Professor Rustem Aslan brushed away centuries of accumulated soil and found himself staring at the past. Spread across a narrow strip of ground just outside what had once been palace walls were dozens of polished clay spheres, each about the size of a golf ball. They were sling stones, ammunition for one of the deadliest weapons of the Bronze Age. Mixed among them lay corroded bronze arrowheads and the fragmented remains of human skeletons buried in obvious haste. The destruction layer dated to roughly 1200 BC, precisely when ancient Greek historians claimed the Trojan War took place.

The 2025 excavation season at Troy, the UNESCO World Heritage site in northwestern Turkey, has produced what may be the most compelling physical evidence yet that Homer’s Iliad describes real events. After more than a century of archaeological investigation, we may finally be able to say with confidence: something very much like the Trojan War actually happened.

A War Lost to Legend

The question of whether the Trojan War was historical has haunted scholars since the modern era of archaeology began. Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations at Hisarlik in the 1870s revealed that a major Bronze Age city had indeed existed where ancient sources placed Troy. But finding a city and proving a specific war are very different things.

Homer’s Iliad, composed around the 8th century BC but describing events supposedly four centuries earlier, tells of a ten-year siege by Greek forces seeking to recover Helen, wife of King Menelaus, who had been abducted by the Trojan prince Paris. The story features gods intervening in battle, heroes performing superhuman feats, and a final victory achieved through the deception of the wooden horse. Separating potential historical memory from literary embellishment has proven extraordinarily difficult.

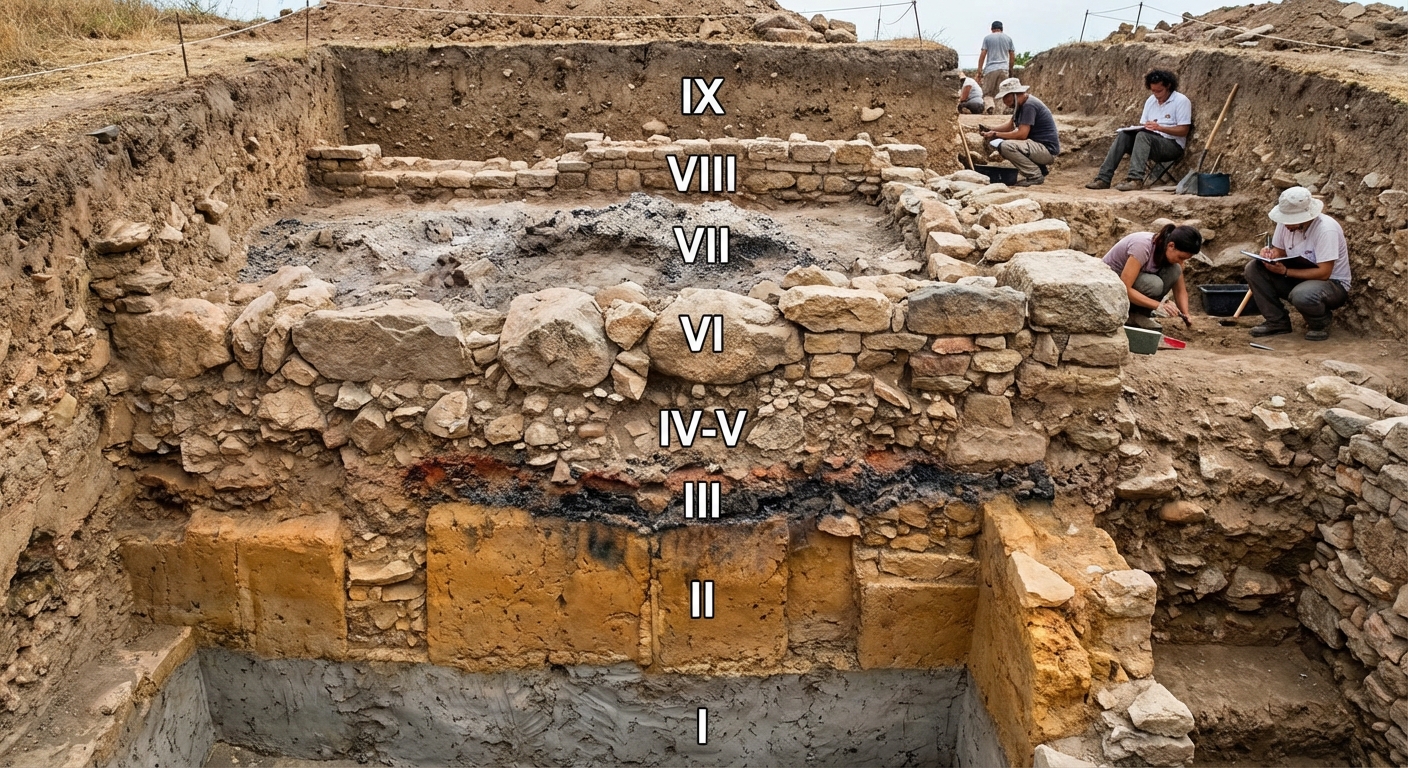

The archaeological record at Troy itself has complicated matters. The site contains multiple layers of occupation spanning thousands of years, labeled Troy I through Troy IX. Which layer, if any, corresponds to Homer’s city? Early excavators favored Troy II, which showed signs of destruction and wealth. Later research shifted attention to Troy VI and VII, which date to the Late Bronze Age when Mycenaean Greeks would have been capable of mounting the kind of military expedition Homer describes.

Troy VIIa, destroyed around 1180 BC, has long been the leading candidate. Excavations led by Carl Blegen in the 1930s and Manfred Osman Korfmann in the 1980s revealed a burnt destruction layer, skeletons, and weapons within this stratum. But the evidence remained circumstantial. Cities burned for many reasons in the ancient world. The presence of weapons and bodies suggested violence but didn’t prove a Greek siege.

The 2025 Discoveries

The 2025 excavation season, led by Professor Aslan of Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University and supported by the Turkish Culture and Tourism Ministry, focused specifically on accessing the destruction layer of the Late Bronze Age. What they found exceeded expectations.

The concentration of sling stones is particularly significant. These weren’t scattered randomly across the site; they were clustered in a small area just outside the palace walls, exactly where defenders would have positioned themselves against an attacking force. The stones themselves were carefully crafted, polished clay spheres designed for lethal precision. Bronze Age slings were devastating weapons capable of cracking skulls and penetrating basic armor. A trained slinger could strike targets over a hundred meters away.

The positioning of the finds tells a story. “The fact that so many sling stones were uncovered in such a small area in front of the palace points to an activity related to defense or assault,” Aslan explained to reporters. Either the city’s defenders were firing outward at attackers, or attacking forces were bombarding the palace walls. Either way, the concentration indicates organized military action, not random violence.

The arrowheads support this interpretation. Found near the palace and city walls, they date to the same destruction layer as the sling stones. The charred buildings indicate widespread fire. The hastily buried skeletons suggest people dying faster than survivors could properly inter them. Put together, the picture is one of a city under siege, fighting desperately and ultimately losing.

The dating is crucial. The destruction layer corresponds to roughly 1200 to 1180 BC. Ancient Greek historians, working from genealogies and astronomical calculations, dated the fall of Troy to 1184 BC. Eratosthenes, the scholar who first calculated Earth’s circumference, placed the war at 1194 to 1184 BC. The archaeological evidence now aligns with remarkable precision with these traditional dates.

The Bronze Age Collapse

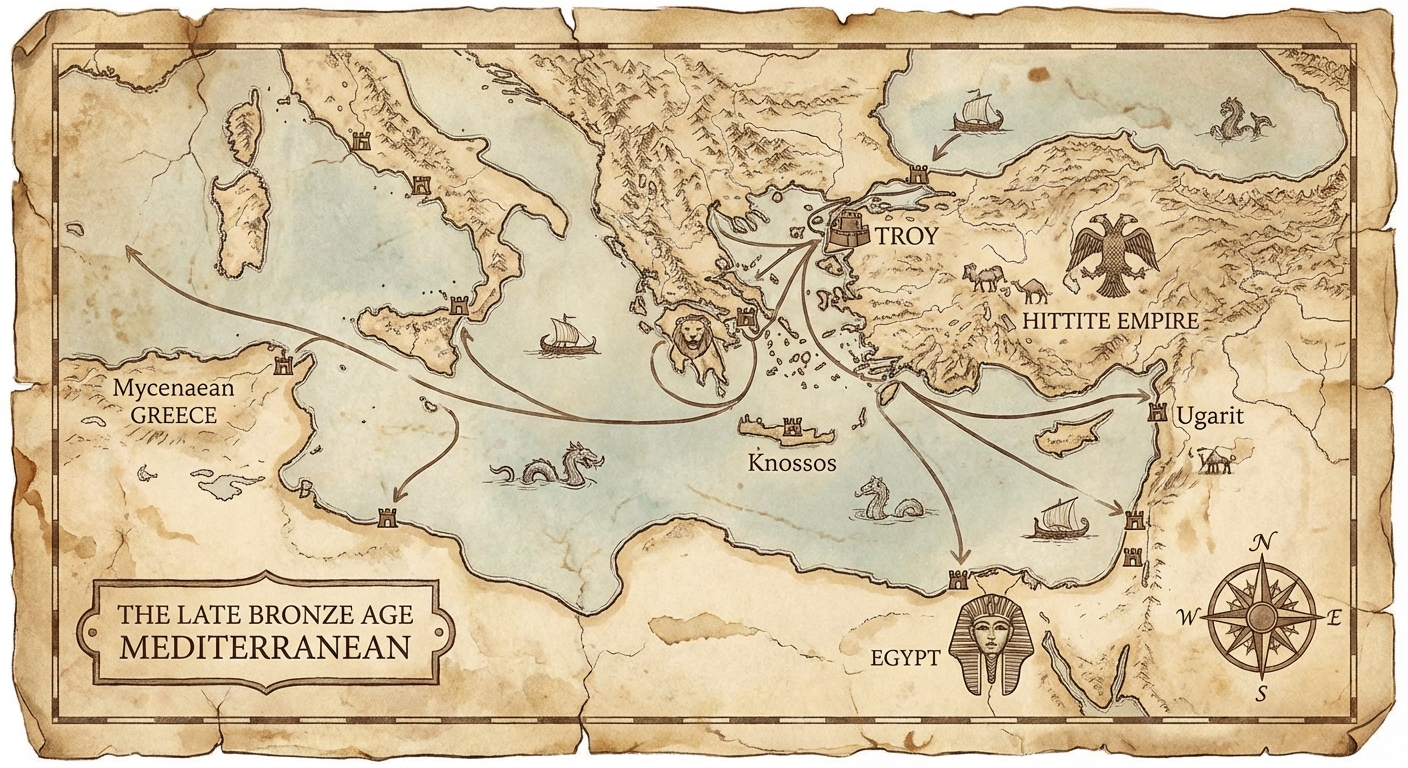

To understand why the Trojan War might have happened, we need to understand the world that was ending around 1200 BC. The Late Bronze Age was an era of interconnected empires stretching from Egypt to Mesopotamia, from the Aegean to Anatolia. Trade networks linked distant cities. Diplomatic correspondence flowed between royal courts. The great powers of the age, Egypt, the Hittites, Assyria, Babylon, and the Mycenaean Greeks, maintained complex relationships of alliance and rivalry.

Then, within a few decades, this entire system collapsed. The Hittite Empire, which had dominated Anatolia for centuries, fragmented under the strain of famine, plague, and civil war. Mycenaean palace centers in Greece burned. Cities across the eastern Mediterranean were destroyed or abandoned. Egypt barely survived, and never recovered its former power. The Mediterranean world entered a “Dark Age” that lasted nearly half a millennium.

The causes of this collapse remain debated. Climate change may have triggered famines. Earthquakes devastated some regions. The mysterious “Sea Peoples” attacked coastal cities from Egypt to the Levant. Internal rebellions may have toppled weakened governments. Most likely, multiple factors reinforced each other in a cascading failure of interconnected systems.

Troy sat at a crucial junction in this collapsing world. The city controlled the Dardanelles, the narrow strait connecting the Mediterranean to the Black Sea. Any ships trading between Greece and the grain-rich lands around the Black Sea had to pass Troy. In an era of failing harvests and desperate hunger, control of this chokepoint was worth fighting for.

What Hittite Texts Reveal

Perhaps the most intriguing corroboration comes not from Greek sources but from the archives of the Hittite Empire. Clay tablets discovered in the Hittite capital Hattusha (modern Bogazkoy in Turkey) mention a powerful city near the Dardanelles called Wilusa. Linguists have connected this name to Ilios, the Greek name for Troy. The match isn’t coincidental; it reflects how the same city name evolved in different languages.

The tablets reveal several striking details. Wilusa was important enough to warrant diplomatic attention from the Hittite great kings. One tablet records a treaty between the Hittite king and a ruler of Wilusa named Alaksandu. This name corresponds closely to Alexander, which Homer gives as the birth name of Paris, the Trojan prince whose abduction of Helen sparked the war.

Other Hittite texts mention “Ahhiyawa,” which scholars identify as a reference to the Achaeans, Homer’s term for the Greeks who besieged Troy. The tablets show that the Hittites viewed Ahhiyawa as a significant power capable of interfering in Anatolian affairs. They record disputes over coastal territories and concerns about Ahhiyawan military activities.

The Hittite evidence doesn’t describe the Trojan War directly. No tablet has been found saying “the Ahhiyawans attacked Wilusa.” But the texts confirm that the basic elements of Homer’s story were real: a major city near the Dardanelles, Greek involvement in the region, and political tensions that could plausibly have escalated to war. The Iliad’s setting, if not its specific narrative, reflects genuine Bronze Age geography and politics.

Separating History from Epic

If the Trojan War was real, how much of Homer’s account can we trust? This question requires careful thinking about how oral traditions preserve and transform historical memory.

Homer composed the Iliad roughly four centuries after the events it describes. He was working with oral traditions that had been passed down through generations of bards, each adding, embellishing, and adapting the stories for their audiences. The poems clearly contain anachronisms, such as references to iron weapons that weren’t common in the Bronze Age, alongside accurate details about Mycenaean warfare that couldn’t have been known without genuine memory of the period.

Many scholars now believe the Iliad represents a fusion of multiple historical events compressed into a single narrative. There may have been a siege of Troy. There may also have been other conflicts between Greeks and Anatolian cities. The story of Helen’s abduction may be a poetic explanation for a war whose real causes were economic or political. The ten-year duration is almost certainly literary convention rather than historical fact.

The intervention of gods poses obvious problems for historical interpretation. Yet even here, we might see echoes of reality. Ancient peoples attributed natural phenomena and unexpected reversals of fortune to divine agency. A plague that devastated an army camp, as Apollo’s arrows devastate the Greeks in the Iliad, was a real possibility in Bronze Age warfare. A sudden storm that aided one side or another could easily be remembered as divine intervention.

What the archaeological evidence increasingly suggests is that Homer’s audience would have recognized the Trojan War as a genuine historical event, not pure fiction. The epic exaggerated, mythologized, and dramatized, but it was rooted in real places, real peoples, and real conflicts. This makes the Iliad something remarkable: literary imagination built on historical memory, preserving truths about a vanished world that formal history failed to record.

The Bigger Picture

The 2025 Troy excavations add to a growing body of evidence that ancient myths often contain historical cores. We’ve seen this pattern before. The biblical city of Jericho, long dismissed as legendary, turned out to be real. The hidden chambers of the Great Pyramid have revealed secrets that ancient texts hinted at. The Minoan civilization, remembered in Greek myth as the kingdom of King Minos and his labyrinth, emerged as archaeological reality in the early 20th century.

This doesn’t mean we should read myths as straightforward history. The Iliad isn’t a war diary. The sling stones at Troy don’t prove that Achilles dragged Hector’s body around the city walls. But the divide between “myth” and “history” may be less absolute than modern categories suggest. Ancient peoples remembered their past through stories, and those stories, however transformed, carried genuine information about events, places, and peoples.

The Trojan War’s reality also matters for understanding the Bronze Age Collapse itself. Much like Roman lead poisoning may have contributed to a later empire’s decline, environmental and material factors shaped the Bronze Age world in ways we’re only beginning to understand. If Mycenaean Greeks attacked Troy around 1180 BC, they were doing so at the very moment their own civilization was beginning to fail. The war may have been one of the last gasps of Mycenaean power, a desperate grab for resources and strategic position in a world falling apart. Within a generation, the palace centers that had sent ships to Troy would themselves be destroyed.

For modern readers, the excavations offer something beyond academic interest. The Iliad has shaped Western literature for nearly three millennia. Its themes of honor, loss, and the tragedy of war resonate because they speak to permanent aspects of human experience. Knowing that these themes emerged from genuine historical trauma adds depth to the poetry. Achilles’ rage, Hector’s doomed defense of his city, Priam’s grief for his fallen son: these were not merely imaginative creations. They were attempts to make sense of real catastrophe, to find meaning in the destruction of a world.

The archaeological work continues. Professor Aslan’s team plans further excavations to access deeper parts of the destruction layer. They’re looking for more weapons, more human remains, more evidence of the siege’s progress and the city’s final hours. Each discovery adds detail to a picture that’s becoming increasingly clear: about 3,200 years ago, Greek warriors sailed to Troy and brought it down. Homer remembered. Now, finally, we have proof.