The Valley of the Kings has been excavated continuously for over two centuries. Howard Carter found Tutankhamun’s tomb there in 1922, the last pharaonic burial discovered in the valley. Since then, archaeologists have mapped every square meter, used ground-penetrating radar, employed thermal scanning, and generally assumed that any major discovery would require looking elsewhere. The valley, by consensus, was exhausted.

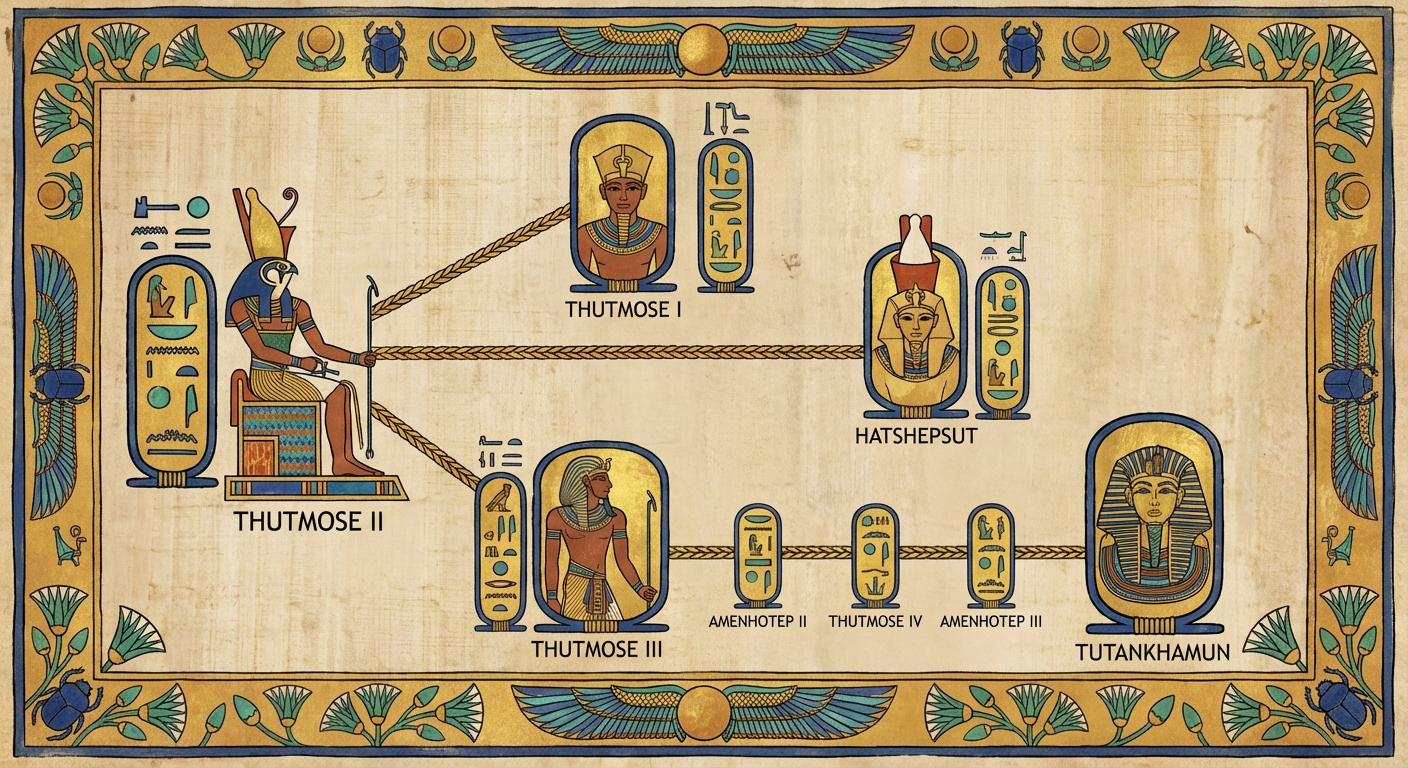

That consensus was wrong. In late 2025, Egyptian archaeologists announced the discovery of the tomb of Thutmose II, a pharaoh who ruled approximately 3,500 years ago. The find is the first pharaonic tomb discovered at the Valley of the Kings in over a century. Thutmose II was the great-great-great-great-great grandfather of Tutankhamun, connecting this discovery directly to the most famous archaeological find in history.

The discovery raises immediate questions: How did a pharaoh’s tomb remain hidden for so long? What does this reveal about what we still don’t know? And what might it contain? The answers illuminate both ancient Egyptian burial practices and the ongoing capacity for archaeological sites to surprise us.

Who Was Thutmose II?

Thutmose II ruled Egypt during the Eighteenth Dynasty, approximately 1493-1479 BCE. His reign was relatively brief, perhaps only three years, and his health appears to have been poor. Examinations of his mummy, discovered elsewhere in a cache of relocated royal mummies, revealed a man who died young with skin lesions possibly indicating disease.

His place in history is largely defined by the women around him. His father was Thutmose I, a military pharaoh who expanded Egypt’s borders. His half-sister and wife was Hatshepsut, who would become one of ancient Egypt’s most powerful rulers after Thutmose II’s death. His son, Thutmose III, became perhaps the greatest military pharaoh of all, the “Napoleon of Egypt.”

Thutmose II’s tomb had never been definitively located. His mummy was found in the Deir el-Bahri cache, a hiding place where priests of later dynasties relocated royal mummies to protect them from tomb robbers. This relocation meant his original burial site remained unknown. Various candidates were proposed over the years, but none was confirmed until now.

The discovery fills a significant gap in our knowledge of New Kingdom burial practices. We knew Thutmose II existed, knew his mummy, knew his position in the royal succession. What we didn’t know was where he intended to spend eternity. That question has now been answered.

How They Found It

Modern archaeology uses technology that would have seemed magical to earlier generations. Ground-penetrating radar sends electromagnetic pulses into the earth and reads their reflections, revealing buried structures. Thermal imaging detects temperature differences that indicate cavities or different materials underground. LiDAR creates precise three-dimensional maps of terrain. Together, these tools can reveal what lies beneath without digging.

But technology doesn’t work alone. The Valley of the Kings has been scanned repeatedly with every available method. The tomb remained hidden not because scanning failed but because interpreting scan results requires human expertise and, sometimes, luck. A junior team member noticed an anomaly in radar data that had been previously dismissed as natural rock formation. Follow-up investigation proved it was anything but natural.

The entrance was concealed beneath debris from later construction. Ancient Egyptian workers building nearby tombs had unknowingly buried the entrance under rock chips and excavation waste. Over three millennia, this debris layer hardened and became indistinguishable from natural geology. The tomb wasn’t discovered earlier because, in a very real sense, it had ceased to exist as a visible feature of the landscape.

Excavation began carefully. Egyptian archaeological protocol now emphasizes meticulous documentation over rapid exploration. Every layer of debris was photographed, sampled, and recorded before removal. The process took months, but it preserved information that faster methods would have destroyed. By the time excavators reached the tomb entrance, they understood not just where it was but how it had become hidden.

What the Tomb Contains

Full details of the tomb’s contents remain unpublished, but preliminary reports indicate it survived in better condition than most Valley of the Kings burials. The rock-cut chambers retain painted wall decorations depicting standard funerary scenes: the deceased pharaoh meeting gods, traveling through the underworld, achieving immortality. The artistic style is consistent with early Eighteenth Dynasty work, confirming the attribution to Thutmose II’s period.

The tomb shows evidence of ancient disturbance. This was expected; tomb robbery was endemic in ancient Egypt, and most royal burials were looted within centuries of their creation. The question is how much disturbance occurred and when. Some tombs were emptied completely; others retained significant contents despite robbery. Early indications suggest this tomb falls somewhere in between.

Specific artifacts mentioned in preliminary reports include pottery vessels, fragments of funerary furniture, and what appears to be portions of a wooden shrine. The sarcophagus chamber is reported intact but the sarcophagus itself empty, consistent with the mummy having been removed in antiquity. What this means for the tomb’s original contents remains to be determined through careful study.

The absence of Thutmose II’s mummy from his tomb is actually useful information. We know his mummy was moved to the Deir el-Bahri cache, presumably during the Twenty-First Dynasty when priests systematically relocated royal burials. Finding the original tomb helps us understand the logistics of this operation: where the mummy came from, what route the priests might have taken, what they left behind.

What This Means for Egyptology

The discovery challenges assumptions that had hardened into certainty. The Valley of the Kings was considered archaeologically exhausted, a site where only minor discoveries remained possible. Finding a pharaoh’s tomb there demonstrates that even intensively studied sites can harbor significant secrets.

This has implications beyond Egypt. Archaeological sites worldwide have been declared “fully excavated” or “completely documented.” The Valley of the Kings discovery suggests these declarations may be premature. New technologies, new perspectives, and sometimes just fresh eyes can reveal what previous generations missed.

The timing is also significant. Egyptian archaeology has faced criticism for being dominated by foreign expeditions that prioritized spectacular finds over systematic study. Recent decades have seen a shift toward Egyptian-led research focusing on understanding context rather than extracting objects. The Thutmose II discovery emerged from this approach: Egyptian archaeologists, working methodically, made the find that a century of foreign excavation missed.

The find also renews questions about what else might be hidden. At least two pharaohs from the Eighteenth Dynasty lack confirmed tombs: Thutmose II has now been found, but others remain missing. Speculation has long centered on the possibility of hidden chambers within known tombs, including Tutankhamun’s. The discovery of a completely unknown tomb makes such speculation seem less fanciful.

The Bigger Picture

Archaeological discovery often follows a pattern: initial exploration finds the obvious sites, then decades of refinement map and study them, then the site is declared exhausted, then something unexpected appears. The Valley of the Kings has now completed this cycle, proving that “exhausted” is often a premature verdict.

The Thutmose II discovery connects to broader questions about what we know and what we think we know. Every generation believes it has largely figured out the past, that only details remain to be filled in. Every generation is wrong. The physical remains of human history are incompletely mapped, incompletely excavated, incompletely understood. The Valley of the Kings is one of the most studied archaeological sites on Earth, and it still harbored a pharaoh’s tomb that no one knew existed.

For the study of ancient Egypt specifically, this discovery reminds us how much the accident of survival shapes our knowledge. We know enormously more about Tutankhamun, a minor pharaoh who died young, than about Thutmose III, one of Egypt’s greatest rulers, simply because Tutankhamun’s tomb survived intact while Thutmose III’s was thoroughly looted. Each new discovery shifts this imbalance slightly, adding data points that help us see past the distortions of chance preservation.

The tomb of Thutmose II is still being studied. Months or years of careful work remain before full publication. But the fact of its existence has already changed what we thought we knew about a site that has been excavated for over two hundred years. Somewhere beneath the sands, other secrets wait.

Sources: Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announcements, Archaeology Magazine January/February 2026, History Channel archaeological discoveries 2025, Zahi Hawass statements on Valley of the Kings research, Egyptological scholarship on Eighteenth Dynasty royal burials.