Every year, the ocean absorbs roughly 25 percent of the carbon dioxide humans emit. Without this service, atmospheric CO2 levels would be dramatically higher, and climate change would be accelerating even faster than it already is. The ocean is Earth’s largest carbon sink, a planetary-scale climate defense system that operates silently beneath the waves.

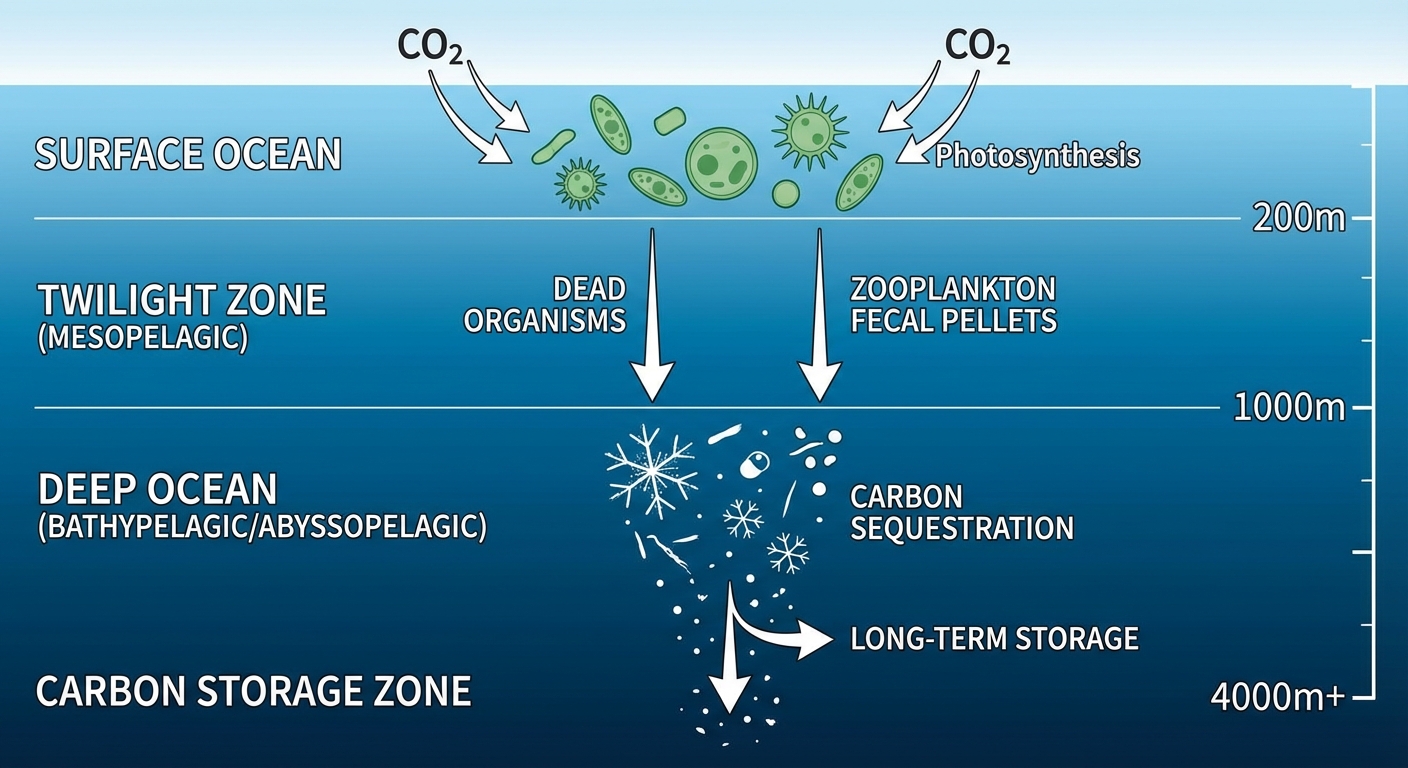

This system depends on living things. Phytoplankton at the ocean surface absorb CO2 through photosynthesis, just like plants on land. When these organisms die, they sink toward the ocean floor, carrying their carbon with them. This “biological pump” has been pulling carbon from the atmosphere and sequestering it in the deep ocean for hundreds of millions of years.

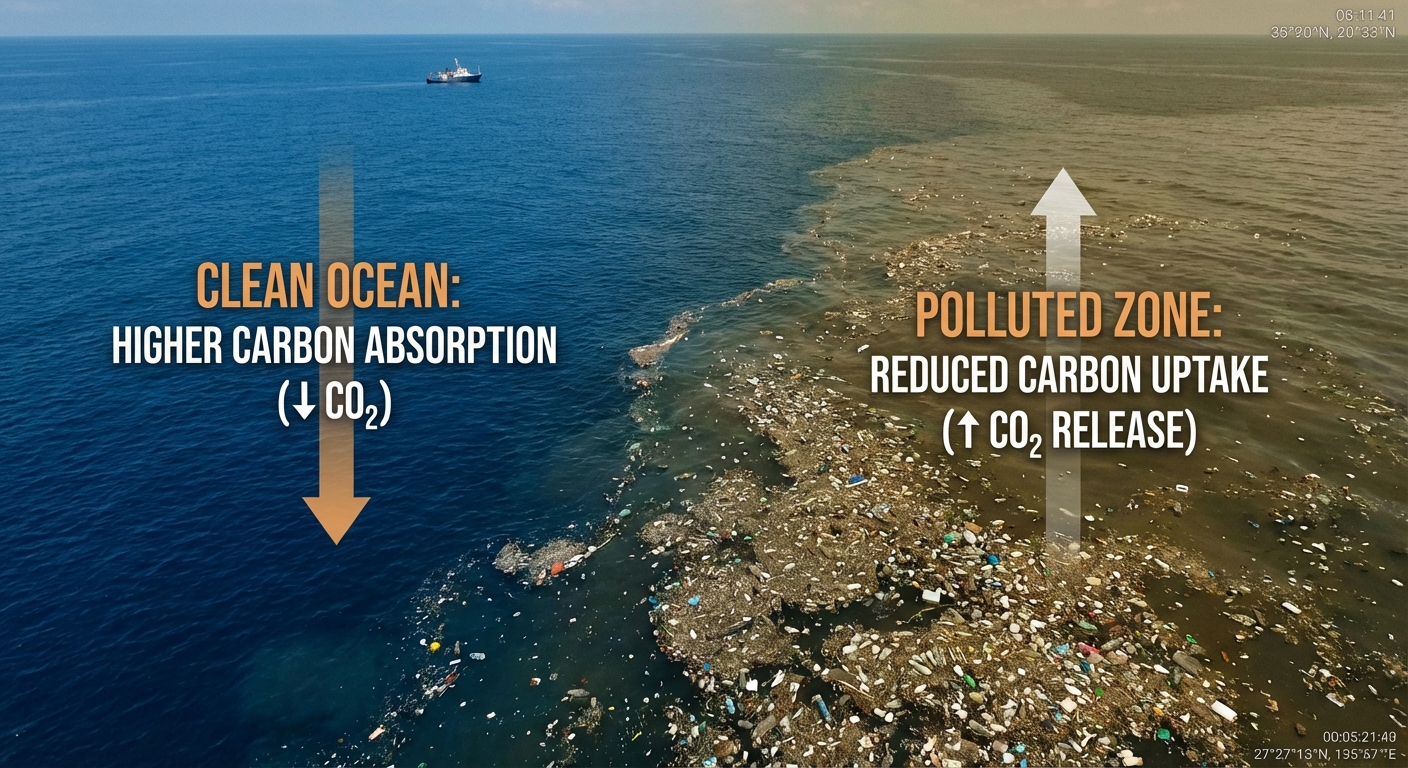

New research suggests microplastics may be disrupting this process. Tiny plastic particles, drifting through the oceans in quantities that beggar imagination, appear to be interfering with the marine organisms that drive the biological pump. If confirmed, this means plastic pollution isn’t just harming individual animals; it’s potentially weakening one of Earth’s most important climate defense mechanisms.

The Biological Pump Explained

The ocean’s carbon cycle is more complex than the terrestrial one. On land, carbon moves between atmosphere, plants, and soil in relatively straightforward ways. In the ocean, carbon takes multiple pathways, some physical, some chemical, some biological. The biological pump is the most important of these pathways for removing carbon from surface waters where it can exchange with the atmosphere.

Phytoplankton are the key players. These microscopic photosynthetic organisms float near the ocean surface, using sunlight to convert CO2 and water into organic matter. They’re responsible for roughly half of all photosynthesis on Earth, making them as important for oxygen production and carbon capture as all terrestrial plants combined.

When phytoplankton die, they begin sinking. On their own, individual cells sink slowly and tend to decompose before reaching the deep ocean, releasing their carbon back into the water. But several processes speed this transport. Zooplankton (tiny animals) eat phytoplankton and excrete fecal pellets that sink much faster than individual cells. Phytoplankton also clump together into aggregates called “marine snow,” which sink rapidly.

The faster material sinks, the more likely it is to reach the deep ocean before decomposing. Once carbon reaches depths below the thermocline (the boundary between warm surface waters and cold deep waters), it’s effectively removed from contact with the atmosphere for centuries to millennia. The biological pump is thus a race between sinking and decomposition, and anything that slows sinking or speeds decomposition weakens the pump.

How Microplastics Enter the Picture

Microplastics are plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters, though most are much smaller, some microscopic. They come from multiple sources: larger plastics breaking down in the environment, synthetic fibers released during laundry, microbeads from personal care products, and direct industrial emissions. By some estimates, there are now more microplastic particles in the ocean than stars in the Milky Way.

These particles don’t just drift passively. They interact with marine organisms in multiple ways. Zooplankton, which can’t distinguish microplastics from food, ingest them. Phytoplankton may become coated with plastic particles or have their growth affected by chemicals leaching from nearby plastics. Even bacteria, the organisms responsible for decomposing organic matter, may behave differently in the presence of microplastics.

The new research documents several mechanisms by which microplastics could weaken the biological pump. First, zooplankton that consume microplastics instead of phytoplankton contribute less to carbon transport. Their fecal pellets contain less organic carbon and more inert plastic. Since fecal pellets are major drivers of carbon transport, this represents a direct reduction in pump efficiency.

Second, microplastics may alter the buoyancy of sinking organic matter. Plastics are generally less dense than seawater and tend to float. When incorporated into marine snow or fecal pellets, they could slow sinking rates, giving decomposers more time to release carbon before it reaches the deep ocean.

The Research Findings

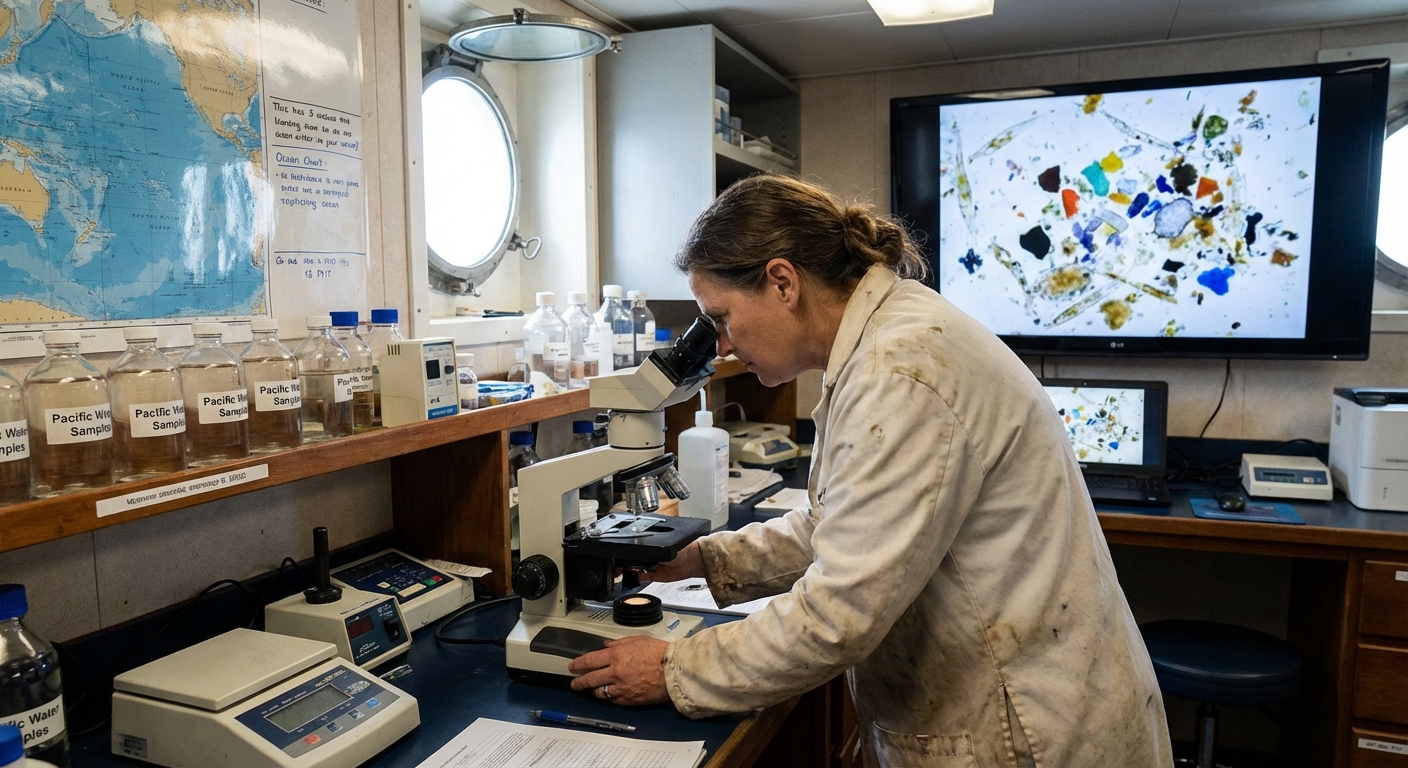

Multiple studies have contributed to the emerging picture of microplastics affecting carbon cycling. Laboratory experiments have shown that zooplankton exposed to microplastics produce fecal pellets with lower carbon content and altered sinking characteristics. Field observations have found microplastics incorporated into marine snow at various ocean locations. Modeling studies have attempted to estimate the overall impact on carbon flux.

The most concerning findings relate to fecal pellet transport. Zooplankton fecal pellets are responsible for a disproportionate share of carbon transport to the deep ocean because they sink so quickly. Research has shown that microplastic-laden pellets sink up to 25 percent slower than clean pellets in laboratory conditions. Over the thousands of meters these pellets must travel, reduced sinking speed means significantly more decomposition and carbon release before reaching the deep ocean.

The spatial distribution of the effect matters. Microplastics are concentrated in certain ocean regions, particularly the centers of major gyres (the large circular current systems in each ocean basin). These “garbage patches” are also regions where the biological pump operates, meaning the heaviest microplastic pollution coincides with important carbon cycling areas.

Quantifying the total impact remains challenging. The ocean is vast, microplastics are unevenly distributed, and the biological pump varies by region and season. Current estimates suggest that microplastics could be reducing biological pump efficiency by a few percent globally, with higher impacts in heavily polluted areas. A few percent might seem small, but given the scale of oceanic carbon absorption, it translates to millions of tons of CO2 that might otherwise have been sequestered.

Implications for Climate

The ocean’s carbon absorption has been partially masking the full impact of human emissions. If this absorption weakens, atmospheric CO2 will rise faster for any given level of emissions. We would need to reduce emissions even more aggressively to achieve the same climate outcomes.

This creates a feedback loop. More plastic pollution means less efficient carbon absorption, which means faster climate change, which stresses marine ecosystems further, potentially reducing their capacity to absorb carbon through additional mechanisms. The system could enter a declining spiral where pollution and climate change reinforce each other.

The research also highlights an underappreciated connection between environmental problems. Plastic pollution and climate change are often discussed as separate issues, requiring separate solutions. But if plastics are weakening the ocean’s climate defense, these problems are linked. Addressing plastic pollution becomes, in part, a climate mitigation strategy. Failing to address it makes climate targets harder to reach.

This doesn’t mean we should abandon efforts to reduce emissions and focus instead on plastic pollution. The scale of emissions reduction needed for climate stability dwarfs any impact from improved carbon absorption. But it does mean that plastic pollution has consequences beyond the visible harms to marine wildlife. The invisible effects on ocean biogeochemistry may ultimately be more significant.

The Bigger Picture

The microplastics-carbon research illustrates how human activities create unexpected connections in Earth’s systems. Plastic was developed for convenience and durability, qualities that make it so persistent in the environment. The same properties that make plastic useful make it a long-term pollutant. And that pollution, we’re now learning, doesn’t just harm individual organisms but potentially alters planetary-scale processes.

The ocean has been absorbing carbon and buffering climate change without our awareness or appreciation. We only recognize this service when we threaten it. The research on microplastics is, in this sense, a warning about taking ecosystem services for granted. The processes that make Earth habitable are complex, interconnected, and vulnerable to disruption from multiple directions.

Marine scientists often describe the ocean as “out of sight, out of mind.” Most human attention focuses on the thin film of land surface where we live. But most of Earth’s surface is ocean, and most of the biosphere’s carbon cycling happens there. Understanding how our activities affect these processes is essential for managing our planetary impact.

The tiny plastic particles drifting through the ocean are now interacting with the tiny organisms that drive global carbon cycles. Neither is visible to the unaided eye, yet their interaction may influence the climate that all of us experience. The microscopic and the planetary are connected in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Sources: ScienceDaily ocean and climate research 2026, marine biology carbon pump studies, microplastics in marine ecosystems research reviews, NOAA ocean carbon monitoring data.