The Romans built roads that still carry traffic, aqueducts that still channel water, and legal principles that still govern nations. Yet the same industrial ambition that made Rome great may have slowly poisoned its greatest resource: the minds of its citizens. New research published in early 2026 confirms what historians have long suspected but couldn’t prove. The Romans didn’t just use lead in their pipes, cosmetics, and wine sweeteners. They breathed it, in concentrations high enough to impair brain development across generations.

The findings come from an unlikely source: ice cores drilled from Greenland’s glaciers, preserving 2,000 years of atmospheric history in frozen layers. By analyzing trace metals trapped in ancient ice, researchers have reconstructed a startling timeline. Around 15 BCE, lead levels in the atmosphere spiked dramatically and remained elevated for roughly two centuries, coinciding precisely with Rome’s peak power and the beginning of its long decline. The lead didn’t come from plumbing. It came from the air itself, released by the massive smelting operations that fueled Rome’s currency-based economy.

This discovery transforms our understanding of ancient Rome from a cautionary tale about lead pipes into something far more troubling: a civilization that industrialized itself into cognitive decline, a process so gradual that no one at the time could have recognized it was happening.

The Scale of Roman Metallurgy

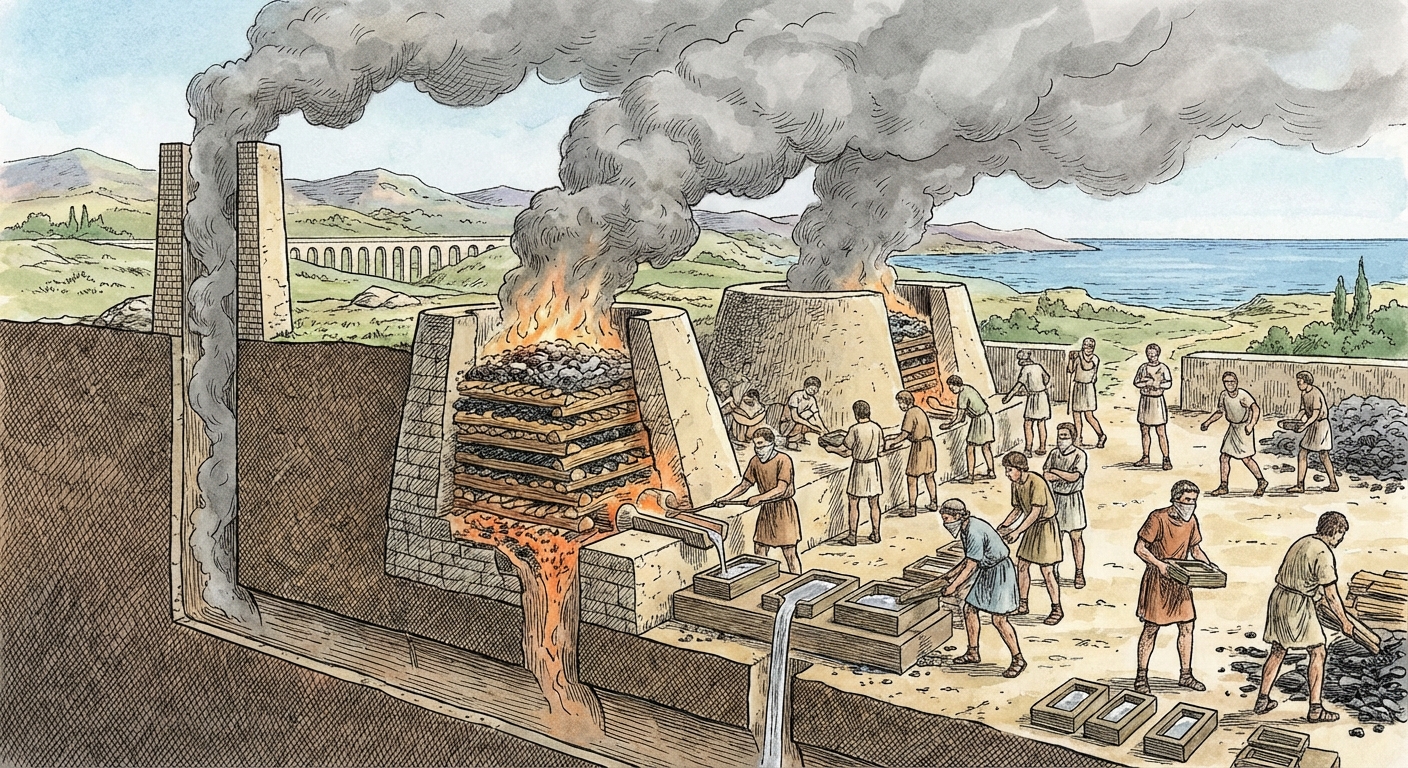

When we imagine ancient industry, we typically picture small workshops and artisan craftsmen. Roman metallurgy operated on a different scale entirely. To maintain its currency system and satisfy its appetite for lead products, Rome smelted an estimated 80,000 tons of lead annually at its peak. This wasn’t scattered across countless small operations. Massive smelting complexes concentrated production in regions like southern Spain, where the mines of Rio Tinto operated continuously for centuries.

The process was straightforward but dirty. Lead ore was heated in open furnaces, releasing clouds of metal-laden smoke that rose into the atmosphere. Some of it settled locally, contaminating soil and water for miles around mining sites. But much of it traveled farther, caught by prevailing winds and carried across the Mediterranean, eventually depositing trace amounts as far away as Greenland. The ice cores record this pollution with remarkable precision, showing lead concentrations that rose steadily during the Roman Republic, peaked during the early Empire, and crashed during periods of plague and political instability.

The implications for public health were severe. Lead is a cumulative neurotoxin, meaning it builds up in the body over time and doesn’t easily flush out. Even low levels of exposure impair cognitive function, particularly in developing brains. Modern studies have linked childhood lead exposure to reduced IQ, increased aggression, and poor impulse control. The Romans weren’t just exposed to low levels. They were bathed in it, drinking it in their wine, absorbing it through their skin from cosmetics, and breathing it with every breath.

Previous research had focused primarily on dietary and water-based exposure, calculating that wealthy Romans who drank wine sweetened with lead-based sapa may have consumed enough to cause acute poisoning. But the new atmospheric data suggests the problem was far more democratic. Rich and poor alike breathed the same air, meaning lead exposure wasn’t limited to those who could afford lead-glazed pottery or sweetened wine. The entire population was affected.

What Lead Does to the Brain

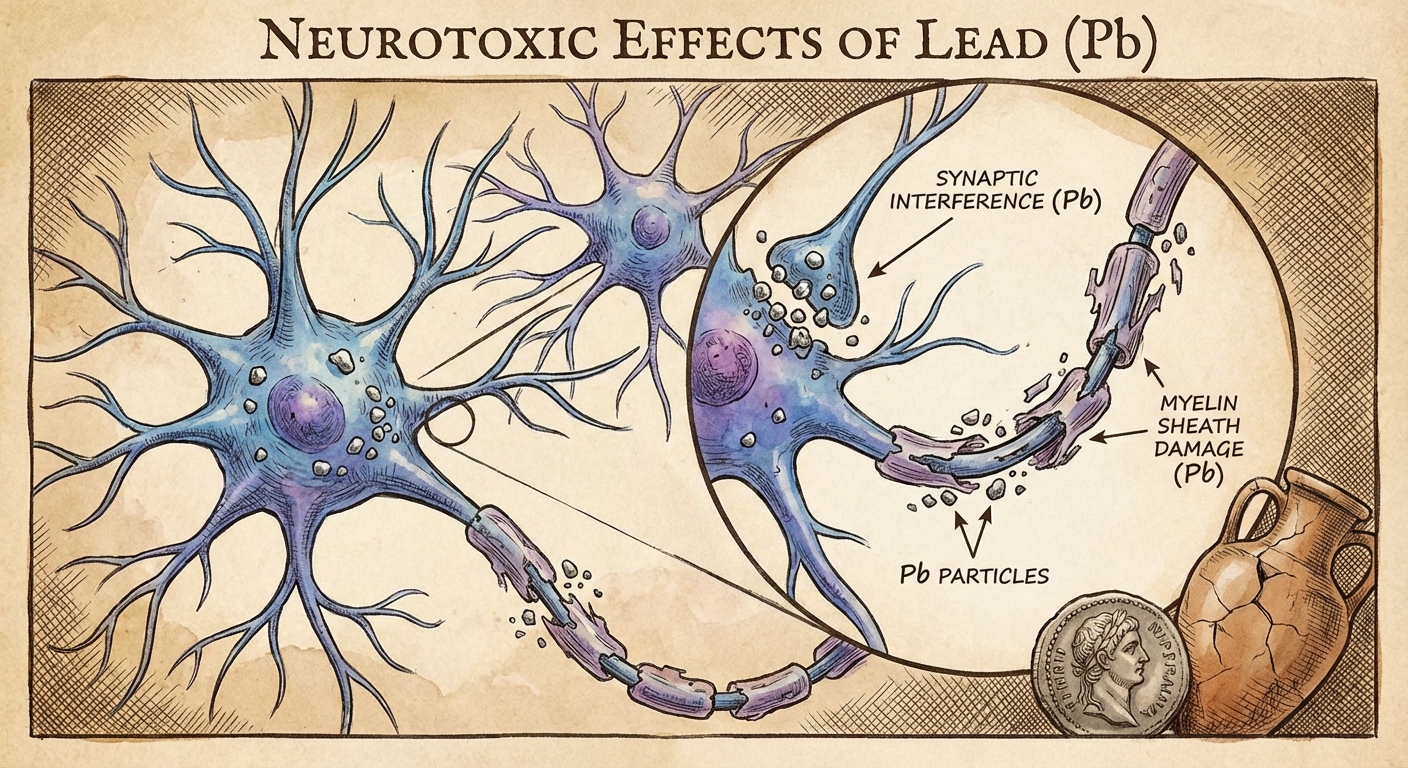

Understanding why atmospheric lead matters requires a brief detour into neuroscience. Lead interferes with brain function through multiple mechanisms, none of them subtle. It mimics calcium, allowing it to cross the blood-brain barrier and disrupt neural signaling. It damages the myelin sheath that insulates nerve fibers, slowing communication between brain regions. It triggers oxidative stress, killing neurons outright. And it’s particularly devastating during development, when the brain is rapidly forming the connections that will govern thought and behavior for a lifetime.

The effects of chronic low-level exposure are insidious precisely because they’re invisible. Someone with elevated blood lead levels doesn’t feel poisoned. They simply think a little less clearly, react a little more impulsively, learn a little more slowly. Multiply these subtle impairments across an entire population, and the cumulative effect becomes significant. Studies of modern populations have found that even modest increases in average blood lead levels correlate with measurable declines in average IQ and increases in crime rates.

The Romans, of course, had no concept of neurotoxins or blood lead levels. They noticed that workers in lead mines and smelting operations tended to sicken and die, but they attributed this to the mines themselves rather than to the metal being extracted. The Greek physician Nicander described lead poisoning symptoms as early as the second century BCE, and Roman authors occasionally noted the dangers of lead fumes to workers. But no one connected these industrial hazards to broader public health, partly because the symptoms of chronic low-level exposure are so different from acute poisoning.

What makes the new research particularly compelling is the timeline it reveals. Lead levels in the ice cores track remarkably well with Roman economic output, rising during periods of prosperity and falling during crises. The correlation isn’t perfect, since other factors influenced atmospheric lead, but the overall pattern is clear. When Rome was rich and powerful, it was also pumping unprecedented amounts of lead into the air its citizens breathed.

The Emperor Problem

One of the most intriguing aspects of the lead hypothesis concerns Roman leadership. The empire’s later history is marked by a parade of emperors whose behavior ranged from merely incompetent to spectacularly unhinged. Caligula allegedly planned to make his horse a consul. Nero fiddled while Rome burned, then blamed Christians for the fire. Commodus abandoned governance to fight as a gladiator. These stories may be exaggerated by hostile historians, but the pattern of erratic imperial behavior is too consistent to dismiss entirely.

Lead poisoning could help explain this pattern, though we should be cautious about oversimplifying. The emperors and their families had more exposure to lead than ordinary citizens through their diet, since wealthy Romans consumed more wine, more lead-sweetened sauces, and more food prepared in lead-glazed cookware. They also lived in homes decorated with lead-based paints and drank water that had traveled through lead pipes. By some estimates, the Roman elite may have consumed hundreds of times more lead than the typical modern person.

The symptoms of chronic lead poisoning align disturbingly well with the behavioral descriptions that survive from this period: irritability, paranoia, poor judgment, and sudden mood swings. Several emperors also displayed what appear to be neurological symptoms, including tremors, seizures, and cognitive decline. Claudius’s contemporaries mocked his physical tics and stumbling speech, characteristics that modern physicians have suggested might indicate neurological damage. Of course, other explanations exist for any individual case, but the cumulative pattern is suggestive.

Perhaps more important than individual emperors is what lead exposure might have meant for the broader governing class. Roman administration depended on a relatively small elite who managed the empire’s vast territories. If this class was systematically impaired by lead exposure, even modestly, the effects on governance would compound over time. Decisions would be slightly worse, reactions to crises slightly slower, long-term planning slightly less coherent. No single choice would doom the empire, but the accumulated weight of suboptimal decisions across generations might erode the institutional resilience that had allowed Rome to survive earlier challenges.

The Fall That Wasn’t Quite a Fall

Historians have proposed dozens of explanations for Rome’s decline and eventual fall: barbarian invasions, economic collapse, military overextension, religious transformation, climate change, and plague, among others. The lead hypothesis doesn’t replace any of these explanations. Instead, it adds another layer to an already complex picture, suggesting that the empire may have been fighting its external challenges with a cognitively impaired population and leadership class.

The ice core data also reveals something unexpected about the timing of Rome’s decline. Lead levels in the atmosphere dropped significantly during the crisis of the third century, when plague, civil war, and economic collapse disrupted mining and smelting operations. They rose again during the fourth century recovery, then fell permanently with the western empire’s final collapse. This pattern suggests an ironic possibility: the periods of greatest Roman crisis may have also been periods of relative cognitive recovery, as reduced industrial activity cleared the air of lead pollution.

This doesn’t mean that Rome fell because of lead poisoning. The western empire’s collapse in the fifth century had immediate causes, primarily the migration and invasion of Germanic peoples, that lead exposure didn’t create. But lead may have made the empire less capable of responding to these challenges than it might otherwise have been. A society where average cognitive function was slightly depressed, where elite decision-making was slightly impaired, and where impulse control was slightly compromised would have had fewer resources to draw on when facing existential threats.

The hypothesis also raises uncomfortable questions about other industrial civilizations, including our own. The Romans didn’t know they were poisoning themselves. They saw their smelting operations as markers of progress and prosperity, the industrial foundation of a great civilization. The environmental costs were invisible to them, dispersed across vast distances and manifesting as subtle impairments rather than obvious illness. We now understand the dangers of lead and have largely eliminated it from our immediate environment, but we face our own invisible pollutants whose effects may not become clear for generations.

The Bigger Picture

The story of Roman lead is ultimately a story about unintended consequences and the limits of what any civilization can see about itself. The Romans were sophisticated engineers who built infrastructure that lasted millennia. They developed complex legal systems and administrative structures. They created art and literature that still moves us. Yet they couldn’t perceive that their industrial success was slowly compromising their collective cognitive capacity. The poison was too gradual, too diffuse, and too intertwined with the markers of prosperity to recognize as a threat.

This blindness wasn’t stupidity. It was a structural limitation that affects all complex societies. The costs of certain choices are dispersed across time and space in ways that make them effectively invisible to decision-makers focused on immediate benefits. Roman mine owners saw profits and production quotas. Roman consumers saw the goods they wanted at prices they could afford. Roman emperors saw the tax revenues that funded their armies and building projects. What no one could see was the accumulated neurological damage building up across generations, invisible until we learned to read its signature in Greenland ice.

The new research on Roman lead exposure joins a growing body of work connecting environmental factors to historical outcomes. Climate shifts have been linked to the rise and fall of civilizations across the globe. Volcanic eruptions have been connected to famines and political upheavals. Disease outbreaks have shaped the fate of empires. Lead poisoning adds another variable to these analyses, reminding us that the relationship between human societies and their environments is more intimate and consequential than we often recognize.

For those interested in how accurate timekeeping shaped civilization, the Roman lead story offers an interesting contrast. Both involve technologies that transformed society in ways their creators couldn’t fully anticipate. The difference is that clocks enhanced human capability while lead smelting silently eroded it. Similarly, just as coffee’s arrival in Europe may have sharpened Enlightenment minds by replacing alcoholic beverages with a stimulant, Roman lead may have dulled minds across the ancient world by contaminating the very air people breathed.

What makes this history relevant isn’t the opportunity to feel superior to ancient Romans who didn’t understand neurotoxins. It’s the reminder that every civilization has blind spots, things it can’t see because they’re too diffuse, too gradual, or too intertwined with what that civilization considers progress. Identifying our own blind spots is one of the hardest challenges any society faces. The Romans couldn’t know that their prosperity was partly built on a foundation of cognitive self-harm. The question for us is what equivalent costs we might be accumulating, invisible until some future researcher learns to read their signature in the record we’re leaving behind.