If you lose an eye, it’s gone forever. Human eyes don’t regenerate. Neither do the eyes of most animals. The complex structures of lens, retina, and optic nerve that allow us to see develop once during embryonic growth and never rebuild themselves afterward. Eye injuries in humans are permanent disabilities.

Golden apple snails play by different rules. These freshwater mollusks, native to South America and now invasive across Asia, can lose an entire eye and regrow it within a month. The new eye isn’t a simplified replacement; it’s a complete, functional organ with all the structures of the original. The snail sees through it as well as it saw through the eye it lost.

Scientists have now identified genes involved in this remarkable process, raising possibilities that extend far beyond mollusk biology. If we can understand how snails regenerate complex sensory organs, we might eventually apply those principles to help humans recover from eye injuries. The gap between snail and human is vast, but evolution has already solved problems that medical science is still struggling with.

Eyes Like Ours

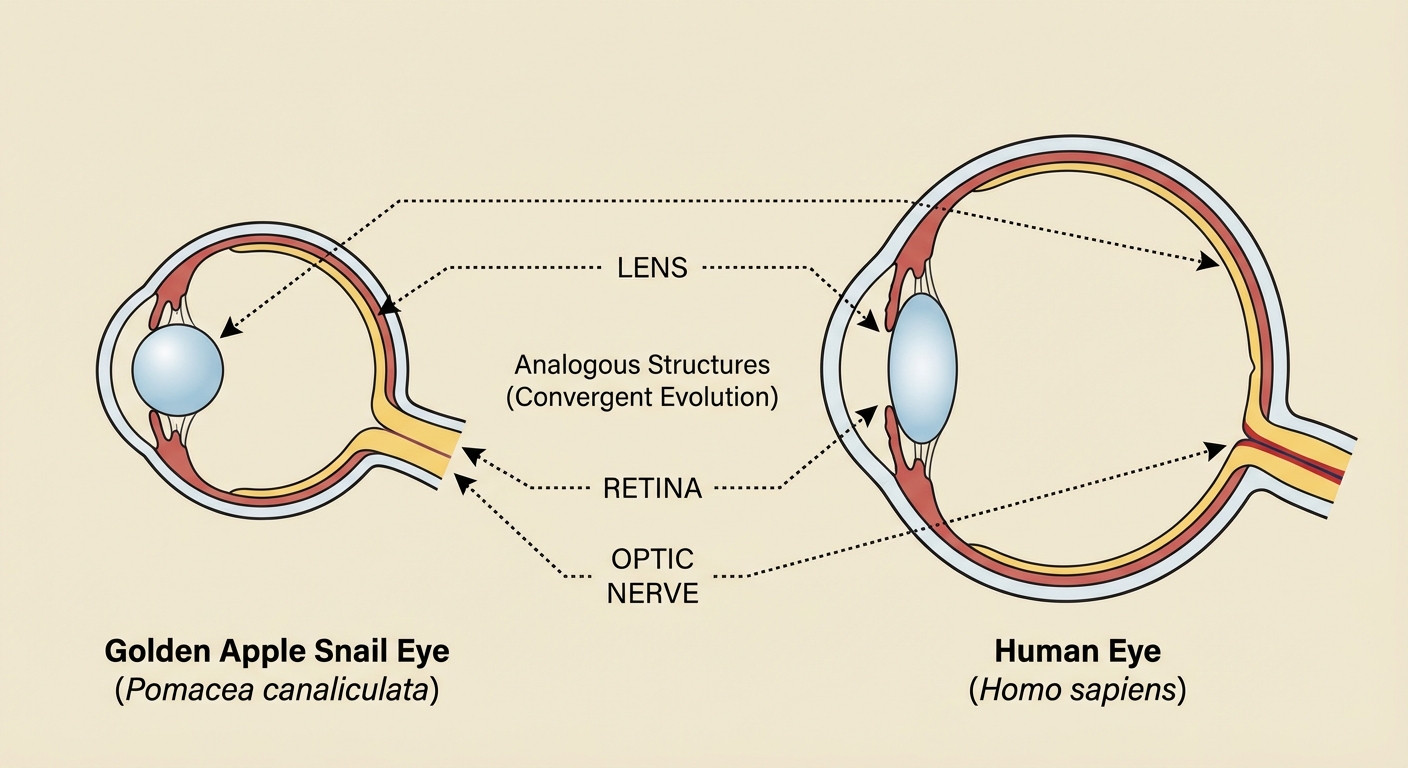

What makes the golden apple snail’s regenerative ability particularly interesting is that its eyes are structurally similar to vertebrate eyes. The snail has what’s called a camera-type eye: a single lens that focuses light onto a retina, which converts the light into neural signals. This is the same basic design as human eyes, evolved independently in mollusks and vertebrates.

Most invertebrates have compound eyes, like insects, or simple light-sensing organs that can detect brightness but not form images. Camera eyes are relatively rare outside of vertebrates, appearing only in some cephalopods (squids and octopuses) and a few snail species. The golden apple snail’s eyes can form actual images, allowing the snail to navigate its environment, avoid predators, and find food.

This structural similarity is the result of convergent evolution: unrelated organisms independently evolving similar solutions to the same problem. Eyes have evolved independently dozens of times across the tree of life. Each time, natural selection refined light-sensitive cells into increasingly complex organs. The camera eye represents a particularly sophisticated endpoint, and it’s emerged in both mollusks and vertebrates despite their distant evolutionary relationship.

The convergence makes regeneration research more relevant to humans. A snail’s eye isn’t identical to ours, but it faces many of the same developmental challenges. It must build a transparent lens, organize photoreceptor cells into a functional retina, and connect everything to the nervous system. Understanding how snails accomplish this reconstruction may reveal principles applicable to vertebrate biology.

The Regeneration Process

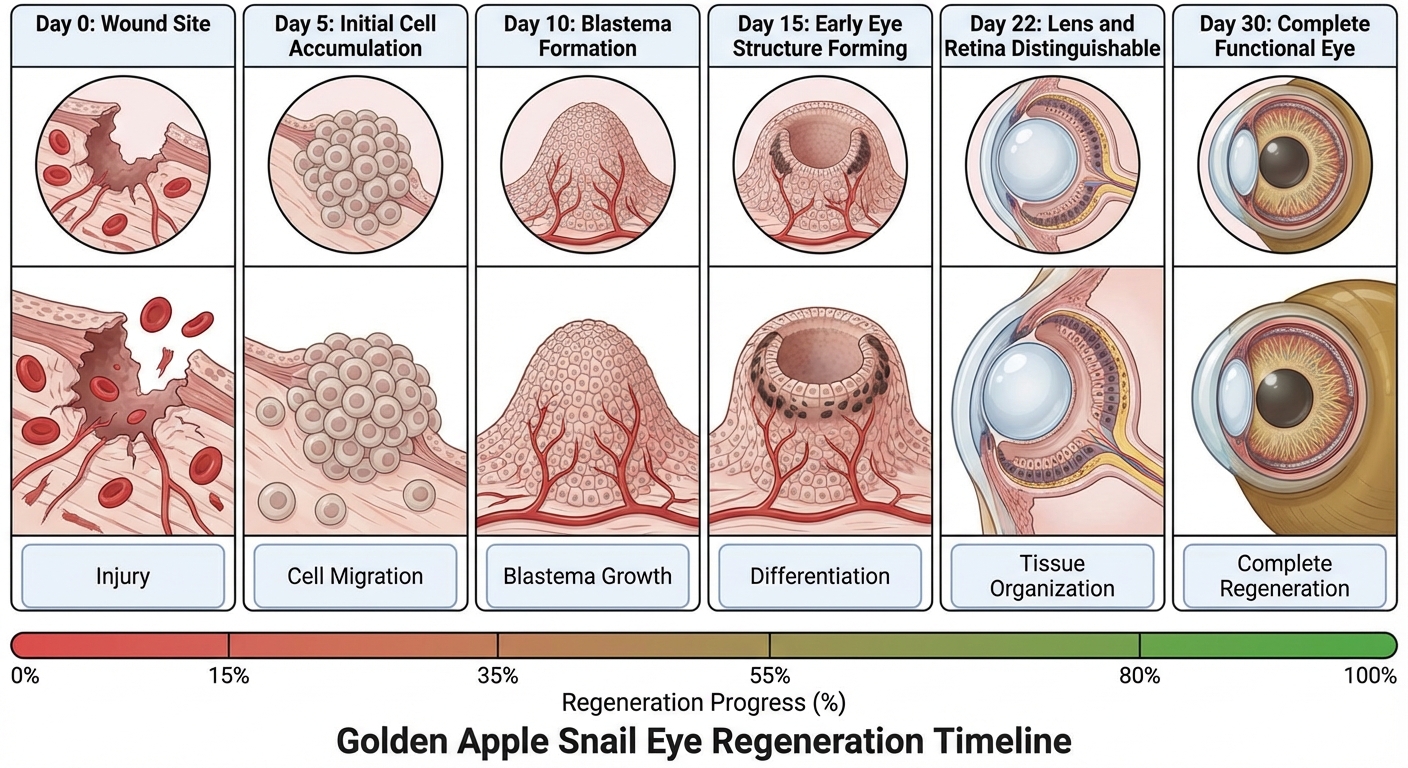

When a golden apple snail loses an eye, typically to a predator that manages only a glancing blow, the healing process begins immediately. First, the wound closes. Then, over the following weeks, cells at the wound site begin to dedifferentiate, reverting from their specialized states to a more flexible, embryonic-like condition. These cells then redifferentiate into the various cell types needed for a functional eye.

The process recapitulates much of what happens during embryonic development, but in an adult animal. The regenerating tissue forms a structure called a blastema, similar to what appears when salamanders regrow limbs. The blastema contains a population of cells capable of becoming any of the cell types needed for the regenerating organ. As the blastema grows, spatial signals direct different regions to develop into different structures: lens here, retina there, optic nerve connecting everything to the brain.

Within about 30 days, the new eye is complete. Tests show that the snails can respond to visual stimuli normally, tracking objects and reacting to changes in light. The regenerated eye isn’t perfect in every case, but it’s functional enough for the snail’s purposes. Given that the alternative is permanent blindness, even imperfect regeneration represents a remarkable biological achievement.

The Genetic Key

Researchers recently identified a key gene involved in golden apple snail eye regeneration. The gene, which has counterparts in many other species including humans, appears to orchestrate the regenerative process by controlling when and where different cell types develop. When the gene is active, regeneration proceeds normally. When it’s suppressed, regeneration stalls.

This finding suggests that the genetic toolkit for regeneration may be broadly conserved across animal lineages. Humans have versions of the same genes that enable snail eye regeneration. In us, those genes are active during embryonic development but largely shut down afterward. The difference between regenerating and non-regenerating species may not be whether they have the necessary genes but whether those genes can be reactivated in adult tissues.

This is exciting for regenerative medicine. If humans retain the genetic capacity for regeneration but simply don’t activate it, future therapies might find ways to switch those genes back on. The goal wouldn’t be to make humans regenerate like snails, which would require far more than just gene activation. But understanding the genetic logic of regeneration could reveal targets for intervention, ways to coax human tissues into repair processes they wouldn’t normally undertake.

Regeneration Across Species

Golden apple snails aren’t the only remarkable regenerators. Planarian flatworms can regrow entire bodies from tiny fragments. Salamanders regrow limbs. Some sea creatures regenerate their entire bodies from what seem like insufficient starting materials. But regeneration of complex sensory organs in organisms with sophisticated vision is relatively rare and particularly relevant to human medicine.

The eyes of most regenerating species are simpler than camera eyes. Planarians have light-sensitive spots that can regenerate but can’t form images. The golden apple snail bridges a gap, demonstrating that complex, image-forming eyes can be rebuilt. This suggests that eye regeneration isn’t fundamentally impossible for sophisticated visual systems; it’s just that most sophisticated species have lost or suppressed the ability.

Evolution doesn’t optimize for every possible advantage. If an organism can survive and reproduce without regenerating lost body parts, selection pressure won’t necessarily maintain regenerative capacity. Regeneration is metabolically expensive and may carry risks, like enabling cancerous growth. Many animals, including humans, may have evolved away from regeneration for reasons that made sense in our evolutionary history but frustrate us now when we face injuries our bodies can’t repair.

The Bigger Picture

The golden apple snail is an unlikely medical research model. It’s an invasive pest in many parts of Asia, damaging rice crops and disrupting ecosystems. Nobody would have chosen it for study based on its agricultural or ecological significance. Yet it demonstrates a biological capability that most organisms lack, and understanding that capability could eventually benefit human medicine.

Biology is full of such surprises. The solutions evolution has found to various problems are distributed across the tree of life in patterns that don’t always match our expectations. A freshwater snail might hold keys to understanding eye regeneration. A jellyfish might illuminate mechanisms of immortality. A tardigrade might reveal secrets of survival under extreme conditions. The diversity of life is also a diversity of biological solutions, waiting to be discovered and potentially applied.

The golden apple snail won’t give us the ability to regrow human eyes anytime soon. The path from understanding a snail gene to developing human therapies is long and uncertain. But every piece of knowledge about how regeneration works adds to our understanding of what’s biologically possible. The snail that regrows its eyes reminds us that some of what we consider impossible is simply unexplored.

Sources: Molluscan biology research on golden apple snail eye regeneration, genetic analysis of regeneration-associated genes, comparative studies of regenerative capacity across species, developmental biology of camera-type eyes.