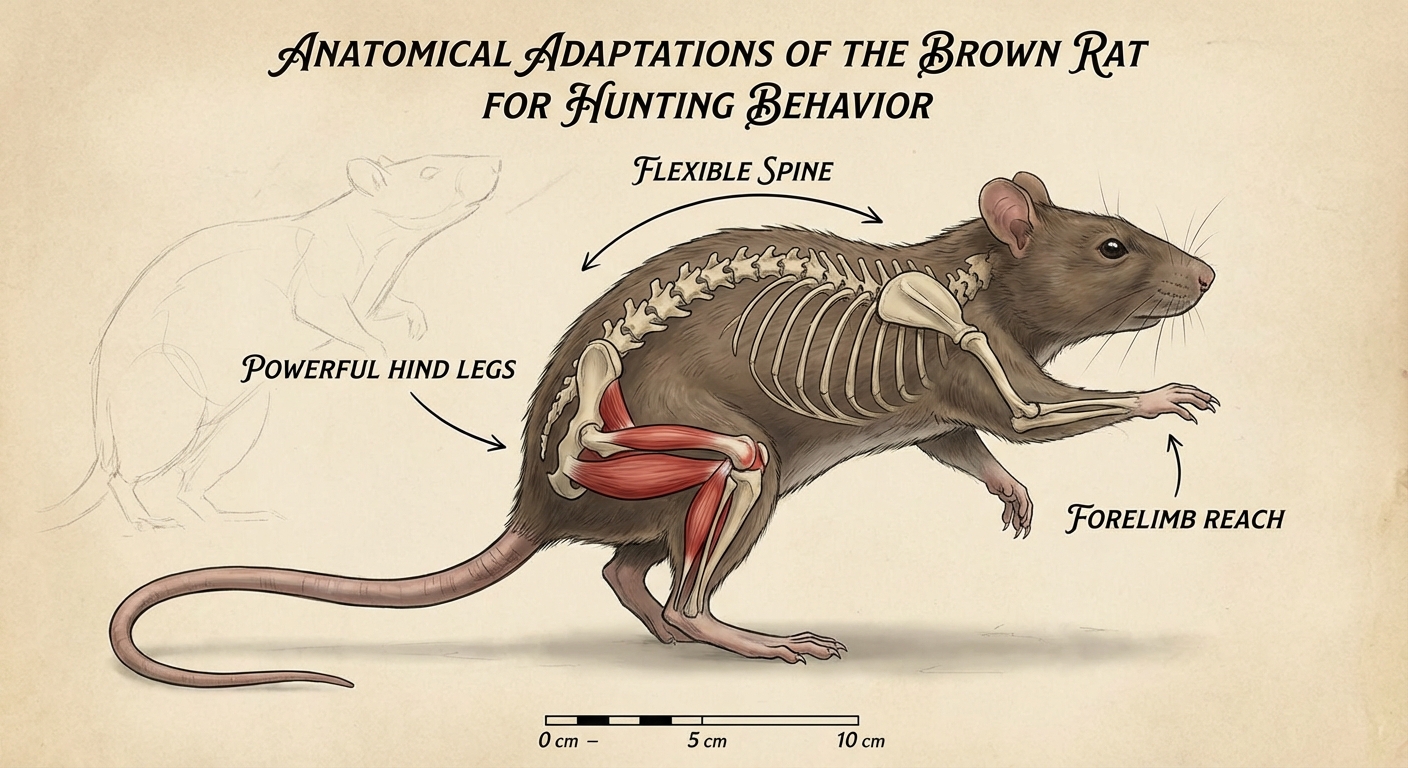

The footage told a different story. Rats were observed positioning themselves at known flight paths where bats entered or exited roosts. When bats flew within reach, the rats would rise onto their hind legs, a posture they can maintain for extended periods, and strike upward with their forelimbs. The success rate wasn’t high, but it didn’t need to be. A single bat represents a significant caloric payoff for a rat.

What struck researchers most was the apparent sophistication of the hunting strategy. The rats weren’t lunging randomly at passing bats. They positioned themselves strategically, waited with apparent patience, and struck at optimal moments. Some individuals appeared to have learned particularly productive spots and returned to them repeatedly.

This isn’t the kind of behavior you develop accidentally. It suggests that these rats, or their ancestors, discovered through trial and error that bats were catchable, and then refined their technique over generations. It also suggests that this behavior might be far more common than the German observations indicate, simply because nobody had ever thought to look for it.

Rewriting the Rat Rulebook

The discovery challenges fundamental assumptions about rat ecology. Standard textbooks describe rats as omnivorous scavengers that occasionally prey on slow-moving or defenseless animals: eggs, nestlings, insects, and the like. Active predation of flying vertebrates falls so far outside the expected behavioral range that researchers initially wondered if they were observing aberrant individuals or unusual circumstances.

But follow-up analysis suggests otherwise. The behavior was observed across multiple individuals of different ages and sexes. It occurred over an extended observation period, ruling out a single unusual event. And preliminary surveys of other cave sites with rat populations have found similar evidence, though less extensively documented.

This matters beyond the specific case of rats and bats because it demonstrates how much we still don’t know about even the most studied species. Rattus norvegicus, the brown rat, has lived alongside humans for millennia. It’s one of the most important model organisms in medical research. We have mapped its genome, studied its neurology, and observed its behavior in countless laboratory settings. And yet it was exhibiting a completely undocumented hunting strategy in the wild.

The lesson is humility. If rats can surprise us, so can virtually any animal. The behaviors we observe in controlled settings, or during brief field observations, may represent only a fraction of what species are actually doing.

How Other Animals Compare

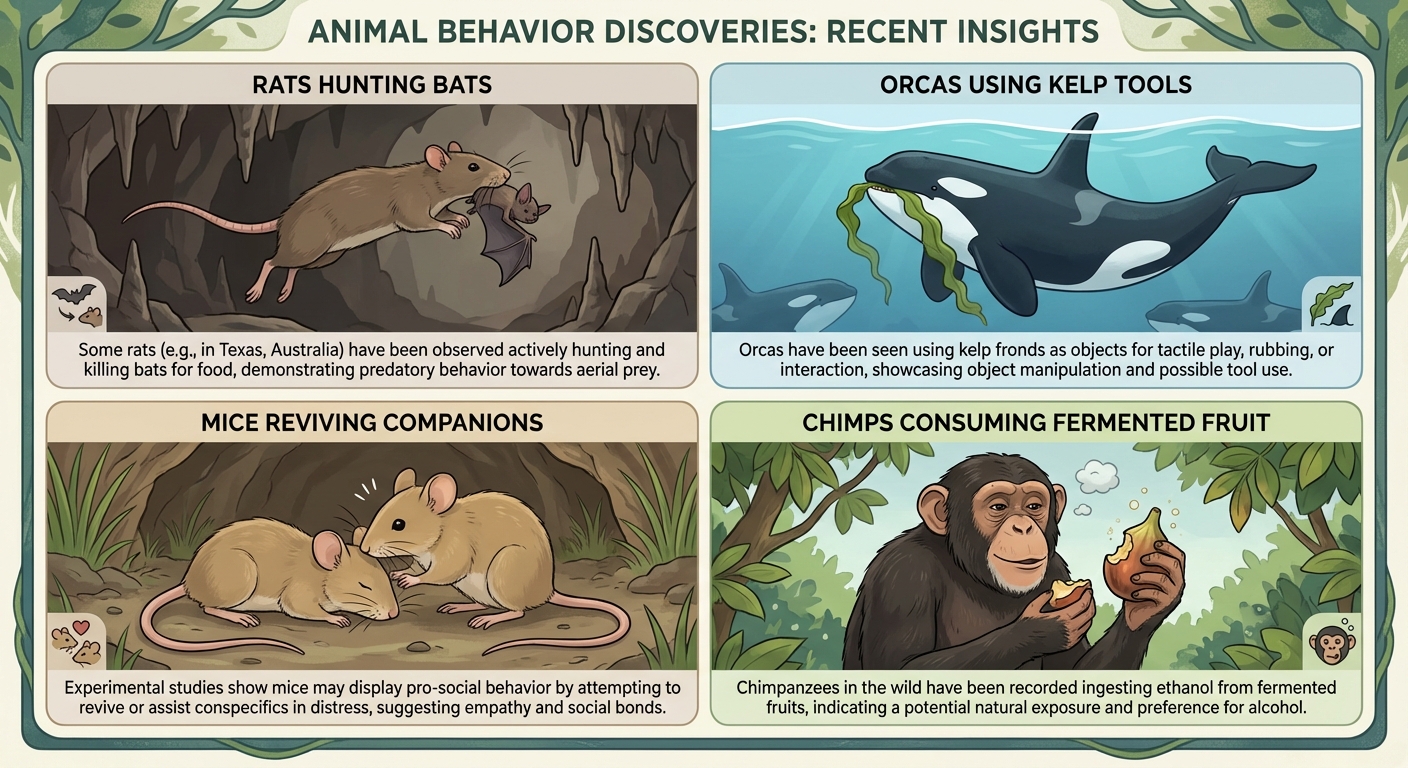

The rat discovery joins a remarkable year for unexpected animal behavior findings. In separate research, scientists documented orcas creating and using kelp as grooming tools, sharing these “loofahs” with other individuals in what researchers termed “allokelping.” Mice were observed attempting to revive unconscious companions, pawing and nipping at anesthetized cage-mates as if trying to wake them up. Chimpanzees, it turned out, naturally consume significant amounts of alcohol from fermenting fruit, enough to equal one or two human drinks daily.

Each of these discoveries shares a common element: animals doing things we assumed they couldn’t or wouldn’t do. The orca findings suggest cultural transmission of tool use in marine mammals. The mouse observations hint at something that might be called empathy, or at least a response to distress, in a species often treated as having minimal emotional complexity. The chimpanzee research reframes our understanding of alcohol’s role in primate evolution.

Together, these findings suggest that the behavioral diversity of the animal kingdom is far greater than our current scientific understanding captures. Animals are not simply executing fixed genetic programs. They’re learning, adapting, innovating, and transmitting knowledge in ways that mirror, at least superficially, human cultural evolution.

Why We’re Only Seeing This Now

The obvious question is why these behaviors went unnoticed for so long. The answer involves both technology and attention.

Camera technology has transformed wildlife observation. Night-vision and infrared cameras can now operate autonomously for months, capturing behaviors that occur rarely, at night, or in locations where human presence would disrupt normal activity. The rat-bat hunting was invisible to direct observation not because rats hid the behavior, but because they did it in dark caves when nobody was watching.

Storage and analysis capabilities matter too. A single camera can generate thousands of hours of footage over an extended deployment. Reviewing all that footage manually would be prohibitively labor-intensive. Machine learning algorithms that can flag unusual behaviors for human review have made it practical to process the massive datasets that modern field studies generate.

But technology alone doesn’t explain the discoveries. The German researchers weren’t looking for rat predation; they were studying bats. The unexpected finding emerged because they were paying attention to everything in the footage, not just their primary research subjects. Scientific breakthroughs often come from noticing what you weren’t looking for.

There’s also a cultural shift in how biologists think about animal cognition and behavior. For most of the twentieth century, researchers were trained to avoid attributing complex mental states to animals, a principle called “Morgan’s Canon” after the nineteenth-century psychologist who articulated it. This was a reasonable guard against anthropomorphism, but it may have led scientists to underestimate what animals were actually doing, dismissing complex behaviors as instinct rather than investigating them as potential examples of learning, planning, or innovation.

The Bigger Picture

The image of a rat snatching a bat from the air is arresting precisely because it violates our mental categories. Rats scavenge; they don’t hunt. Bats fly; they’re not prey for grounded mammals. The behavior crosses boundaries we assumed were fixed.

But nature doesn’t respect our categories. Evolution rewards whatever works, regardless of whether it fits neatly into a textbook description of a species’ ecological niche. The rats that figured out how to catch bats gained access to a rich food source that other rats couldn’t exploit. Their descendants inherited whatever combination of anatomy, neurology, and learning ability made that possible. Over generations, a novel behavior became established.

This is how ecological niches expand and how species relationships evolve. It’s also a reminder that the natural world remains full of surprises for anyone willing to look carefully. The rats were always hunting bats. We just needed the right cameras, the right locations, and the right willingness to accept what we were seeing.

The next time you see a rat scurrying along an urban alley, consider that it might be capable of far more than you imagine. The animal kingdom’s true behavioral diversity is likely far stranger and more wonderful than our current catalogs suggest. We’re only beginning to glimpse what’s really out there.