For over two thousand years, scholars have debated whether Homer’s Iliad describes real events or pure mythology. The epic poem tells of a decade-long Greek siege of Troy, fought over Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world. Gods intervene in battles. Heroes perform impossible feats. The whole narrative reads like mythology because, most academics assumed, that’s exactly what it is.

Then archaeologists found the sling stones. Thousands of them, concentrated outside the palace walls of Troy, dating to approximately 1200 BCE, the period when the Trojan War supposedly occurred. These weren’t decorative objects or religious offerings. They were weapons, piled in exactly the pattern you’d expect from a prolonged siege: ammunition expended against defensive walls, accumulating over months or years of assault.

Fresh excavations by Turkish archaeologists have uncovered evidence that transforms the debate. Arrowheads embedded in ancient walls. Buildings that show clear signs of catastrophic fire. Human remains buried hastily, without the careful preparation typical of Bronze Age funeral practices. Layer by layer, the archaeological record is revealing a city that died violently, in exactly the period and manner that Homer described.

What the Excavations Actually Found

The site of Troy, called Hisarlik in modern Turkey, has been excavated intermittently since Heinrich Schliemann first dug there in the 1870s. Schliemann was convinced he had found Homer’s Troy, but his methods were crude by modern standards, and subsequent generations of archaeologists have been more cautious in their claims. The site contains at least nine distinct settlement layers spanning three thousand years, making it difficult to identify which, if any, corresponds to Homer’s city.

The current excavations focus on Troy VIIa, a fortified settlement destroyed around 1190-1180 BCE. This date falls within the range that ancient Greek tradition assigned to the Trojan War, and the city shows unmistakable signs of violent destruction. But evidence of destruction isn’t evidence of the specific war Homer described. Cities burned for many reasons in the turbulent Late Bronze Age.

What makes the new discoveries compelling is their specificity. The sling stones aren’t scattered randomly; they’re concentrated in patterns consistent with siege warfare. Some were found embedded in defensive walls at angles indicating incoming fire. Others accumulated in the ground outside those walls, representing missed shots or ammunition that struck and fell. The distribution tells a story of sustained attack from a consistent direction.

The arrowheads show similar patterning. Bronze Age arrows weren’t casually discarded; bronze was valuable, and both attackers and defenders would typically recover spent ammunition. Finding arrowheads embedded in walls and scattered around attack positions suggests fighting intense enough that normal recovery wasn’t possible. Some arrowheads show damage patterns from striking stone, exactly as they would if fired at fortifications.

The Fire Layer That Changes Everything

Archaeological evidence of fire is common in ancient sites. Buildings burned accidentally, were destroyed by earthquakes and subsequent fires, or were deliberately torched during reconstruction. The fire damage at Troy VIIa is different. It shows characteristics of deliberate, systematic destruction: the kind of burning that happens when a conquering army wants to ensure a city can never rise again.

The fire layer extends across the entire settlement. Buildings that stood separate from each other all show simultaneous burning, a pattern inconsistent with accidental fire spreading from a single source. The intensity of the heat, visible in the vitrification of mud bricks and the fusion of bronze objects, indicates fires deliberately fed with fuel rather than allowed to burn naturally.

Most significantly, the fire happened after the city’s defensive capabilities had already been compromised. Walls show breach damage that predates the burning. Some structures collapsed from structural failure, not fire, suggesting they were undermined or battered before flames consumed them. The sequence of damage tells a story: first the siege, then the breach, then the destruction.

The human remains add another dimension. Normal Bronze Age burial practices involved elaborate preparation: bodies positioned carefully, grave goods arranged, funeral rites performed. The remains from Troy VIIa show none of this. Bodies were buried quickly, without ceremony, sometimes in positions suggesting they fell where they died. One skeleton showed an arrowhead embedded in the spine. These aren’t peaceful deaths followed by rushed burials. They’re casualties of violence.

Homer’s Historical Method

If the Trojan War was real, how much of Homer’s account reflects actual events? The Iliad was composed around 750 BCE, roughly 450 years after the events it describes. Could any historical memory survive that long, especially in a society that transmitted knowledge orally?

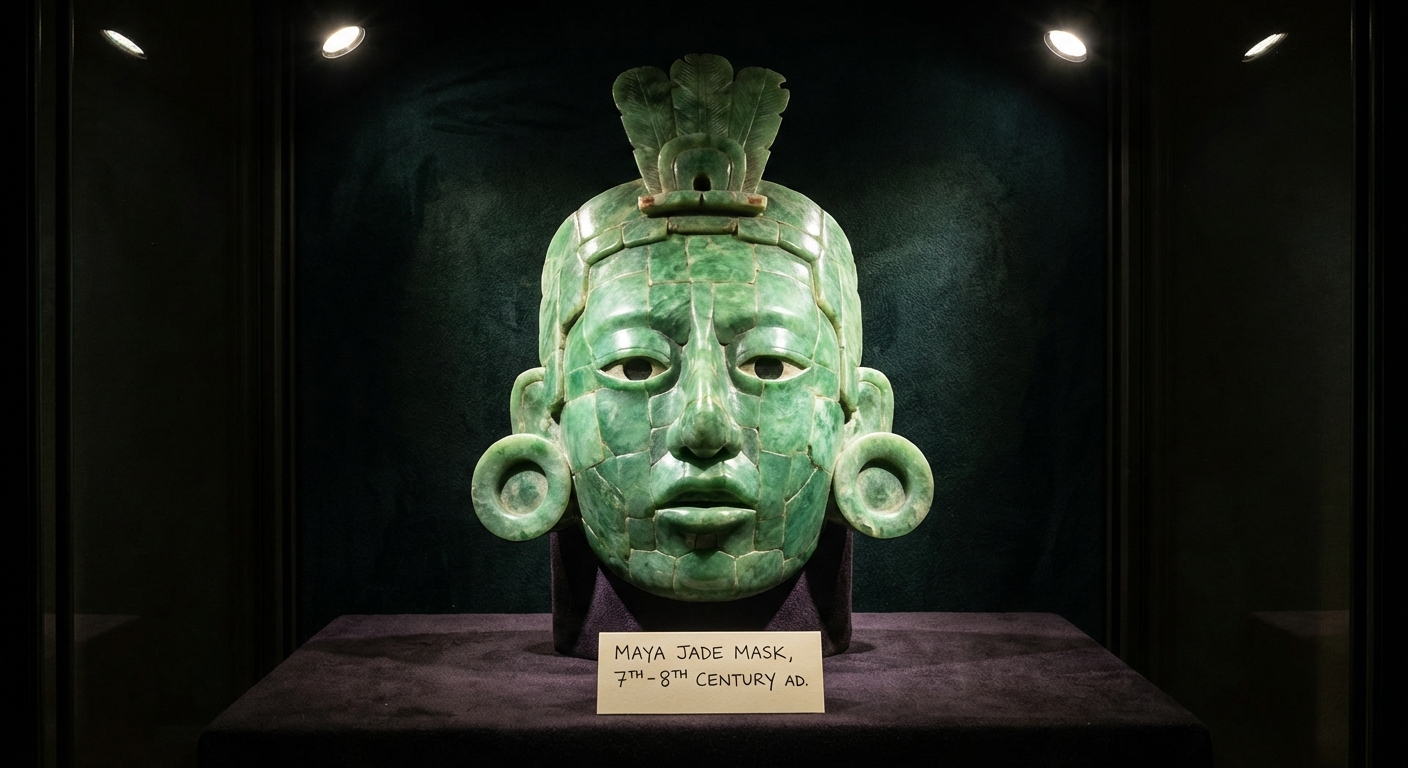

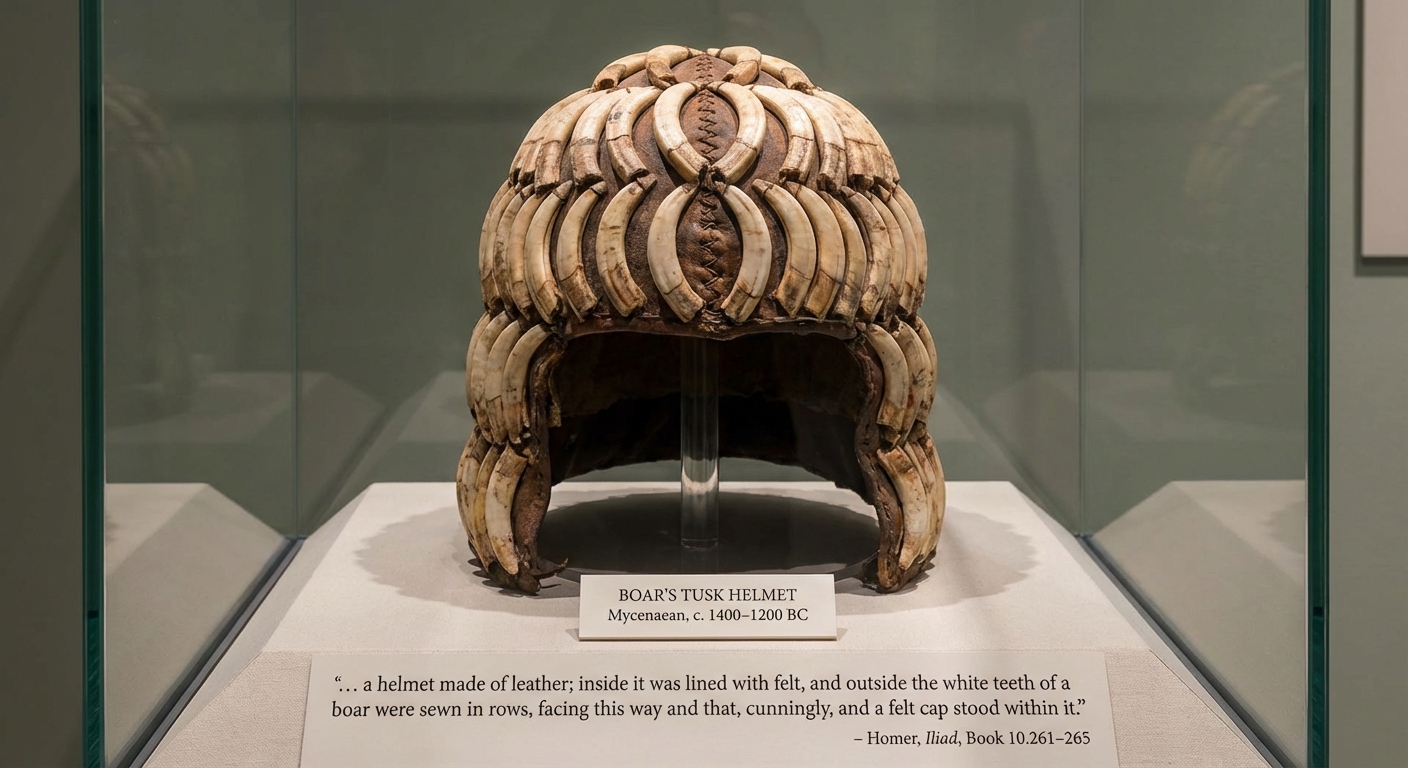

The answer appears to be yes, at least partially. The Iliad contains details that Homer couldn’t have known unless some authentic tradition reached him. The poem describes a specific type of bronze tower shield that was obsolete by Homer’s time but matches shields depicted in Late Bronze Age art. It mentions a boar’s tusk helmet, an archaic style that archaeological evidence confirms existed in the Mycenaean period but disappeared centuries before Homer wrote.

The catalog of ships in Book 2 of the Iliad lists contingents from across Greece, naming specific cities and their leaders. Many of these cities were major centers in the Late Bronze Age but insignificant or abandoned by Homer’s time. The list reads like a snapshot of Mycenaean political geography, information that would have been useless to Homer’s audience unless it was preserved as part of the traditional story.

These anachronisms suggest that the Iliad’s core narrative descends from accounts composed much closer to the events themselves. Oral poetry traditions are remarkably conservative; bards who altered traditional stories too freely lost their audiences. The authentic Bronze Age details embedded in Homer’s poem are best explained as fossils, elements preserved through centuries of retelling because they were part of the traditional material.

This doesn’t mean Homer’s account is historically accurate in detail. The gods didn’t actually intervene in battles. Achilles probably wasn’t invulnerable everywhere except his heel. The ten-year duration may be stylized. But the core event, a Greek coalition attacking and destroying a wealthy city at the entrance to the Black Sea, now appears to have actually happened.

Why Troy Mattered

Understanding why the Greeks might have attacked Troy requires understanding Bronze Age economics. Troy sat at the entrance to the Dardanelles, the strait connecting the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea. Any ship passing between these seas had to pass within sight of Troy’s walls. This gave Troy extraordinary power over trade routes linking the Mediterranean world to the grain, metals, and slaves of the Black Sea region.

The Mycenaean Greeks were aggressive traders and, when trade failed, aggressive raiders. Their palace economies depended on imported materials: tin for bronze, gold for prestige goods, grain for feeding palace workers. Any power controlling access to the Black Sea trade represented both an opportunity and a threat. An alliance with Troy meant guaranteed access; enmity meant the risk of being cut off from vital resources.

The archaeological record shows that Troy VIIa was wealthy and well-fortified, suggesting it was either directly controlling passage through the straits or benefiting enormously from doing so. The Greeks had both motive and means to attack. Whether the trigger was an abducted queen named Helen or a trade dispute gone sour, the underlying geopolitical tension was real.

The destruction of Troy VIIa coincides with the broader Bronze Age collapse, a period when civilizations across the Eastern Mediterranean fell in rapid succession. The Mycenaean palaces themselves were destroyed within a generation of Troy’s fall. Egypt barely survived invasion by mysterious “Sea Peoples.” The Hittite Empire vanished entirely. Whatever happened at Troy was part of this larger catastrophe, perhaps an early symptom of the instability that would eventually consume the Greeks themselves.

The Bigger Picture

The new evidence from Troy matters beyond settling an ancient debate. It raises questions about how we evaluate the historical content of mythological traditions. For centuries, educated opinion held that Homer’s epics were pure fiction, that treating them as historical sources was naive at best. The archaeological record increasingly suggests this dismissal was premature.

This doesn’t mean we should accept ancient traditions uncritically. The Iliad contains obvious mythological elements that cannot be literally true. But it suggests that ancient people were better at preserving historical information than modern skeptics assumed. Oral traditions, dismissed as unreliable, may carry kernels of authentic memory across centuries.

The implications extend beyond Homeric studies. Other ancient traditions, from the Hebrew Bible to Norse sagas to indigenous oral histories, may contain more historical content than currently recognized. The archaeological confirmation of the Trojan War provides a model for how to investigate these traditions: not by accepting them wholesale, but by identifying the testable claims they make and checking those claims against physical evidence.

The sling stones of Troy tell a story that Homer also told, in different form, three millennia ago. The convergence of archaeological evidence and literary tradition suggests that underneath the mythology, underneath the divine interventions and heroic exaggerations, something real happened on that windy plain overlooking the Dardanelles. The Greeks came to Troy. They fought. They won. And someone remembered.

Sources: Archaeology Magazine January/February 2026, Turkish archaeological ministry reports on Troy excavations, History Channel 2025 archaeological discoveries, Bronze Age Aegean scholarship, Homeric studies on oral tradition preservation.