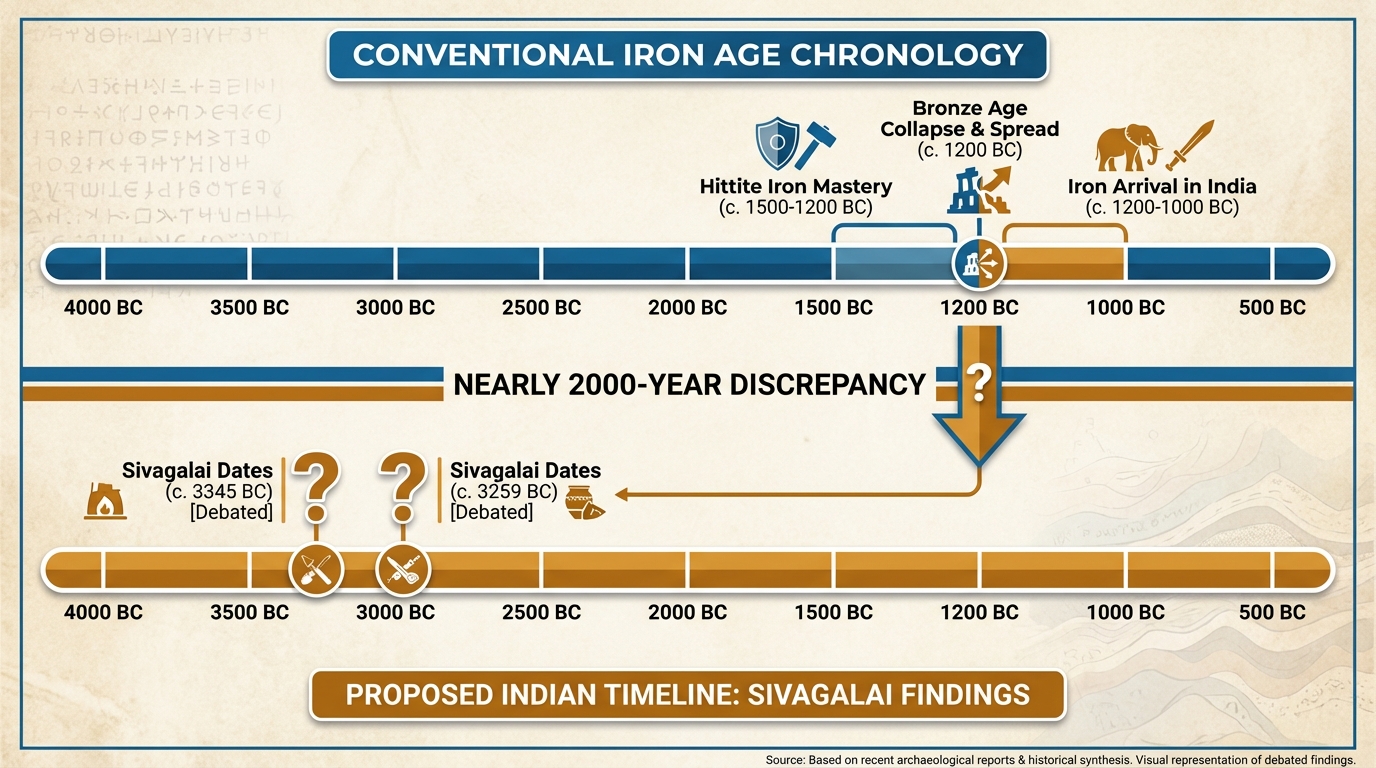

The textbooks tell a clear story: the Iron Age began in Anatolia around 1200 BC when the Hittite Empire fell and its ironworking secrets spread across the ancient world. Iron reached India through gradual diffusion from the Near East, arriving somewhere between 1200 and 1000 BC. This timeline has been accepted for generations, forming the backbone of how we understand the development of civilization.

A discovery in southern India is challenging that entire narrative. Archaeological excavations at Sivagalai in Tamil Nadu have yielded carbon dates that, if confirmed, would push the Indian Iron Age back to approximately 3345 BC, nearly two thousand years before the conventional starting point for iron technology anywhere in the world. The implications are staggering: India may not have received iron technology from the West. India may have invented it independently.

The finding has ignited intense debate among archaeologists and historians. Some see it as revolutionary evidence that ancient India developed advanced metallurgy far earlier than previously believed. Others urge caution, noting that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence and that isolated carbon dates can be misleading. What’s not in dispute is that something significant is emerging from the red soil of Tamil Nadu, something that demands we reconsider how technology spread across the ancient world.

The Sivagalai Excavation

Sivagalai sits in the Thoothukudi district of Tamil Nadu, a region that has become increasingly important to archaeologists studying ancient South Indian civilization. The site contains burial urns, the distinctive megalithic funerary containers used across South India for thousands of years. These urns have been found at sites throughout the region, often containing human remains, pottery, and iron artifacts.

What makes Sivagalai exceptional is what researchers found when they carbon-dated charcoal samples associated with iron objects from the burial urns. Two samples returned dates of approximately 3345 BC and 3259 BC. If these dates are accurate and if the iron artifacts are genuinely associated with those dated materials, iron technology in southern India would predate the Hittite Empire by nearly two millennia.

The Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology has conducted extensive excavations at the site, recovering not just the dated materials but a broader assemblage of artifacts that paint a picture of a sophisticated ancient society. Iron implements, distinctive pottery styles, and evidence of agricultural practices all point to a complex civilization that flourished in this region during an era that mainstream archaeology has traditionally considered prehistoric.

The Conventional Timeline

To understand why the Sivagalai dates are so controversial, it helps to know the accepted story of how iron technology developed. Iron is everywhere on Earth, but turning it into useful metal is extraordinarily difficult. Unlike copper and bronze, which melt at temperatures achievable with simple furnaces, iron requires both higher temperatures and a sophisticated understanding of how to remove impurities and add carbon to create workable steel.

The Hittites of Anatolia, modern-day Turkey, are traditionally credited as the first people to master iron smelting on a significant scale. Their empire controlled the technology jealously, using iron weapons as a strategic advantage over bronze-armed rivals. When the Hittite Empire collapsed around 1200 BC during the Bronze Age Collapse, their ironworking knowledge spread across the Mediterranean and eventually reached India through trade and migration.

This diffusion model has been the standard explanation for decades. Iron technology developed once, in one place, and spread from there. Every Iron Age culture descended, technologically speaking, from the Hittites. The model is elegant, well-supported by archaeological evidence from the Near East and Mediterranean, and forms the foundation of how we understand ancient technological development.

The Sivagalai dates don’t fit this model at all.

Evidence and Controversy

Archaeological dating is complicated, and the Sivagalai findings have prompted healthy skepticism from many researchers. Carbon dating measures the decay of radioactive carbon in organic materials like charcoal, but it tells you only how old the charcoal is, not necessarily how old the artifacts found near it are. Stratigraphic mixing, where materials from different time periods become jumbled together, can create misleading associations.

Critics point out that the Sivagalai dates remain outliers. Other Indian archaeological sites have produced Iron Age dates consistent with the conventional timeline, placing iron technology in the subcontinent between 1200 and 800 BC. A single site with anomalous dates, however dramatic, doesn’t overturn decades of accumulated evidence. Science requires replication, and the Sivagalai findings need to be confirmed at other sites before they can be considered definitive.

Supporters of the early dates counter that Tamil Nadu has consistently produced archaeological surprises that challenge conventional timelines. The Keeladi excavation, another Tamil Nadu site, pushed back the date of urban civilization in the region by several centuries and demonstrated that literate, sophisticated societies existed in South India far earlier than previously recognized. Perhaps Sivagalai is another such site, revealing capabilities that mainstream archaeology simply hasn’t been looking for.

A Broader Pattern

The Sivagalai discovery exists within a larger context of archaeological findings that are rewriting the history of ancient India. For much of the twentieth century, the dominant narrative positioned India as a receiver of technology and culture from the West, with major innovations diffusing from Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean into the subcontinent.

Recent discoveries have complicated that picture. The Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished from roughly 3300 to 1300 BC, demonstrates that sophisticated urban societies developed in India independently of Western influence. Excavations at Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, and other sites have revealed advanced urban planning, standardized weights and measures, and engineering capabilities that rival anything in the ancient Near East.

The question of iron technology fits into this broader debate. If India developed iron smelting independently, it would suggest the subcontinent was a center of technological innovation rather than merely a recipient of innovations developed elsewhere. Multiple independent inventions of iron technology would also change how we understand technological development more generally, replacing a single-origin diffusion model with a picture of parallel innovation across different civilizations.

What This Means

The debate over the Sivagalai dates won’t be resolved quickly. Archaeological controversies of this magnitude take years or decades to settle, as researchers examine and re-examine evidence, conduct new excavations, and develop improved dating techniques. The scientific process is slow precisely because getting history right matters.

But even before the debate is settled, the Sivagalai discovery accomplishes something important: it forces us to question assumptions we may not have realized we were making. The conventional Iron Age timeline wasn’t just a neutral description of how technology spread. It embedded assumptions about which civilizations were innovative and which were derivative, which were centers of development and which were peripheries receiving innovations from elsewhere.

Those assumptions may be wrong. The ancient world may have been more multipolar than we realized, with major technological advances occurring independently in multiple places. India’s role in that story may be larger than textbooks have traditionally acknowledged. Whether or not the specific Sivagalai dates hold up, the questions they raise are worth asking.

The Bigger Picture

A charcoal sample from a burial urn in Tamil Nadu has become the center of a debate that extends far beyond archaeology. At stake is how we understand the ancient world: as a place where technology spread from a few centers of innovation to everywhere else, or as a more complex landscape where multiple civilizations developed advanced capabilities independently.

The conventional story of the Iron Age made sense when we knew less about ancient India. It made sense when Western archaeologists dominated the field and naturally looked first to the Near East and Mediterranean for the origins of technology. It may still turn out to be correct. But Sivagalai reminds us that the conventional story was always a hypothesis, not a fact, and that hypotheses must be tested against evidence wherever that evidence is found.

Whatever the final verdict on the Sivagalai dates, South Indian archaeology has entered a period of extraordinary discovery. Sites across Tamil Nadu are revealing civilizations more complex, more ancient, and more technologically sophisticated than previous generations of scholars imagined. The red soil of Tamil Nadu still holds secrets, and some of those secrets may change how we understand not just India but the entire ancient world.

Sources: Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology excavations, carbon dating analysis of Sivagalai burial urn assemblages, Keeladi excavation findings, comparative Iron Age chronology research, Indus Valley Civilization archaeological studies.