On the final day of 2025, consider this: scientists have formally described approximately 2.1 million species on Earth. They estimate the actual number is somewhere between 8 and 12 million. This means we have cataloged, at best, a quarter of the life forms sharing our planet. And the gap is closing faster than you might expect. Each year, researchers identify more than 16,000 species previously unknown to science, a rate that has accelerated even as extinction threatens to erase species before they can be found.

The scale of ongoing discovery contradicts a common assumption that we have already found everything important. The great age of exploration, when naturalists returned from distant lands with specimens of bizarre and wonderful creatures, is often portrayed as complete. But the truth is different. We are still in the midst of that exploration, still filling in a picture of planetary life that remains mostly blank.

The Discovery Machine

The mechanics of species discovery are less romantic than Victorian exploration but no less productive. New species emerge from three main sources: field expeditions to under-sampled regions, museum collections that contain specimens never properly studied, and new analytical techniques that reveal hidden diversity.

Field work remains essential. Remote rainforests, deep ocean trenches, and isolated islands continue to yield organisms that science has never seen. In 2025, researchers announced numerous species from these environments: new pikas from the Himalayas, lanternsharks from Australian waters, river turtles from the Amazon basin. Each expedition returns with specimens that take years to fully analyze and describe.

But perhaps surprisingly, many discoveries happen in museums rather than jungles. The great natural history museums of the world contain millions of specimens collected over centuries. Many were deposited in drawers and never carefully examined. Modern researchers, armed with better microscopes and genetic tools, regularly discover that specimens labeled as one species are actually several distinct species, or that obscure specimens represent lineages never formally described.

Genetic analysis has revolutionized this process. DNA sequencing reveals differences invisible to the naked eye. Creatures that look identical may turn out to be genetically distinct, having diverged millions of years ago. This hidden diversity is particularly common in invertebrates, fungi, and microbes, groups where physical appearance is less variable than in mammals and birds.

What We Are Finding

The 16,000-plus species described each year span all major groups of life, but the distribution is uneven. Insects and other arthropods account for the largest share, reflecting both their genuine diversity and the relative lack of attention they have received historically. Beetles alone may comprise a quarter of all animal species, and most beetle species remain undescribed.

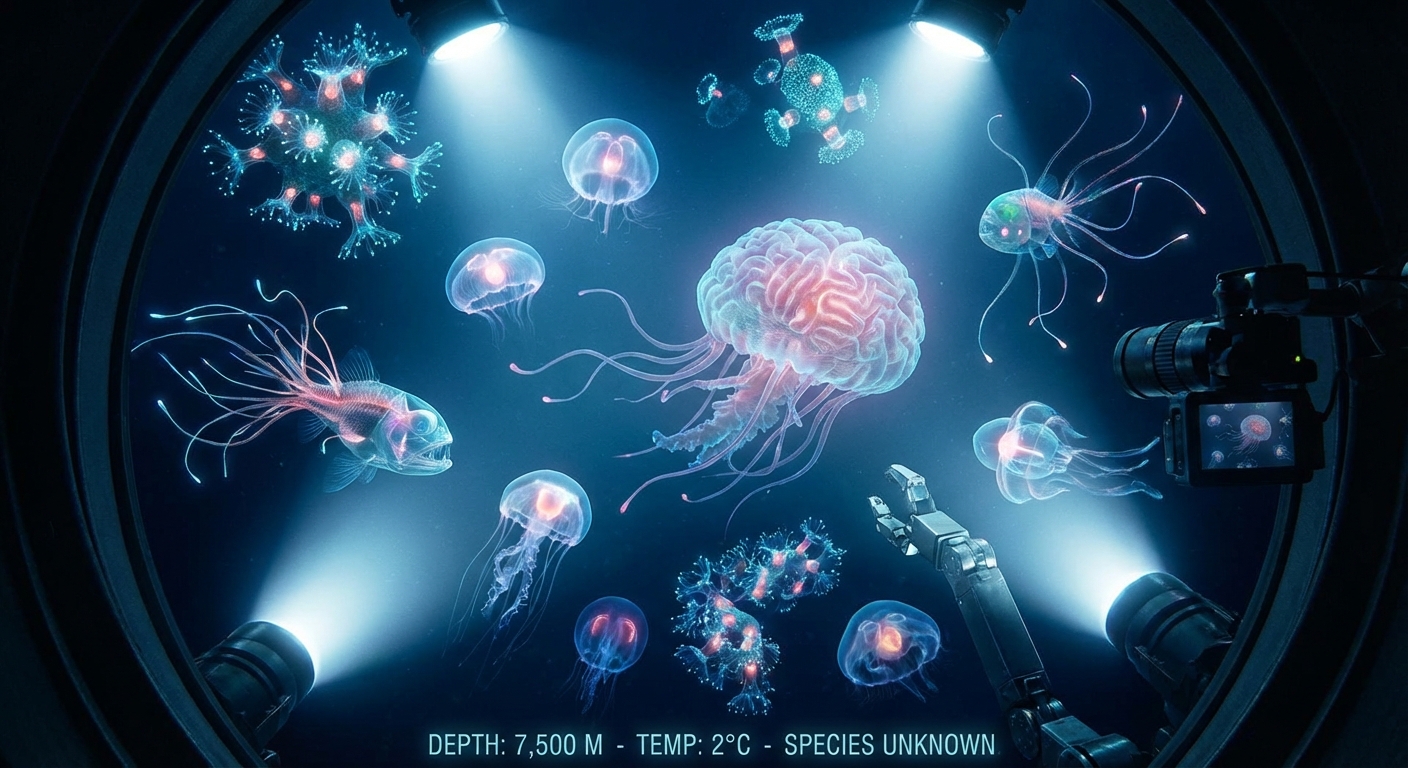

Flowering plants, fungi, and marine invertebrates also contribute heavily to annual totals. These groups are diverse, often small-bodied, and found in habitats that have not been thoroughly surveyed. The deep ocean, in particular, is almost entirely unexplored. Every submersible dive to abyssal depths seems to encounter organisms unknown to science.

Vertebrates, the group that includes mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, contribute fewer new species but still surprise. New frogs and fish are described regularly. Even mammals and birds, the most thoroughly studied groups, occasionally yield new species. In many cases, these new vertebrates are found not in remote wildernesses but in populated regions where local people have known about them for generations.

The distribution of new discoveries is also geographically uneven. Tropical regions, particularly rainforests, continue to yield the most new species. But discoveries occur everywhere, including in temperate zones and even in well-studied regions like Europe and North America. The lesson is that unexplored corners exist closer to home than we might imagine.

Racing Against Extinction

The ongoing pace of discovery creates a strange tension with conservation. On one hand, the fact that we are still finding so many species suggests Earth’s biodiversity is even richer than appreciated. On the other hand, many newly described species are already endangered, known from only a handful of specimens or a single location.

Some species are described only after they have gone extinct. Researchers study old collections and realize that a specimen collected decades ago represents a species never seen again. These posthumous descriptions are increasingly common, a grim reflection of habitat destruction and climate change eliminating species before science can document them.

The implication is sobering. We are in a race against time, trying to catalog Earth’s biodiversity even as that biodiversity shrinks. Every species lost before discovery is knowledge erased. We will never know how many species have vanished without leaving any trace, not even a specimen in a museum drawer.

Conservation priorities must grapple with this uncertainty. It is difficult to protect species that have not been described, located in habitats we have not surveyed. The areas with the highest discovery rates, tropical rainforests and deep oceans, are also under the most intense pressure from human activities. Protecting these regions protects not just known species but the unknown ones waiting to be found.

The Taxonomic Crisis

Despite the importance of species discovery, the field of taxonomy, the science of identifying and classifying species, faces a crisis. The number of working taxonomists has declined for decades as funding shifted to molecular biology, genetics, and other fields seen as more cutting-edge. Many taxonomists are nearing retirement with few young scientists trained to replace them.

This creates a bottleneck. Thousands of specimens sit in museums waiting for expert attention that may never come. New species are collected in the field but remain undescribed because no one has the expertise or time to study them. The backlog grows even as the rate of new collection accelerates.

Efforts are underway to address this crisis. DNA barcoding and other automated techniques can speed preliminary identification. Citizen science projects enlist volunteers to help process specimens. International collaborations spread the work across more institutions. But these measures are not keeping pace with the need. Without more taxonomists, the catalog of life will remain incomplete even as species vanish.

Why Discovery Matters

Why does it matter how many species exist? At one level, the question is scientific. Understanding life on Earth is a fundamental goal of biology, and species are the basic units of that understanding. Each species represents a distinct evolutionary lineage with unique genetic information, ecological relationships, and potential value.

At another level, the question is practical. Many species have proven useful to humans: sources of medicines, models for research, agents of pest control or pollination. The undiscovered species of today may be the critical resources of tomorrow. When species go extinct before being studied, those potential benefits are lost forever.

But perhaps the deepest reason to care about species discovery is what it says about our place in the world. We share this planet with millions of other life forms, most of which we have never met. That ongoing discovery is possible, that surprises await in the next forest or the next museum drawer, means we have not exhausted the wonder of the natural world. There is more here than we know.

The Bigger Picture

The pace of species discovery in 2025 and beyond tells a story of Earth’s abundance and our incomplete knowledge of it. We are not at the end of exploration but in the middle. The catalog of life is a work in progress, filled in by thousands of researchers and countless expeditions and analyses, still far from complete.

This should inspire both humility and urgency. Humility because we cannot claim to understand ecosystems when we have not identified their components. Urgency because the window for discovery is closing. Climate change, habitat destruction, and pollution are erasing species faster than we can find them.

On the last day of 2025, somewhere in the world, a scientist is describing a species no one has described before. In a museum collection, a specimen is being recognized as something new. On a research vessel, a net is bringing up creatures from depths where no human eye has ever looked. The work continues, as it must, for as long as there are species to find and people with the curiosity to find them.

The 16,000 species described this year join the great inventory of life, a project begun by Aristotle and Linnaeus, carried forward by Darwin and Wallace, and continued by researchers around the world today. It is one of humanity’s grandest endeavors, the attempt to know what lives on our planet. And it is far from finished.