In the dense jungles of modern-day Belize, beneath the ruins of what was once one of the largest Maya cities in the world, archaeologists have opened a tomb that has remained sealed for approximately 1,700 years. Inside they found a jade death mask made from dozens of individually carved pieces, carved bones bearing the names of gods, rare Spondylus shells from the distant Pacific Ocean, and the remains of a man who changed history.

His name was Te K’ab Chaak, which translates roughly to “Tree Branch Rain God.” According to Maya inscriptions, he was the founder of the Caracol dynasty, the first in a line of kings who would rule for centuries. The discovery of his tomb confirms what historians suspected from textual evidence: that Caracol had a founding moment, a specific king who established its royal line, and that the Maya remembered and revered that founding across generations.

The artifacts recovered tell us about more than one man. They reveal the Maya’s connections to distant regions, their beliefs about kingship and the afterlife, and their extraordinary skill in working jade, the most precious material in the Mesoamerican world. Te K’ab Chaak was buried to ensure he would rule in death as he had in life, and the care taken with his burial reflects his significance to those who followed him.

Who Was Te K’ab Chaak?

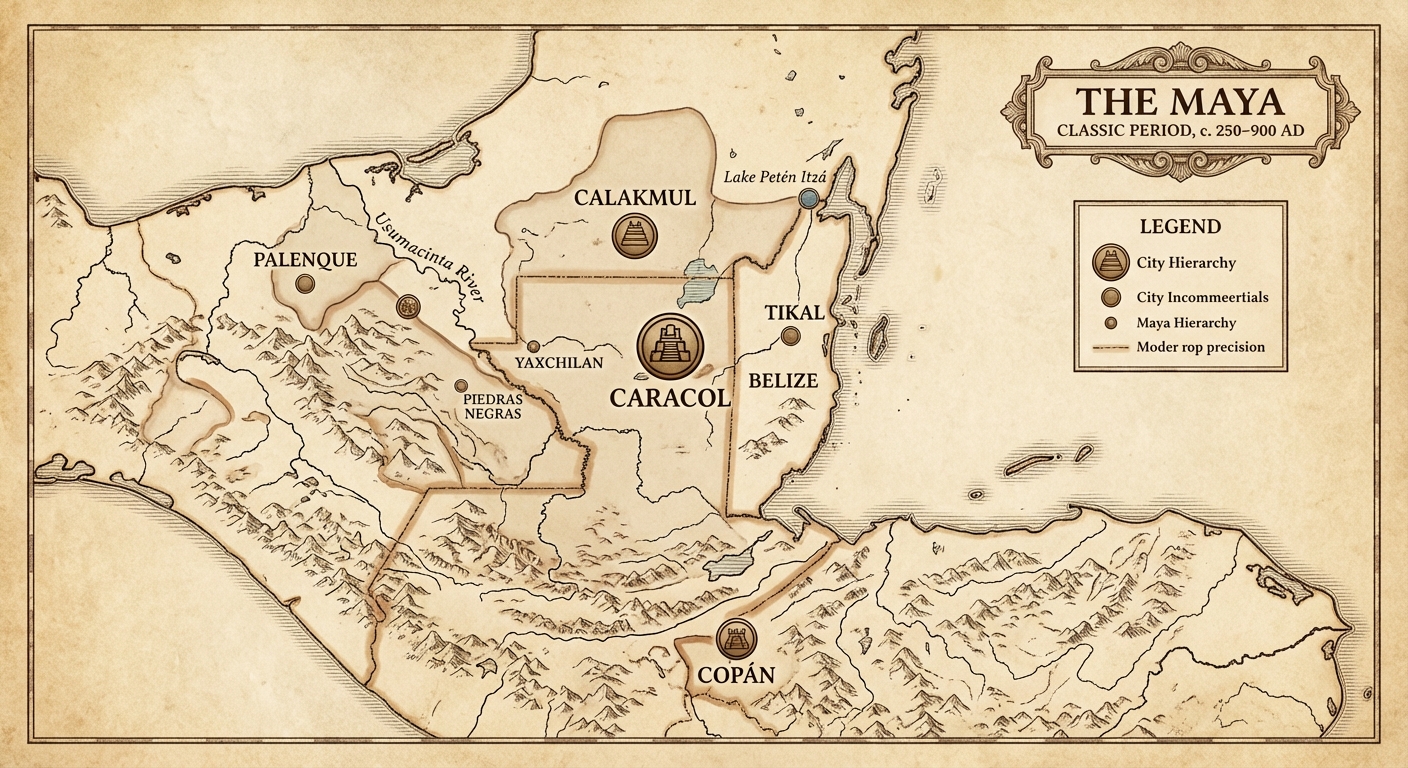

Caracol, known to the ancient Maya as Oxwitza’ (translated as “Three Hills Water”), was one of the major powers of the Classic Maya period (roughly 250-900 CE). At its height, the city covered over 65 square miles and may have housed over 100,000 people. Its kings waged war against rival cities, erected monumental buildings, and recorded their histories on carved stone monuments called stelae.

The earliest stelae at Caracol date to the late fourth century CE, but they reference earlier rulers. Te K’ab Chaak appears in these texts as the dynastic founder, the king from whom all subsequent rulers derived their legitimacy. His reign is estimated to have begun around 331 CE, though dating Maya events precisely is often challenging. He ruled during a period when Caracol was rising from a regional center to a major power.

Before the tomb discovery, Te K’ab Chaak was known only from inscriptions. No physical evidence of his existence had been found. His tomb changes this, providing material confirmation of a figure known from texts. This kind of correlation between textual and archaeological evidence is rare and valuable, allowing historians to connect written history with the physical reality of the past.

The location of the tomb, beneath a later temple complex, suggests that Caracol’s subsequent rulers deliberately built over their founder’s resting place. This practice, common among the Maya, served to connect living kings with ancestral authority. By building temples above royal tombs, later rulers could perform rituals that invoked their ancestors’ power. Te K’ab Chaak, in death, literally supported the structures of those who claimed descent from him.

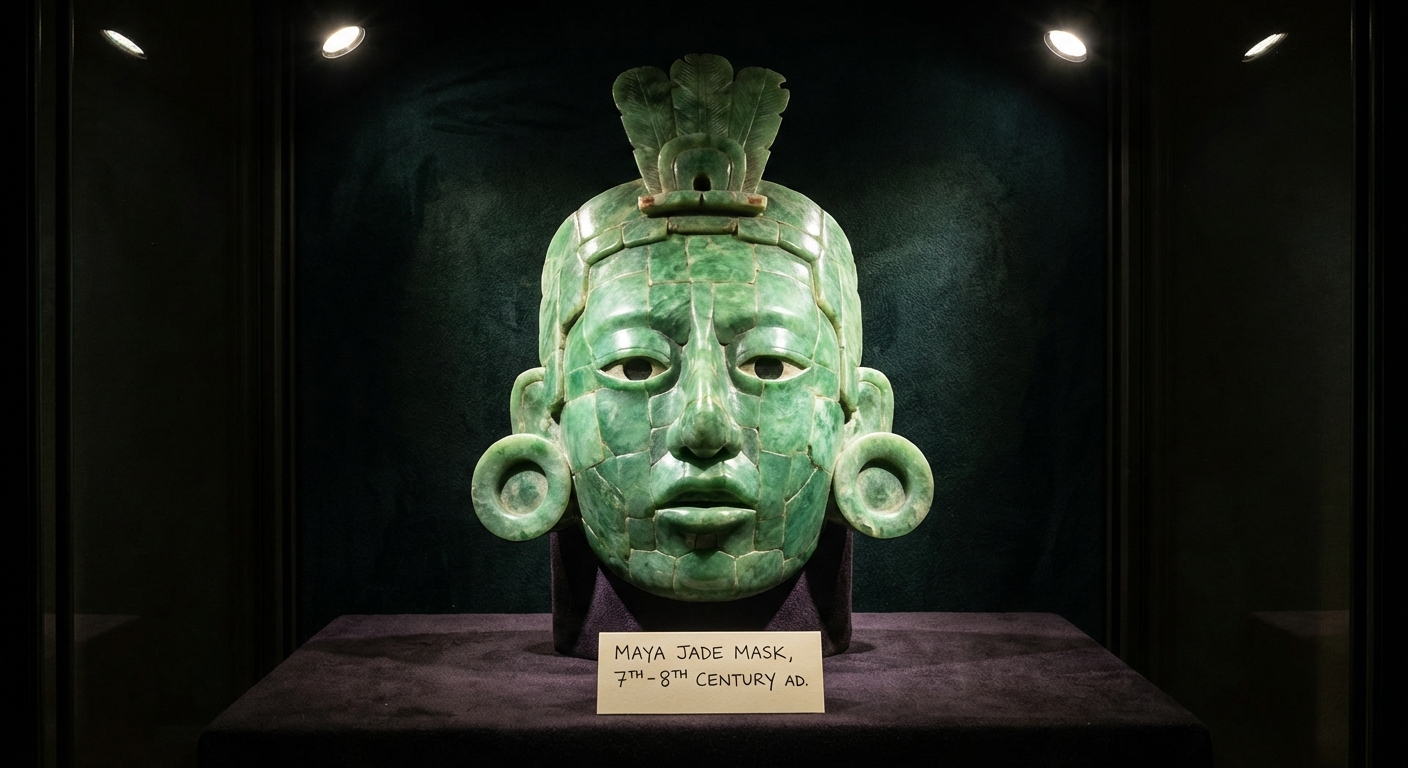

The Jade Death Mask

The most spectacular artifact from the tomb is the jade death mask, assembled from over 40 individual pieces of worked jade. Each piece was carefully shaped and polished, then fitted together to create a portrait that covered the face of the deceased king. The mask shows a serene expression, with wide eyes, broad nose, and slightly parted lips characteristic of Maya elite portraiture.

Jade held profound significance in Maya culture. It represented life, breath, water, and royal power. Its green color connected it to growing maize, the crop that sustained Maya civilization and featured in creation myths. Jade was harder than the materials available to Maya craftspeople, making it extraordinarily difficult to work. A mask of this complexity represents months of skilled labor.

The mask’s style places it firmly in the Early Classic period, consistent with the textual date for Te K’ab Chaak’s reign. Stylistic analysis suggests influences from both local Belizean traditions and the great metropolis of Teotihuacan in central Mexico, which dominated Mesoamerican politics during this era. The king’s burial demonstrates Caracol’s connections to the wider Mesoamerican world even at this early date.

Jade masks are known from other Maya royal tombs, most famously from Palenque’s Temple of the Inscriptions, where the great king K’inich Janaab Pakal was buried with an elaborate jade mask in 683 CE. Te K’ab Chaak’s mask is earlier and from a different region, expanding our understanding of when and where this practice occurred. It suggests that jade masks were a widespread feature of Maya royal burial from early in the Classic period.

The Grave Goods and Their Meaning

Beyond the mask, the tomb contained an array of objects chosen to equip the dead king for eternity. Carved bones bear hieroglyphic texts naming gods and recording ritual actions. These may have been used in divination ceremonies during the king’s life, then buried with him to continue their function in the afterlife. Maya kings were intermediaries between humans and gods; their burial goods maintained this role beyond death.

The Spondylus shells are particularly significant. These marine mollusks come from the Pacific coast, hundreds of miles from Caracol. Their presence in a tomb in the highlands of Belize demonstrates long-distance trade networks connecting the Maya lowlands to coastal regions. Spondylus shells were highly valued throughout the Americas, appearing in elite contexts from Peru to the American Southwest. Their inclusion marks Te K’ab Chaak as a participant in continent-spanning exchange systems.

Pottery vessels found in the tomb would have contained offerings of food and drink for the deceased. Chemical analysis of residues inside these vessels may eventually reveal what specific substances were included. Maya royal tombs from other sites have yielded evidence of chocolate, maize gruel, and psychoactive substances. The dead were expected to feast in the afterlife, and their tombs were provisioned accordingly.

The arrangement of objects within the tomb also carries meaning. Maya burials often positioned bodies and grave goods in symbolically significant orientations. The cardinal directions, the layers of the Maya cosmos (sky, earth, underworld), and the movements of celestial bodies all influenced burial practices. Detailed analysis of how Te K’ab Chaak’s remains and offerings were positioned will yield insights into the cosmological beliefs of early Caracol.

Caracol After Te K’ab Chaak

The dynasty Te K’ab Chaak founded would rule Caracol for over three centuries. His successors expanded the city, waged wars against rival powers, and erected the monuments that allow historians to reconstruct their reigns. The dynasty’s greatest triumph came in 562 CE, when Caracol defeated the mighty Tikal, inaugurating a period of regional dominance.

Understanding the dynasty’s founder helps explain its later trajectory. The elaborate burial given to Te K’ab Chaak suggests that dynastic legitimacy was important from the start. Later kings who invoked their descent from this founder were drawing on a tradition of reverence that the burial itself helped establish. The tomb was not just a resting place but a political statement, anchoring the dynasty in sacred antiquity.

The Maya practice of building over ancestral tombs meant that Te K’ab Chaak’s resting place became increasingly central to Caracol’s sacred geography. Each new temple built above added layers of meaning and power. Rituals performed at the surface connected with the founder below, channeling ancestral authority into current political action. The dead king remained active in the affairs of the living.

Caracol eventually declined along with other Maya polities during the Terminal Classic period (800-1000 CE). The city was gradually abandoned, its temples consumed by jungle growth. The tomb of Te K’ab Chaak remained sealed beneath the roots and soil, waiting for archaeologists to rediscover what the jungle had hidden.

The Bigger Picture

The discovery of Te K’ab Chaak’s tomb contributes to a broader effort to understand Maya political organization. For decades, Maya studies focused on inscriptions, art, and architecture. But archaeological excavation of royal tombs provides different kinds of information: the actual bodies of rulers, the physical objects they valued, the rituals performed at their burial.

This tomb is particularly valuable because it dates to the Early Classic period, when many Maya institutions were still forming. Later tombs are more numerous but represent a mature civilization. Te K’ab Chaak lived during the period when that civilization was being defined, when practices that would persist for centuries were first being established. His burial shows us what early Maya kingship looked like, before later elaborations.

The discovery also highlights ongoing archaeological work in Belize, a country with extraordinary Maya heritage but limited resources for excavation. International collaboration, combining Belizean expertise with outside funding and technology, has enabled discoveries that neither party could accomplish alone. The study of the ancient Maya benefits from this cooperation, revealing more of a civilization that flourished for over two millennia.

Te K’ab Chaak has been dead for 17 centuries. But the opening of his tomb brings him back into history, transforming him from a name in inscriptions to a physical presence whose remains and possessions can be studied. The jade mask, the carved bones, the shells from distant oceans, all these speak to who he was, what he valued, and how his successors chose to remember him. The Tree Branch Rain God has returned.

Sources: Archaeology Magazine January/February 2026, Belize Institute of Archaeology announcements, Maya archaeology scholarship on Classic period royal tombs, Caracol Archaeological Project publications.