Before coffee reached Europe in the 17th century, the most common breakfast beverage across the continent was beer. This wasn’t because Europeans were particularly fond of morning intoxication. It was because beer was safe to drink. The brewing process killed the pathogens that lurked in water supplies, making weak ale a practical choice for hydration. The result was a continent that started each day slightly drunk, worked through the afternoon with diminishing buzz, and went to bed early because candles were expensive and there wasn’t much else to do.

Then coffee arrived, and something shifted. Here was a drink made with boiled water, which killed pathogens just as effectively as brewing, but with an entirely different effect on the mind. Instead of sedation, alertness. Instead of fuzzy contentment, sharpened focus. Some historians argue that this simple substitution, from depressant to stimulant, helped enable one of the most consequential intellectual movements in human history: the Enlightenment.

The claim sounds grandiose, perhaps absurdly so. Can a beverage really reshape civilization? The evidence suggests the relationship is more than coincidence. Coffee didn’t cause the Enlightenment any more than printing caused the Reformation, but like printing, it created conditions that made transformative change more likely. The story of how a bitter bean from Ethiopia helped fuel the Age of Reason is a reminder that history often turns on seemingly small hinges.

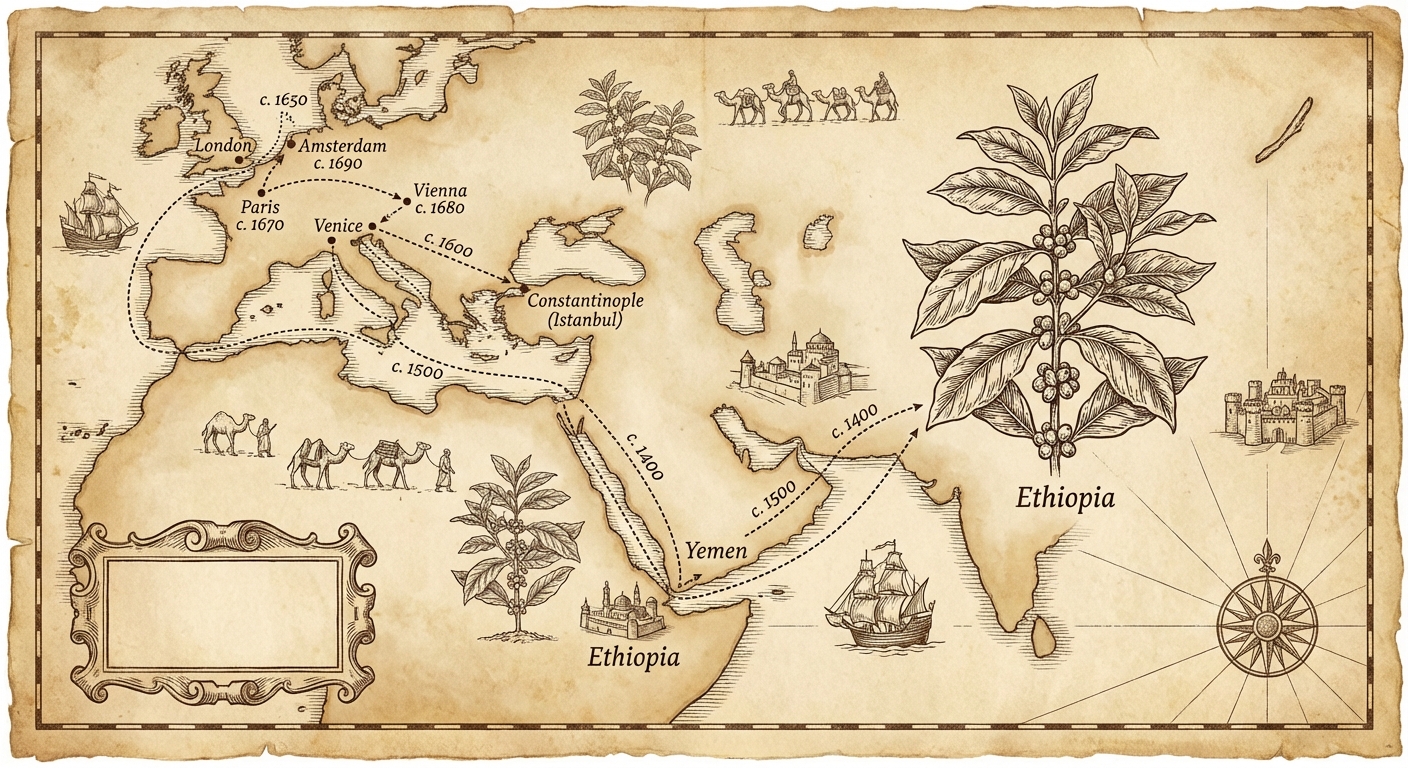

From Ethiopia to Arabia to Europe

Coffee’s journey began in the highlands of Ethiopia, where legend holds that a goat herder named Kaldi noticed his animals became unusually energetic after eating certain berries. Whether or not the story is true, coffee cultivation was well established in Yemen by the 15th century. Sufi monks used it to stay awake during nighttime prayers, and the drink spread through the Islamic world along trade routes and pilgrimage paths.

The first European accounts of coffee came from travelers to the Ottoman Empire, who described a black, bitter drink that kept people alert and talkative. Venetian traders brought beans back to Italy in the early 1600s, and the drink spread rapidly northward. Some Christian clergy initially opposed it as a “Muslim drink,” but Pope Clement VIII reportedly tasted it and declared it so delicious that it would be a sin to let only infidels enjoy it. With papal approval secured, coffee’s conquest of Europe began in earnest.

The speed of adoption was remarkable. The first coffeehouse in England opened in Oxford in 1650, followed by London in 1652. By 1700, London alone had over 3,000 coffeehouses. Paris, Vienna, Amsterdam, and cities across Europe developed their own coffee cultures, each with distinct characteristics but sharing one crucial feature: coffeehouses became places where people gathered specifically to think, debate, and exchange ideas.

The Coffeehouse as Intellectual Incubator

What made coffeehouses different from taverns wasn’t just the beverage. It was the entire social architecture. Taverns were for relaxation, escape, and the lowering of inhibitions. Coffeehouses were for alertness, engagement, and the sharpening of arguments. The drink itself enforced this distinction: coffee made it harder to blur the edges of disagreement, harder to let sloppy thinking slide.

The coffeehouses of 17th and 18th century Europe operated on remarkably egalitarian principles for their time. A penny bought admission and a cup of coffee, earning these establishments the nickname “penny universities.” Inside, social hierarchies softened. Merchants sat alongside aristocrats. Scientists debated with poets. The price of entry was not birth or title but the ability to hold up your end of a conversation.

Different coffeehouses developed different specialties and clienteles. In London, Lloyd’s Coffee House attracted ship captains, merchants, and insurers discussing maritime risk, eventually evolving into Lloyd’s of London, the insurance giant. Jonathan’s Coffee House in Exchange Alley became a gathering place for stock traders, later formalized as the London Stock Exchange. Scientists gathered at the Grecian Coffee House, where Isaac Newton reportedly dissected a dolphin on the premises. The Royal Society, founded in 1660, held early meetings in coffeehouses before acquiring permanent quarters.

This clustering effect mattered enormously. Ideas spread faster when the people generating them are in regular contact. The coffeehouse created a new kind of public sphere, a space between private life and official institutions where ideas could be debated, refined, and circulated among engaged citizens. The philosopher Jürgen Habermas identified the coffeehouse as central to the emergence of what he called the “bourgeois public sphere,” the space of rational debate that made democratic politics conceivable.

The Chemistry of Clear Thinking

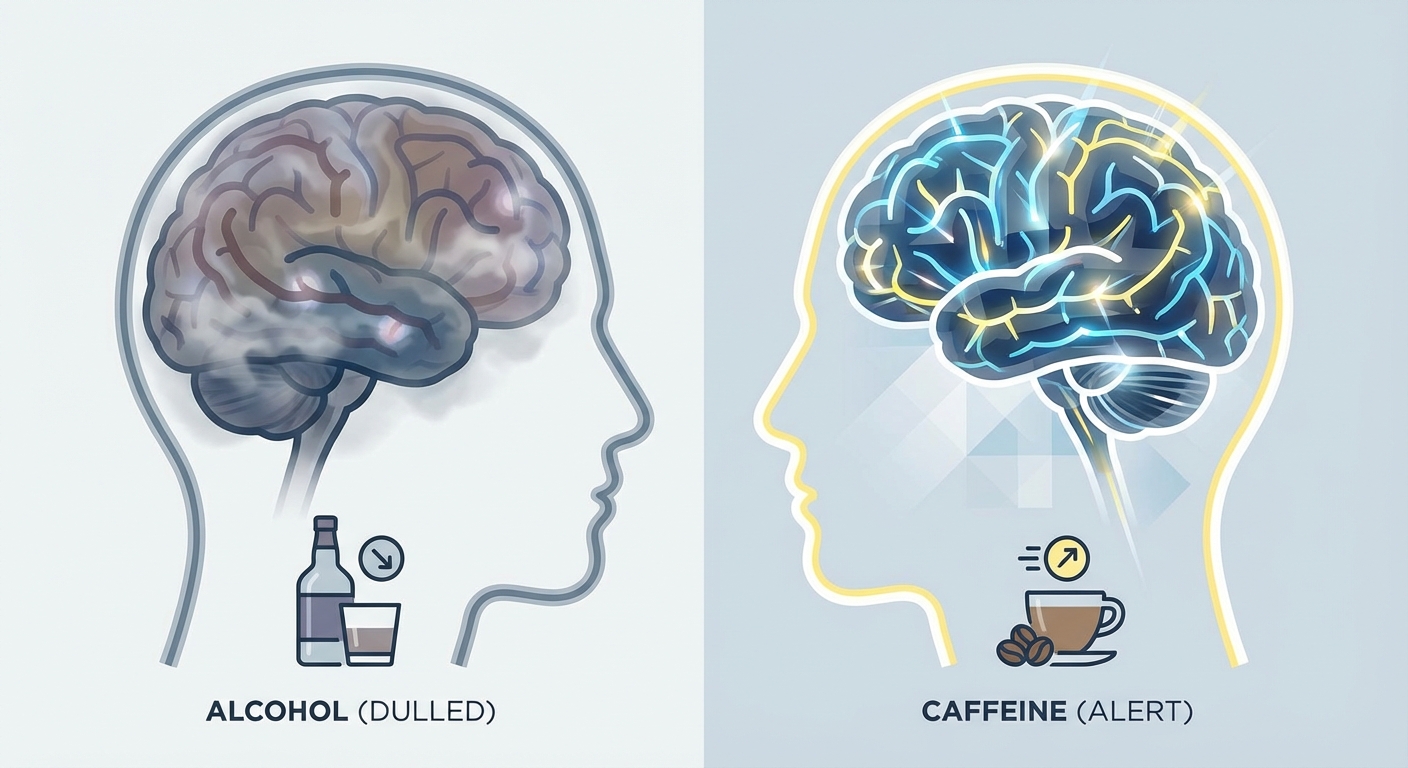

The social architecture of coffeehouses mattered, but so did the pharmacology. Caffeine is a remarkable molecule. It works by blocking adenosine receptors in the brain. Adenosine is a neurotransmitter that accumulates during waking hours and promotes sleepiness. By preventing adenosine from binding to its receptors, caffeine delays fatigue and maintains alertness.

But caffeine does more than just keep you awake. It enhances certain cognitive functions, particularly those involving sustained attention, vigilance, and working memory. Studies show that caffeine improves performance on tasks requiring concentration and reduces the subjective feeling of mental effort. For intellectuals attempting to work through complex arguments or write extended treatises, these effects were genuinely useful.

The contrast with alcohol is stark. Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant that impairs judgment, reduces inhibition, and degrades cognitive function. A culture that began its day with ale and ended it with wine was not optimally configured for rigorous thinking. The switch to coffee didn’t make everyone a genius, but it shifted the baseline state of minds engaged in intellectual work.

Consider the sheer output of Enlightenment thinkers. Voltaire reportedly drank 50 cups of coffee a day and produced a staggering volume of work: plays, histories, philosophical treatises, and over 20,000 letters. While 50 cups is almost certainly exaggerated, the association between coffee and productivity became a trope of the era. Balzac, slightly later, described his coffee consumption in almost mystical terms: “Coffee sets the blood in motion and stimulates the muscles; it accelerates the digestive processes, chases away sleep, and gives us the capacity to engage a little longer in the exercise of our intellects.”

Ideas That Changed in Coffee-Soaked Air

Tracing direct causal links between coffee consumption and specific Enlightenment ideas would be overreach. But we can observe that many foundational Enlightenment concepts emerged from or were refined in coffeehouse culture. The idea that knowledge should be accessible to all, not hoarded by elites, aligned perfectly with the penny university model. The emphasis on reason over tradition reflected the sober, argumentative atmosphere of the coffeehouse as opposed to the deferential culture of the court.

The emergence of newspapers and journals was intimately connected to coffeehouse culture. The first English daily newspaper, The Daily Courant, launched in 1702 and was sold primarily in coffeehouses. Joseph Addison and Richard Steele published The Spectator from 1711 to 1712, a publication explicitly designed to bring philosophy out of academic closets “and libraries, schools, and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea tables and coffeehouses.” The idea that public opinion mattered, that informed citizens debating in public spaces could and should influence governance, was radical. Coffeehouses provided both the venue for such debates and the stimulant that kept debaters sharp.

In France, the Café Procope, established in 1686, became a gathering place for philosophes including Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot. The Encyclopédie, that monument of Enlightenment ambition to compile all human knowledge, was planned in conversations at Procope and similar establishments. When the French Revolution came, it was in the cafés that conspirators met and orators practiced their speeches before taking them to the streets.

The Counterargument and the Bigger Picture

Skeptics might point out that correlation isn’t causation. The Enlightenment had many causes: the Scientific Revolution, the Protestant Reformation, increased literacy, expanding commerce, and contact with other cultures through exploration and trade. Coffee arrived alongside these other transformations and may simply have been along for the ride.

This objection has merit. No serious historian would argue that coffee caused the Enlightenment in any simple sense. But the objection misses the more interesting point. Historical causation is rarely simple. Transformative changes usually require multiple factors aligning: material conditions, ideas, institutions, and technologies that amplify human capacities. Coffee and coffeehouses were part of an ecology of innovation that also included printing, postal services, scientific instruments, and new forms of commercial organization.

What coffee provided was an enhancement to human cognitive capacity that arrived at precisely the moment when that capacity was being deployed in new ways. It offered a social institution, the coffeehouse, that modeled and practiced the Enlightenment ideals of open debate and the free exchange of ideas before those ideals were fully articulated. It demonstrated that a simple change in daily habits could have far-reaching consequences for how societies think and organize themselves.

The Bigger Picture

The story of coffee and the Enlightenment invites us to think about how material conditions shape intellectual life. We often treat ideas as free-floating entities, evaluated purely on their merits, transmitted through texts and debates. But ideas emerge from embodied minds, and those minds are affected by what we consume, where we gather, and how alert we are when we think.

Today, caffeine remains the world’s most widely used psychoactive substance. Coffee shops have enjoyed a renaissance as places for remote work and informal meetings, echoing their historical role as alternatives to both home and office. The technology has changed, but the basic formula persists: a stimulating beverage, a public space, and people gathering to think and work.

Whether coffee actually changed history or merely accompanied change, the question itself illuminates something important about how civilizations transform. Grand movements like the Enlightenment don’t emerge from nowhere. They require infrastructure, both physical and chemical. They need spaces where new ideas can be tried out and refined. They benefit when minds engaged in the work are alert rather than sedated.

The next time you order a coffee, you’re participating in a tradition that stretches back centuries. The drink in your hand is connected, through history and culture and pharmacology, to some of the most consequential changes in how humans think about themselves and their world. It’s a lot to put on a simple beverage, but coffee has never been just a drink. It’s been a catalyst, a social lubricant, and a tool for sharpening minds. The Enlightenment thinkers who gathered in Europe’s coffeehouses understood this, even if they couldn’t have articulated it in terms of adenosine receptors and neurotransmitters. They knew that what they drank affected how they thought, and they chose accordingly.