For 4,500 years, the Great Pyramid of Giza has kept its secrets. Generations of explorers, archaeologists, and treasure hunters have probed its passages, mapped its chambers, and speculated about what else might lie hidden within its 2.3 million stone blocks. Now, after nearly a decade of scanning the pyramid with cosmic rays and other advanced technologies, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass has announced that a previously unknown structure inside Khufu’s monument will be revealed to the world in 2026. The discovery, made using muon tomography and other non-invasive imaging techniques, involves a void approximately 30 meters long, hidden above the pyramid’s Grand Gallery where no one expected to find anything at all.

The announcement, made at the 44th Sharjah International Book Fair in late 2025, represents the culmination of years of painstaking work by international research teams. The void was first detected in 2017 by the ScanPyramids project, a collaboration between Egyptian authorities and researchers from France and Japan. At the time, the discovery was greeted with both excitement and caution. Detecting an empty space inside millions of tons of limestone is one thing. Understanding what that space is, whether it’s a burial chamber, a construction artifact, or something else entirely, requires much more information than muon tomography alone can provide.

What makes this moment significant isn’t just the existence of the void, which has been known for years, but the apparent confidence with which researchers are now approaching its interpretation. Additional scanning campaigns, using multiple muon detection techniques positioned at different angles around the pyramid, have produced increasingly detailed images of the structure’s size, shape, and position. The upcoming revelation promises to explain not just what the void is but why it exists, a question that connects to some of the deepest mysteries about how and why the pyramids were built.

How Cosmic Rays See Through Stone

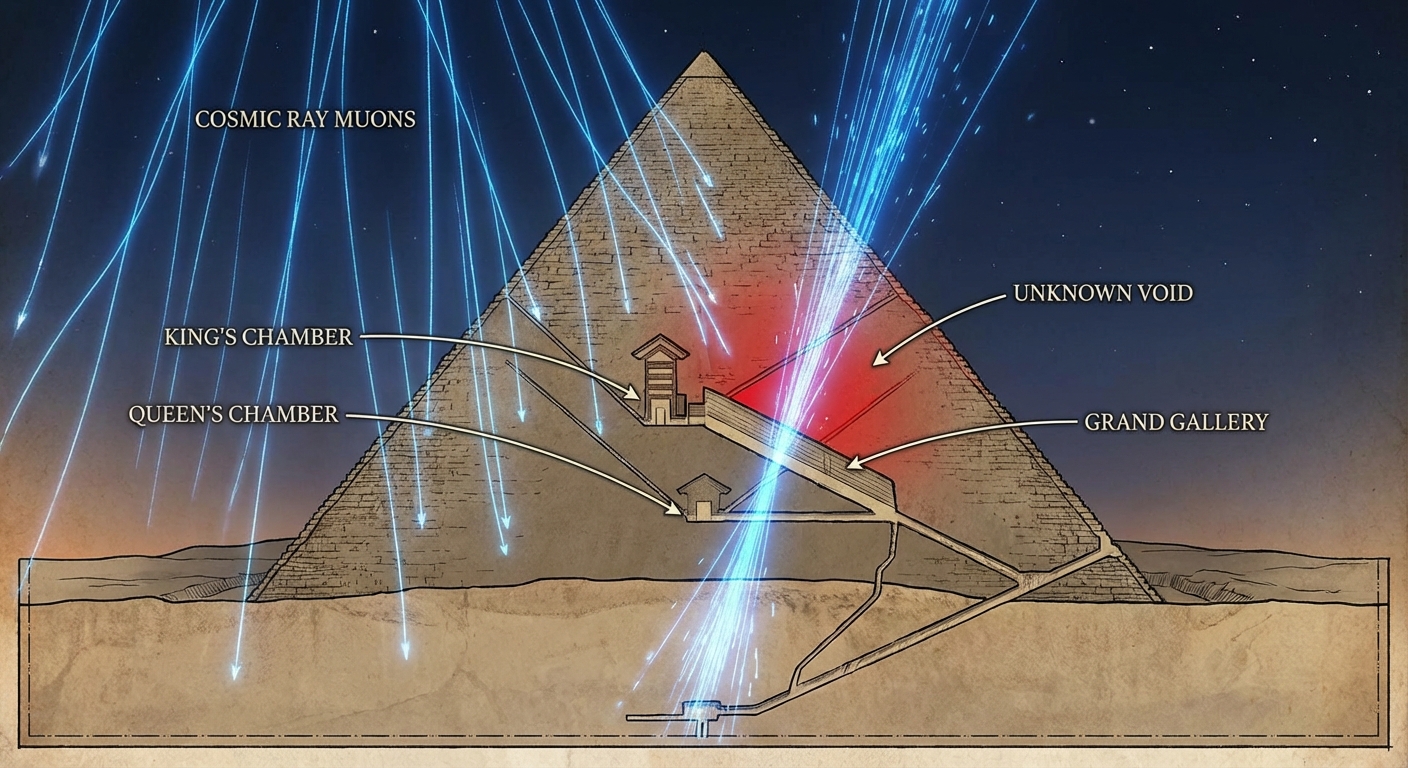

The technology that made this discovery possible sounds like science fiction but relies on entirely natural phenomena. Cosmic rays constantly bombard Earth from space, colliding with atoms in the atmosphere and producing showers of subatomic particles called muons. These muons rain down continuously, passing through matter like tiny bullets. When muons encounter dense material, some are absorbed. When they encounter empty space, they pass through unimpeded. By placing muon detectors inside or around a structure and counting how many muons arrive from different directions, researchers can essentially create a shadow image of what lies between the cosmic ray source and the detector.

For the Great Pyramid, this technique offered something unprecedented: a way to look inside without drilling, digging, or removing a single stone. The ScanPyramids team positioned muon detectors in the Queen’s Chamber, one of the pyramid’s known internal spaces, and recorded muon arrivals over many months. The data revealed an excess of muons coming from a specific direction above the Grand Gallery, indicating a significant void where solid stone was expected. Subsequent scanning campaigns, using different detector technologies and positions, confirmed the finding and refined estimates of the void’s dimensions.

The technique has limitations. Muon tomography can tell you where empty spaces are, but it can’t tell you what’s inside those spaces or why they exist. A burial chamber, a construction ramp, a stress-relief feature, and an architectural decoration would all look similar to muon detectors, appearing simply as areas where fewer muons are absorbed. This is why the discovery, while announced in 2017, has required years of additional investigation before researchers felt confident making claims about what the void actually represents.

The additional scanning campaigns employed multiple approaches. Teams placed detectors outside the pyramid to image it from different angles. They used different types of muon detection technology, including nuclear emulsion films that provide extremely high resolution at the cost of long exposure times. They combined muon data with other imaging techniques and with detailed structural analysis of the pyramid’s known architecture. The synthesis of all this information has apparently produced enough clarity for Hawass to announce an imminent revelation, though the full details remain closely guarded.

The Pyramid’s Known and Unknown Spaces

To understand why the new void matters, you need to understand what was already known about the Great Pyramid’s interior. From the outside, the pyramid appears as a solid mass of stone. Inside, it contains a complex system of passages and chambers whose purposes archaeologists have debated for centuries.

The main known features include the underground chamber cut into the bedrock beneath the pyramid, reached by a descending passage from the entrance. Above this, the ascending passage leads to the Grand Gallery, a spectacular corbelled corridor nearly 47 meters long and 8 meters high that represents one of the architectural wonders of the ancient world. The Grand Gallery opens into the King’s Chamber, where a large granite sarcophagus sits empty, its original contents having vanished long ago. A horizontal passage branches off to the Queen’s Chamber, which despite its name probably never contained a queen’s burial.

Above the King’s Chamber are five stress-relief chambers, small spaces stacked vertically that were apparently designed to distribute the weight of the stone above and prevent the King’s Chamber’s ceiling from collapsing. These were discovered in the 19th century when explorers noticed that the King’s Chamber’s ceiling consisted of granite beams rather than the expected limestone, and subsequent investigation revealed the chambers above. The discovery demonstrated that ancient Egyptian builders understood the structural challenges they faced and devised sophisticated solutions.

The newly detected void sits above the Grand Gallery, in a location where no chamber was expected or documented. Its position and size suggest it’s a significant architectural feature rather than a small anomaly or construction gap. The void runs roughly parallel to the Grand Gallery, creating what researchers have described as a kind of shadow structure hidden within the pyramid’s mass. Whether it served a structural purpose, like the stress-relief chambers above the King’s Chamber, or represents something else entirely remains the central question.

What Could It Be?

Speculation about the void’s purpose has ranged from the mundane to the spectacular. The most conservative interpretation suggests it’s a construction feature, perhaps related to the internal ramps that some researchers believe were used to build the pyramid. In this view, the void would be a remnant of the construction process rather than a deliberate architectural feature, interesting for understanding how the pyramid was built but not containing anything remarkable.

A more exciting possibility is that the void represents an undiscovered chamber, perhaps connected to the pyramid’s original burial function. The King’s Chamber sarcophagus was found empty, and no intact royal burial has ever been discovered within the Great Pyramid. Some researchers have long suspected that the known chambers might be decoys or diversions, with the true burial located elsewhere within the structure. The void’s existence doesn’t prove this theory, but it provides a potential location for such a hidden burial.

There’s also a middle ground: the void might be a deliberate architectural feature that served some purpose in the pyramid’s design without being a functional chamber. Ancient Egyptian buildings often incorporated symbolic spaces that weren’t meant for human access. The void might relate to religious beliefs about the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife, or represent an architectural statement whose meaning has been lost. In this view, understanding the void would tell us something important about ancient Egyptian thought even if the space itself contained nothing material.

Hawass’s comments suggest the upcoming revelation will address these possibilities definitively, though he has been characteristically guarded about specifics. His involvement is significant: as Egypt’s most prominent archaeologist and a figure known for both spectacular discoveries and occasional controversy, Hawass brings both expertise and drama to archaeological announcements. His confidence that the void’s purpose will be revealed in 2026 suggests either that additional scanning has produced definitive evidence or that physical exploration of the space is planned.

The Politics of Pyramid Access

Any discussion of pyramid research must acknowledge the complex politics surrounding access to these monuments. Egypt controls access to the pyramids, and Egyptian authorities have historically been cautious about international research projects, particularly those that might involve invasive investigation. The ScanPyramids project succeeded partly because its non-invasive approach aligned with Egyptian concerns about preserving the monuments while still advancing understanding.

The question of whether to physically access the void, if such access is even possible, involves considerations beyond pure archaeology. The Great Pyramid is among the most visited monuments in the world and a cornerstone of Egypt’s tourism industry. Any investigation that might damage the structure or alter its appearance carries significant economic as well as cultural risks. At the same time, the potential for a major discovery creates pressure to learn more, particularly if physical access might reveal artifacts or inscriptions that imaging technology cannot detect.

Hawass has historically balanced these considerations by advocating for Egyptian control of pyramid research while supporting careful investigation using the best available technology. His announcement suggests confidence that whatever investigation has occurred or is planned meets Egyptian standards for responsible monument treatment. Whether this means additional non-invasive scanning, carefully designed physical exploration, or some combination remains to be seen.

The timing of the announcement also connects to broader discussions about Egypt’s archaeological heritage and its presentation to the world. The America 250 semiquincentennial has prompted reflection on how nations construct historical narratives through monuments and commemorations. Egypt’s pyramids have long served a similar function, representing a connection to ancient greatness that modern Egypt invokes for national identity and international prestige. A major new pyramid discovery would reinforce this connection at a moment when the world’s attention is focused on historical anniversaries and their meanings.

The Bigger Picture

The void inside the Great Pyramid represents more than an archaeological curiosity. It’s a test case for how modern technology can reveal secrets that remained hidden for millennia, and for how we should approach those revelations when they arrive.

The muon tomography that detected the void represents a broader trend toward non-invasive investigation of archaeological sites. Similar techniques have been used to discover chambers in other Egyptian monuments, hidden tunnels in ancient Mexican pyramids, and buried structures at sites around the world. This technology promises to reshape archaeology, allowing researchers to understand what lies beneath or within without the destructive excavation that characterized earlier eras. The Great Pyramid discovery will likely accelerate adoption of these techniques globally.

The mystery also reminds us how much remains unknown about even the most studied monuments. The Great Pyramid has been examined, mapped, and analyzed for centuries. It’s been explored by everyone from Roman tourists to Napoleonic scholars to modern scientists with the most advanced equipment available. Yet a 30-meter void escaped detection until 2017, hidden in plain sight above one of the pyramid’s best-known passages. This suggests that other ancient monuments may harbor similar surprises, waiting for technology sophisticated enough to reveal them.

Whatever the void turns out to be, its discovery connects to enduring questions about human achievement and its limits. The pyramid builders created a monument that has stood for 45 centuries, outlasting every civilization that has encountered it. They left no written records explaining their methods or purposes, forcing later generations to piece together understanding from the physical evidence alone. The void represents one more piece of that puzzle, a message from ancient builders that we’re only now learning to read. Like pivotal historical events that shaped our world, this discovery invites us to reconsider what we thought we knew and to remain humble about what we might still learn.

The announcement that answers are coming in 2026 creates both anticipation and responsibility. When the revelation arrives, it will need to be evaluated carefully, with attention to what the evidence actually shows rather than what we might hope it shows. The history of pyramid research includes plenty of spectacular claims that later proved unfounded. Whatever Hawass and his colleagues announce will deserve the same scrutiny, and the same openness to surprise, that the initial void detection received. The Great Pyramid has kept its secrets for millennia. Learning them will require patience as well as technology.