The Roman god Janus looked both backward and forward, and the month named for him has earned its reputation as a time of beginnings, endings, and transformations. January has witnessed the founding of nations, the deaths of kings, scientific breakthroughs that rewired human understanding, and quiet moments that only later revealed their world-changing significance. To trace these events is to see history not as a smooth progression but as a series of pivots, moments when the future suddenly looked different from what anyone expected.

What makes January particularly rich for historical exploration is its position as a threshold month. Across cultures and centuries, people have used this time to make resolutions, inaugurate leaders, and launch ambitious enterprises. The cold of winter, at least in the Northern Hemisphere where most recorded history unfolded, concentrates people indoors, leading to political intrigues, literary creations, and the kind of thinking that changes everything. Let us trace some of the most fascinating events that January has delivered across the centuries.

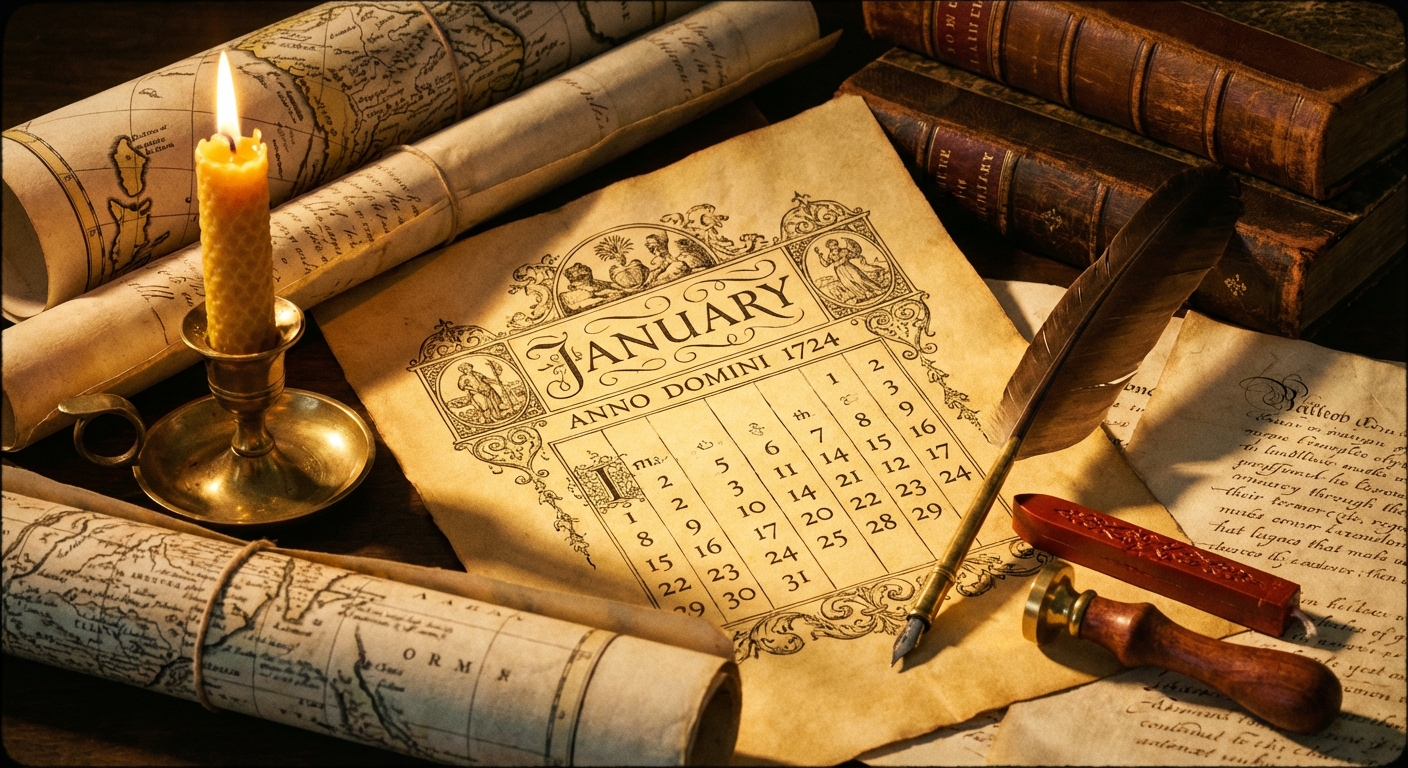

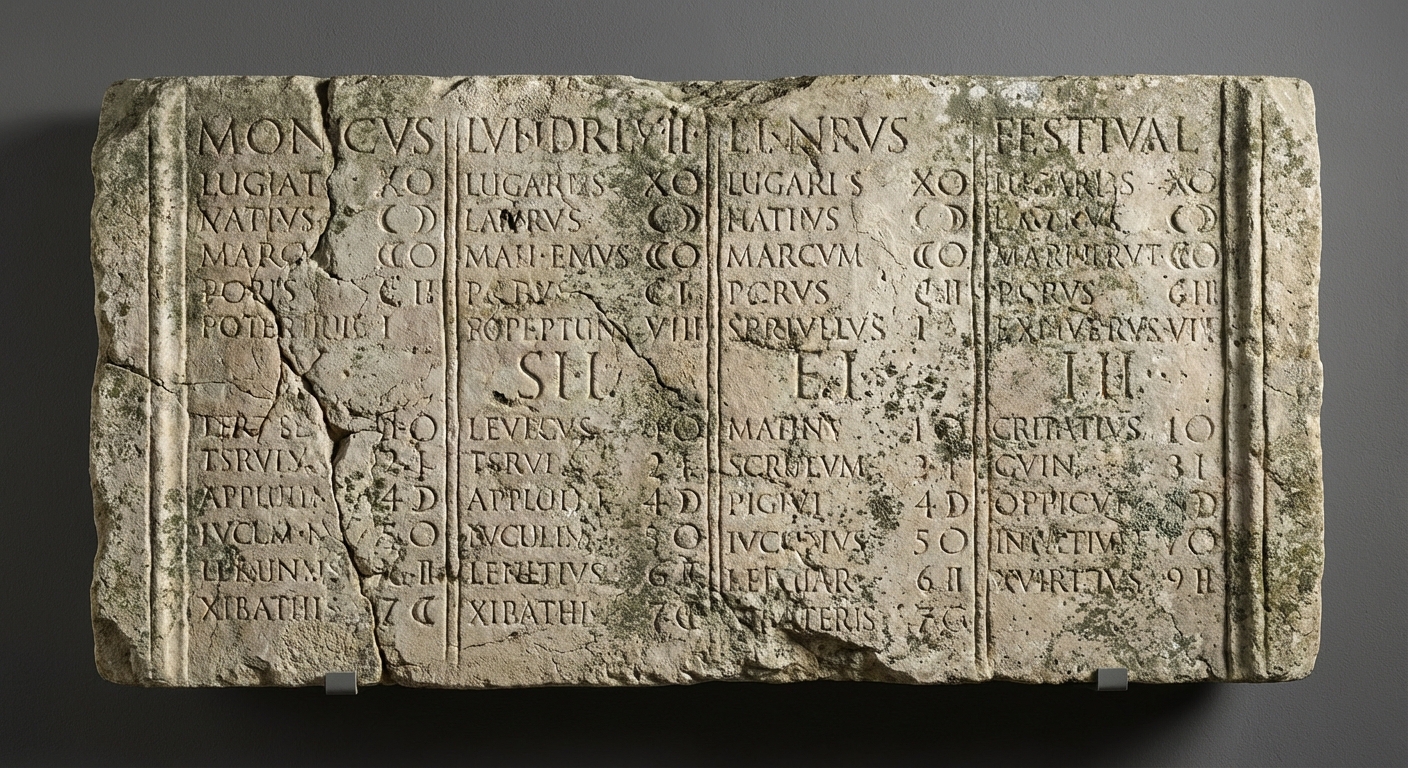

When Julius Caesar Changed Time Itself

On January 1, 45 BCE, something unprecedented occurred: the Julian calendar went into effect, and for the first time in centuries, Roman dates actually corresponded to the seasons. This might sound like a minor administrative adjustment, but how humans measure time shapes everything about civilization, from agriculture to religious observance to the coordination of empires.

Before Caesar’s reform, the Roman calendar had become a chaotic mess. The pontiffs charged with adding extra days to keep the calendar aligned with the solar year had been negligent for decades, sometimes intentionally, to extend political terms or hasten elections. By 46 BCE, the calendar had drifted so far from astronomical reality that the harvest festival fell in spring and the month of March arrived during what should have been winter. Caesar, having just consolidated power after defeating Pompey in civil war, recognized that reforming the calendar was both practically necessary and symbolically powerful.

Caesar consulted the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, who recommended a solar calendar of 365 days with a leap day every four years. To realign the calendar with the seasons, 46 BCE had to last 445 days, earning it the nickname “the year of confusion.” When January 1, 45 BCE finally arrived, it marked the start of a timekeeping system that would endure, with one minor correction in 1582, until the present day. Every time you write a date, you are using a system Julius Caesar imposed on a confused republic two millennia ago.

The calendar reform also established January as the first month of the year, a status it had not always held. Earlier Roman calendars began in March, which is why September, October, November, and December bear names suggesting they are the seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth months. By moving the new year to January, Caesar tied it to the start of the consular term, when new leaders took office. The choice was political as much as astronomical, and it stuck.

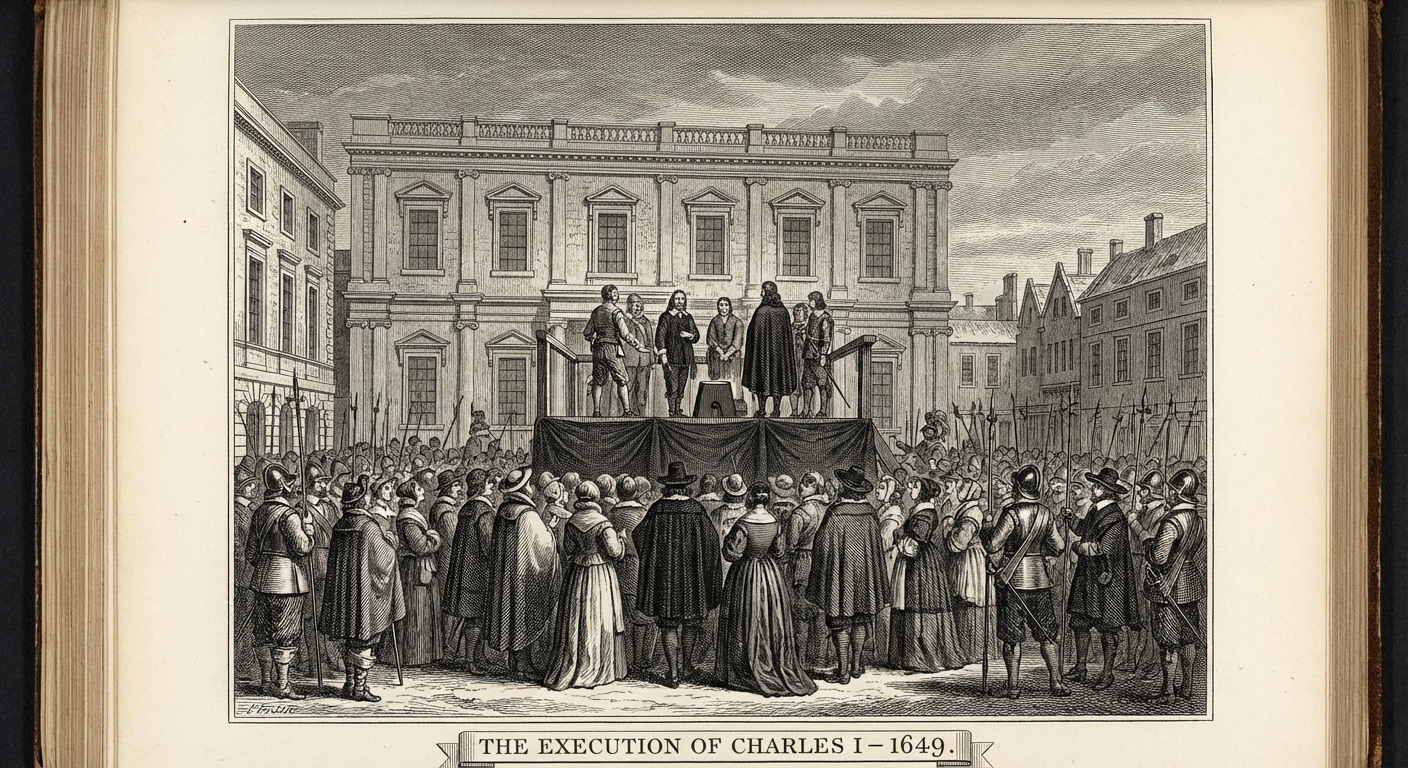

The Execution That Shook Europe

On January 30, 1649, King Charles I of England walked through the Banqueting House in Whitehall, stepped onto a scaffold erected outside one of its windows, and placed his head on the block. The executioner, his identity concealed beneath a mask and false beard, severed the king’s head with a single blow. A groan rose from the crowd, some of whom rushed forward to dip handkerchiefs in the royal blood, either as relics or souvenirs.

The execution of Charles I was not merely the death of a man but the death of an idea that had structured European politics for centuries: that kings ruled by divine right and were accountable only to God. The English Civil War that preceded his execution was fought over precisely this question. Charles believed that his authority came from heaven, that Parliament existed only at his pleasure, and that he could rule without it if he chose. Parliament disagreed.

The trial itself was legally dubious by any standard. No precedent existed for trying a king, and many questioned whether any court could claim jurisdiction over God’s anointed. Charles refused to recognize the legitimacy of the proceedings, never entering a plea and addressing the court only to question its authority. He was convicted of treason against the people of England, a concept that would have seemed absurd to most Europeans of the era, who understood treason as a crime against the monarch rather than by the monarch.

The aftershocks lasted for decades. Oliver Cromwell established a republican Commonwealth that lasted until 1660, when Charles II was invited back to restore the monarchy. But the restored monarchy operated under new constraints, and the principle that kings could be held accountable had entered European political consciousness permanently. When the French revolutionaries executed Louis XVI in 1793, they explicitly invoked the English precedent. The scaffold outside Whitehall cast a long shadow.

The Discovery That Rewrote Human Origins

January 9, 1923, was unremarkable in most of the world. But in a small laboratory at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, a young anatomist named Raymond Dart was examining a peculiar fossil that had been brought to him from a limestone quarry near the village of Taung. What he saw would eventually transform our understanding of human origins.

The fossil was a small skull, clearly of a primate, but with features that did not match any known ape. The foramen magnum, the hole through which the spinal cord connects to the brain, was positioned underneath the skull rather than toward the back. This placement indicated that the creature had walked upright. The teeth showed a mix of human and ape characteristics. Dart recognized that he was looking at something new: an ancient relative of humans that had lived in Africa millions of years ago.

Dart named his discovery Australopithecus africanus, the “southern ape from Africa,” and published his findings in 1925. The scientific establishment was skeptical, even hostile. The prevailing view held that human ancestors would be found in Asia, not Africa, and that our large brains had evolved before our upright posture. Dart’s fossil suggested the opposite: bipedalism came first, and Africa was the cradle of humanity.

It took decades for Dart to be vindicated. Additional australopithecine fossils discovered across Africa throughout the twentieth century confirmed that our earliest ancestors did indeed walk upright in Africa millions of years before the genus Homo evolved. The Taung Child, as Dart’s specimen came to be known, remains one of the most important fossils ever discovered, a key that unlocked the deep history of human evolution. January brought that key into human hands.

Revolution on Ice

The Russian Revolution is usually associated with October 1917, when Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace and seized power. But the seeds of that revolution were planted the previous winter, in January 1917, when strikes erupted across Petrograd despite the bitter cold. Understanding what happened in January helps explain why the Romanov dynasty, which had ruled Russia for three centuries, collapsed so suddenly.

Russia in January 1917 was a nation exhausted by war and starving for bread. World War I had killed millions of Russian soldiers, and the infrastructure for feeding the cities had broken down. The temperature in Petrograd dropped to minus 35 degrees Celsius, and fuel was scarce. Workers could neither eat nor stay warm, and their patience had evaporated. On January 22, the anniversary of Bloody Sunday, when tsarist troops had massacred peaceful protesters in 1905, 150,000 workers walked out of their factories and into the frozen streets.

The January strikes did not immediately topple the government, but they revealed the depth of popular discontent and the weakness of tsarist authority. Police and Cossack units proved unreliable, sometimes refusing to fire on protesters or joining them outright. When larger protests erupted in February (March by the Western calendar that Russia had not yet adopted), the army’s refusal to crush them sealed the regime’s fate. Tsar Nicholas II abdicated on March 15, ending a dynasty that had ruled since 1613.

The Bolsheviks who eventually took power exploited the chaos that followed, but the revolution’s momentum built during those cold January days when ordinary workers decided they had nothing left to lose. Revolutions do not happen because ideas spread; they happen because material conditions become intolerable. January 1917 demonstrated this truth with particular clarity.

The Birth of a Superpower

On January 1, 1959, a bearded guerrilla commander named Fidel Castro rode into Havana at the head of a rebel army, having overthrown the dictator Fulgencio Batista. The Cuban Revolution would transform not only Cuba but the entire geopolitical landscape of the Cold War, bringing the world closer to nuclear annihilation than at any other moment in history.

Castro’s revolution began as a nationalist movement against a corrupt regime that served American business interests while most Cubans lived in poverty. Batista had seized power in a coup in 1952, canceled elections, and ruled through a combination of military force and American support. The United States, more concerned with stability than democracy, backed Batista because he opposed communism and welcomed American investment. Cuban sugar, nickel, and casinos enriched a small elite while rural Cubans cut sugarcane for wages that barely sustained life.

Castro, a lawyer from a wealthy family, had attempted to spark revolution in 1953 by attacking military barracks. The assault failed, but his courtroom defense, which concluded with the declaration “History will absolve me,” made him a hero to many Cubans. Released from prison, he regrouped in Mexico, recruited followers including the Argentine revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and returned to Cuba in 1956 to wage guerrilla war from the Sierra Maestra mountains.

What began as a nationalist revolution became something else once Castro took power. Facing American hostility and an economic embargo, Castro aligned Cuba with the Soviet Union, accepting military and economic aid in exchange for hosting Soviet missiles. This decision led directly to the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, when the United States and Soviet Union came within hours of nuclear war. The crisis was resolved through negotiation, but Cuba remained a Soviet ally for three more decades, a communist state ninety miles from Florida that seemed to refute American claims that its system represented the inevitable future of humanity.

Science in the Cold

January has proven particularly fruitful for scientific discoveries, perhaps because the cold weather concentrates researchers indoors and the new year inspires fresh investigations. Some of the most consequential scientific announcements in history came during this month, reshaping human understanding of nature and our place within it.

On January 7, 1610, Galileo Galilei pointed his newly improved telescope at Jupiter and noticed three small stars near the planet. Over subsequent nights, he observed that these “stars” moved relative to Jupiter, and eventually realized he was seeing moons orbiting a planet other than Earth. This discovery, published later that year in “Sidereus Nuncius” (The Starry Messenger), provided crucial evidence for the Copernican theory that Earth was not the center of the universe. How we understand our place in the cosmos shapes everything else, and Galileo’s January observations began that transformation.

January 1912 brought another paradigm shift when Alfred Wegener presented his theory of continental drift to the German Geological Association. Wegener had noticed that the coastlines of Africa and South America fit together like puzzle pieces and that similar fossils appeared on continents now separated by oceans. He proposed that all continents had once formed a single supercontinent, which he called Pangaea, and had drifted apart over geological time. The establishment ridiculed him because he could not explain what force moved continents. It was not until the 1960s, when plate tectonics provided the mechanism, that Wegener was posthumously vindicated.

January 17, 1773, marked the moment when Captain James Cook and his crew crossed the Antarctic Circle, becoming the first humans known to have done so. Although Cook never sighted the Antarctic continent itself, his voyage proved that the vast southern landmass imagined by ancient geographers did not exist in temperate latitudes. If a continent lay beyond the ice, it would be colder and more inhospitable than anyone had imagined. Cook’s January crossing opened an era of Antarctic exploration that continues today.

The Bigger Picture

Looking across these January events, certain patterns emerge. The month has witnessed fundamental reorderings of power, from Caesar’s calendar reform to Charles I’s execution to Castro’s revolution. It has seen scientific discoveries that challenged established worldviews, from Galileo’s moons to Dart’s australopithecine. And it has marked moments when ordinary people, like the workers of Petrograd, found their patience exhausted and their willingness to accept the existing order depleted.

These events remind us that history does not flow smoothly but lurches from one configuration to another, often at moments no one predicted. Caesar could not have foreseen that his calendar reform would outlast the empire he built. Charles I surely did not expect that his insistence on divine right would cost him his head. Dart could not have imagined that a small fossil from a South African quarry would rewrite human origins. The future arrives through such surprises.

As we pass through another January, we might consider what events of our own time will be remembered centuries hence. The month continues to deliver significant moments: treaties signed, discoveries announced, leaders inaugurated. Somewhere, perhaps, something is happening this January that future historians will regard as a pivot point, a moment when everything changed. We likely will not recognize it when it happens. That is how history works, revealing its significance only in retrospect, when the fog of the present has lifted and the shape of consequences becomes clear. Janus looked both ways, and so must we.