In a rock shelter in central Spain, archaeologists found a small stone covered in what appeared to be red ochre smudges. The marks weren’t random. When researchers looked closer, they saw something unmistakable: the whorl of a fingerprint, pressed deliberately into the pigment 43,000 years ago. And the finger that made it wasn’t human. It was Neanderthal.

The discovery, announced in late 2025 from the site of Cueva de Ardales, has reignited one of archaeology’s most contested debates: were Neanderthals capable of symbolic thought? The stone, researchers argue, represents “one of the oldest known abstractions of a human face in the prehistoric record.” If they’re right, we may need to reconsider everything we thought we knew about creativity and what makes us unique.

The Find at Ardales

Cueva de Ardales is a limestone cave system in the Málaga province of southern Spain, known to researchers for decades for its wealth of prehistoric remains. The cave contains paintings, engravings, and artifacts spanning tens of thousands of years. But the small stone found in a deep chamber, dated to approximately 43,000 years before present, stands apart.

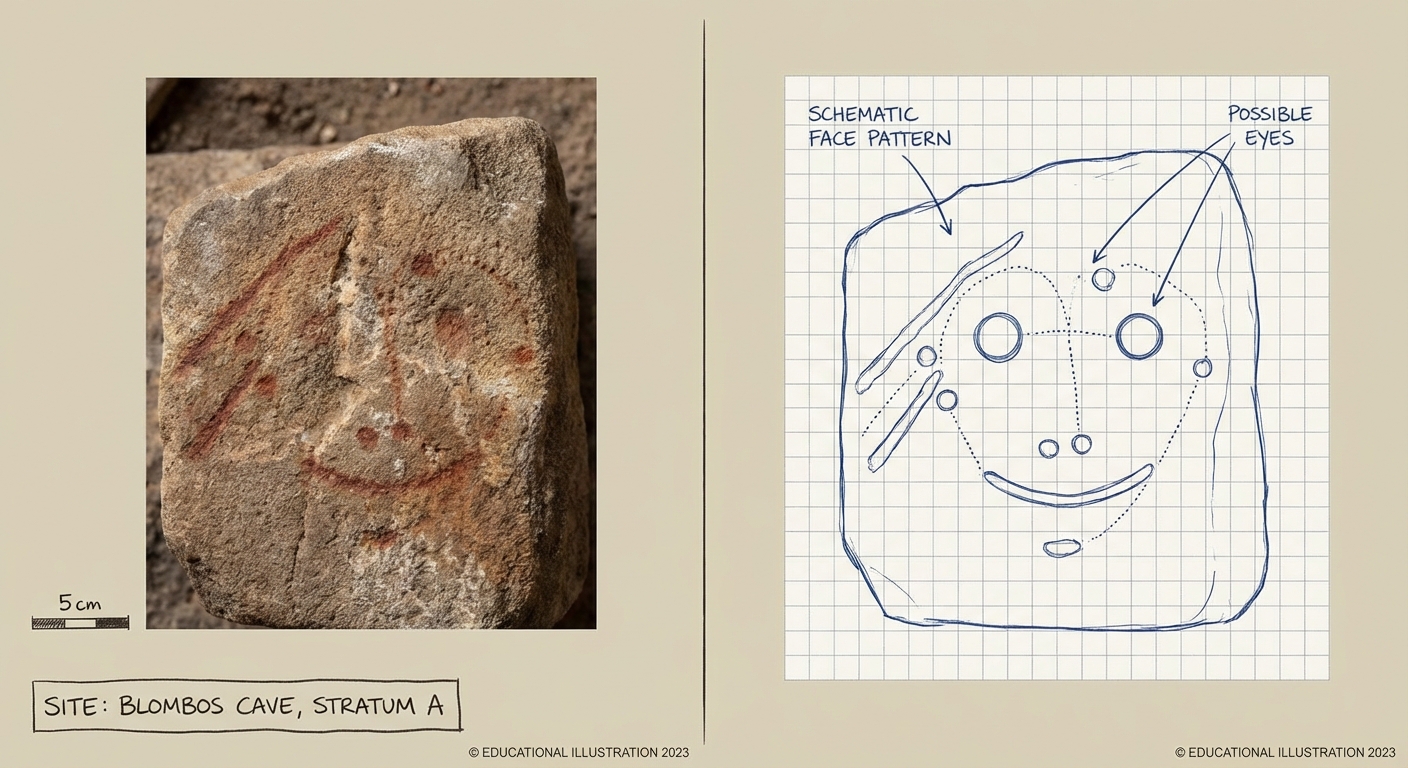

The object is about the size of a fist, irregular in shape, and covered in red ochre, an iron-rich pigment that prehistoric peoples across the world used for everything from body decoration to ritual purposes. What caught researchers’ attention was the pattern of application. The ochre wasn’t simply smeared on. It was applied in discrete marks, including what appears to be a deliberate fingerprint impression.

Using high-resolution imaging and 3D scanning, the research team mapped the marks in detail. They found that the fingerprint was made with purposeful pressure, not accidental contact. The ridges and whorls are clearly visible, preserved in the dried pigment for over 40 millennia. More striking, the team argues that the arrangement of marks may represent a schematic face, with the fingerprint positioned where an eye might be.

The Neanderthal Question

For much of the twentieth century, Neanderthals were portrayed as brutish, dim-witted cousins of modern humans, evolutionary dead ends who lacked the cognitive sophistication for art, language, or symbolic thinking. This view has eroded steadily over the past few decades, but the question of Neanderthal creativity remains controversial.

The evidence for Neanderthal symbolic behavior has accumulated piece by piece. They buried their dead, sometimes with grave goods. They collected eagle talons, possibly for personal ornamentation. They made jewelry from animal teeth and shells. They used ochre, though whether for practical purposes like hide preservation or symbolic purposes like body painting has been debated.

What has been largely absent is clear evidence of representational art. The cave paintings of Lascaux, Altamira, and Chauvet, those stunning depictions of animals and abstract symbols, are all attributed to Homo sapiens. If Neanderthals created art, it hasn’t been definitively identified until now.

The Ardales fingerprint challenges this gap. Dating techniques place it firmly in the period before modern humans arrived in Iberia. The site’s stratigraphy and associated artifacts support a Neanderthal presence. If the interpretation is correct, this small stone represents not just Neanderthal mark-making but intentional symbolic communication: art.

What Makes Something Art?

The question sounds philosophical, but for archaeologists studying prehistoric cognition, it’s intensely practical. What evidence would prove that a mark was made with symbolic intent rather than being accidental or purely functional?

Researchers look for several indicators. Deliberate application suggests intention, distinguishing marks made purposefully from incidental smudges. Patterning indicates planning and design. Use of pigment with no obvious practical function implies symbolic purpose. And representational content, marks that seem to depict something, points toward the capacity for abstraction.

The Ardales stone, its discoverers argue, meets these criteria. The fingerprint was pressed with evident purpose. The surrounding marks show organization rather than randomness. Ochre has no known practical use on a stone of this size. And the arrangement, if you’re willing to see it, resembles a face.

Not everyone is convinced. Critics note that pareidolia, the tendency to see faces in random patterns, is a powerful human bias. We see faces in clouds, toast, and electrical outlets. Could we be projecting meaning onto marks that meant nothing to their maker?

The debate is ultimately about the boundary of inference. At what point does evidence become compelling enough to attribute human-like cognition to another species? The answer depends partly on how much we’re willing to believe Neanderthals were like us.

A Longer History of Creativity

If Neanderthals did create symbolic art, they weren’t alone in their epoch. The archaeological record increasingly suggests that multiple hominin species engaged in behaviors once thought uniquely human.

The earliest known engravings, geometric patterns carved into shells, date to around 500,000 years ago and are attributed to Homo erectus in Java. Ochre use goes back at least 250,000 years across Africa and Europe. By the time Neanderthals were pressing fingerprints into pigmented stones, symbolic behavior may have had a half-million-year history in our lineage.

This longer view changes how we understand human uniqueness. Rather than a sudden cognitive revolution that made Homo sapiens special, the capacity for symbolism may have evolved gradually across multiple species. Our ancestors didn’t invent creativity from nothing; they inherited predispositions built over hundreds of thousands of years.

The Neanderthal fingerprint, if it is art, suggests this capacity was present in our closest relatives. We shared a common ancestor with Neanderthals around 600,000 years ago. If both species developed symbolic expression, the roots of that ability must lie deep in our shared past.

What the Fingerprint Tells Us

Beyond the debate over whether this object constitutes art, the fingerprint itself carries meaning. It’s a trace of an individual, a specific Neanderthal who lived and breathed and pressed their finger into red pigment on a particular day tens of thousands of years ago.

The ridges of a fingerprint are formed in the womb and remain unchanged throughout life. They’re as individual as faces, unique identifiers carried on every hand. When that Neanderthal made this mark, they left something personal, something that could never be duplicated by any other being who ever lived.

Whether this was intentional self-expression or not, it’s hard not to feel the poignancy. Here is evidence of a person, an individual from a species that no longer exists, reaching across an unimaginable span of time. The fingerprint may or may not be art. It is certainly a connection.

The Bigger Picture

The Ardales fingerprint won’t settle the debate over Neanderthal cognition. No single artifact can. But it adds to a growing body of evidence that our extinct relatives were more sophisticated than we once believed, that the line between “us” and “them” may be blurrier than our origin stories suggest.

This matters for how we understand ourselves. If creativity, symbolism, and art are not uniquely human inventions but shared capacities inherited from ancient ancestors, then what we call human nature has deeper roots than we imagined. We are not a sudden miracle of evolution but the latest expression of tendencies millions of years in the making.

The fingerprint also reminds us how much we’ll never know. For every artifact that survives, countless others have crumbled to dust. For every behavior that leaves archaeological traces, others left nothing. The Neanderthals lived for hundreds of thousands of years across a vast geographic range. This one stone can only hint at the richness of their inner lives.

Perhaps the most important thing the fingerprint tells us is to stay humble. The story of human evolution is not finished. New discoveries continue to complicate and enrich our understanding. What we believe today about Neanderthals, about our ancestors, about ourselves, will look different in another fifty years. The fingerprint endures; our interpretations of it are works in progress.