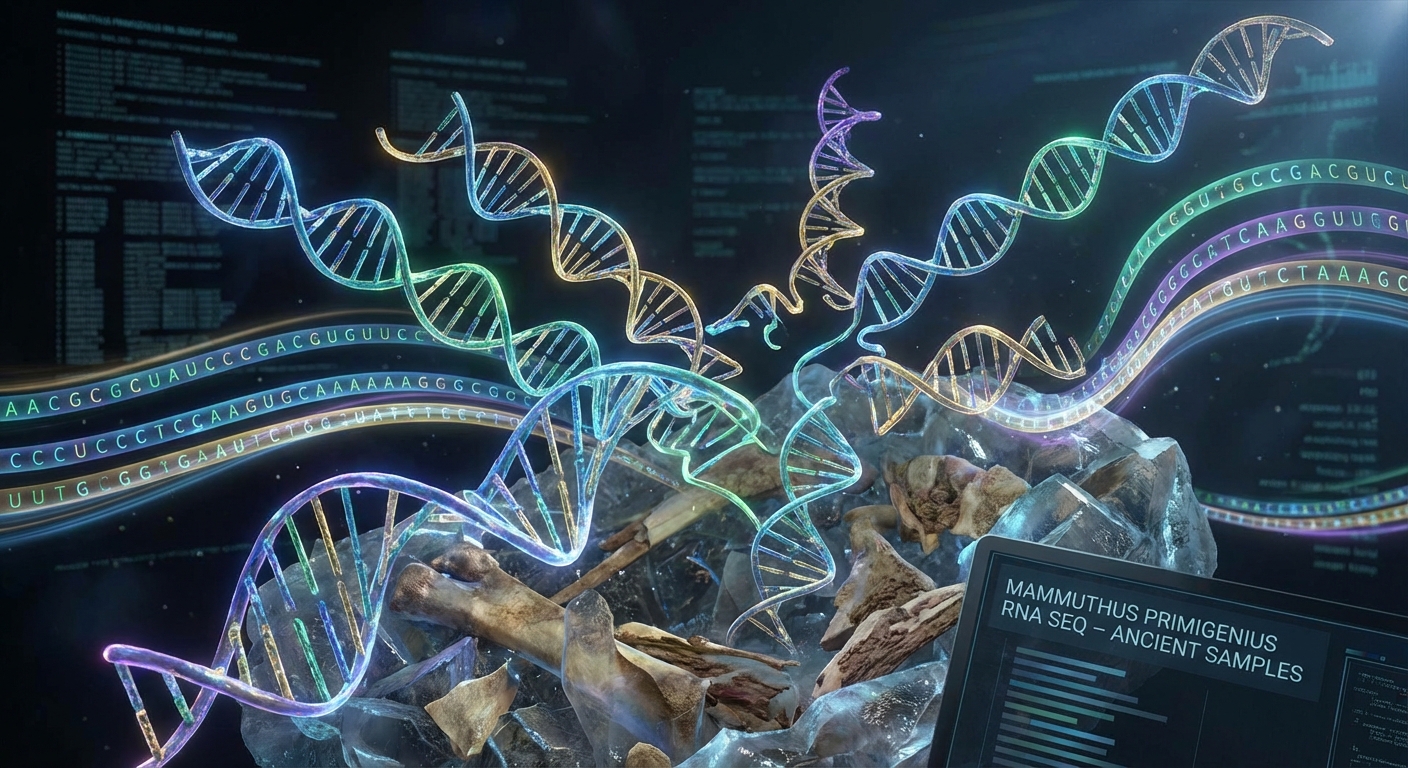

The woolly mammoth died roughly 40,000 years ago, when glaciers covered much of the Northern Hemisphere and our own species was just beginning to spread beyond Africa. Its body sank into Siberian permafrost and remained there through the rise and fall of civilizations, through ice ages and warm periods, through everything that would become human history. Then, in 2025, scientists announced they had done something previously thought impossible: they had recovered and sequenced its RNA.

The achievement, published in the journal Cell, represents a fundamental breakthrough in our ability to understand extinct life. DNA tells us what genes an organism carried, the genetic blueprint from which its body was built. RNA tells us which of those genes were actually active, what the creature was doing at the cellular level in the moments before death. For the first time, we can see not just what a mammoth was but how it lived.

Why RNA Matters

To understand why this discovery is so significant, you need to understand the difference between DNA and RNA. DNA is the stable master copy of genetic information, locked away in the nucleus of every cell. It contains all the genes an organism possesses but does not directly control what the organism does at any given moment. That role belongs to RNA.

RNA is the working copy, transcribed from DNA when the cell needs to produce a protein. Different cells in the same organism express different genes: a liver cell produces liver proteins, a brain cell produces brain proteins, even though both contain identical DNA. By examining which RNA molecules are present in a tissue sample, scientists can determine which genes were active at the time of death.

This information has been available for living organisms and recently deceased specimens for decades. But RNA was thought to degrade quickly after death, breaking down into fragments within hours or days. The idea that RNA could survive for tens of thousands of years seemed like fantasy. The Siberian mammoth proved otherwise.

The Discovery

Researchers from Stockholm University and the Swedish Museum of Natural History made the breakthrough while studying a juvenile woolly mammoth specimen that had been preserved in Siberian permafrost. The animal, estimated to have died around 40,000 years ago, was remarkably well preserved, with soft tissue, skin, and even hair remaining intact.

The key was the permafrost itself. Frozen conditions slow chemical reactions to a near standstill, and the mammoth had remained frozen without interruption since the Pleistocene. When the researchers carefully extracted tissue samples and analyzed them using cutting-edge sequencing techniques, they found intact RNA molecules, degraded but still readable.

The team sequenced RNA from multiple tissue types, including skin and muscle. They found tissue-specific expression patterns that matched what we would expect from living elephants, the mammoth’s closest living relatives. Skin samples showed genes associated with skin function. Muscle samples showed genes associated with muscle development and maintenance. The mammoth’s cellular machinery was frozen in action.

What the RNA Reveals

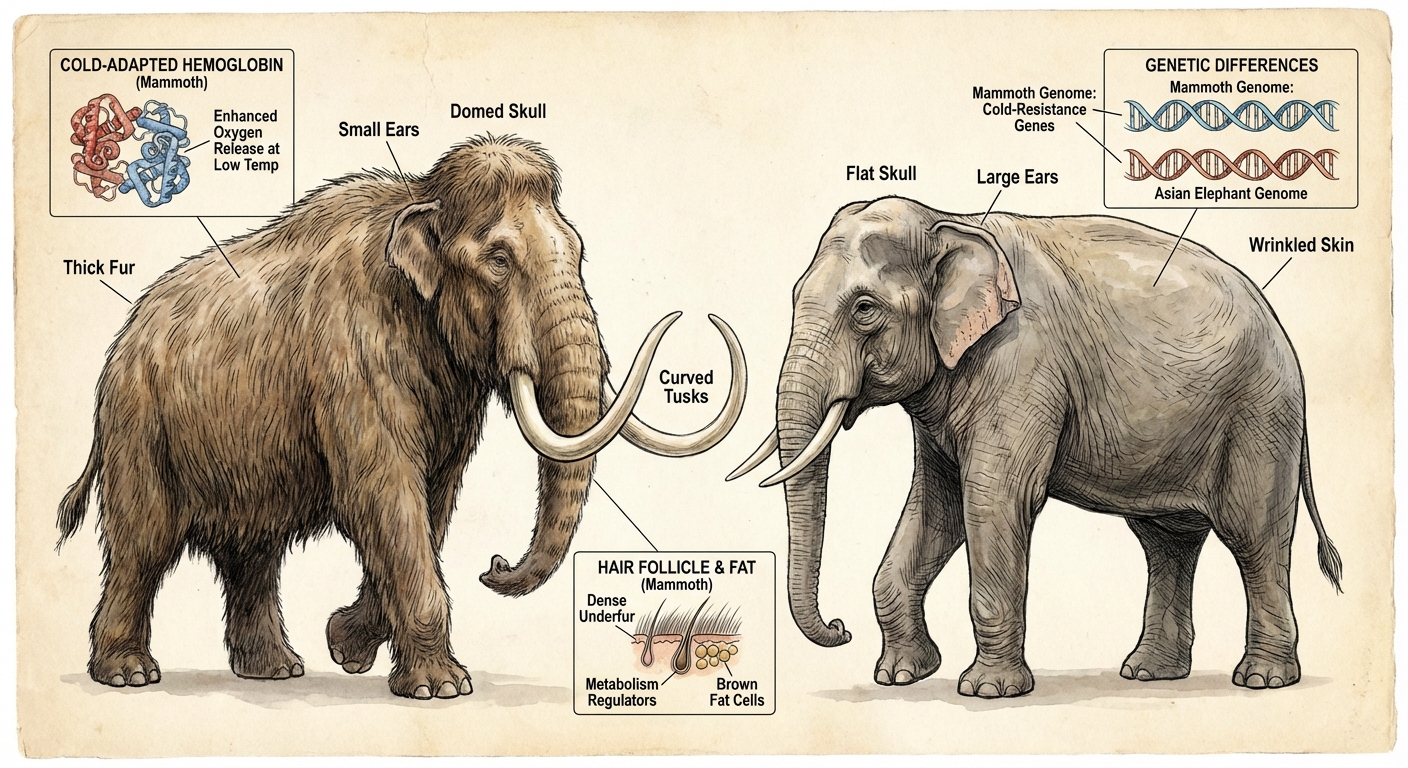

The RNA data provides insights that DNA alone could never offer. By examining which genes were active in the mammoth’s skin, for instance, researchers can understand the molecular basis of adaptations to cold environments. Woolly mammoths survived in conditions that would kill modern elephants. Their fur, their fat deposits, their circulatory systems all had to be optimized for extreme cold.

DNA studies had already identified some of the genes responsible for these adaptations, but DNA cannot tell us how strongly those genes were expressed or how they interacted with other genetic programs. The RNA data begins to fill in this picture, showing not just what genes the mammoth carried but how intensively those genes were being used.

This has direct implications for ongoing de-extinction projects. Several research teams are working to create mammoth-elephant hybrids by editing elephant genomes to include mammoth genes. But knowing which genes to add is only part of the challenge. Understanding how those genes should be regulated, how strongly they should be expressed, is equally important. The RNA data provides a template for this regulation.

Implications for De-Extinction

The mammoth de-extinction project has captured public imagination for years. The idea of restoring an iconic ice-age creature seems like science fiction made real. But the project has also faced significant scientific challenges. Even if researchers can insert mammoth genes into elephant cells, how do they ensure those genes function correctly?

Gene expression is not binary. Genes are not simply on or off but are expressed at different levels in different tissues at different times. A gene that should be highly active in skin cells might need to be suppressed in liver cells. Getting these patterns wrong could produce a creature that looks like a mammoth but lacks the physiological adaptations that allowed mammoths to thrive.

The RNA data offers a map of correct expression patterns. Researchers can now compare their hybrid cells to genuine mammoth tissue, checking whether the engineered genes are being expressed at appropriate levels. This does not solve all the challenges of de-extinction, but it removes one significant obstacle.

Broader Scientific Implications

Beyond mammoths, the discovery opens new possibilities for studying extinct species across the animal kingdom. If RNA can survive 40,000 years in permafrost, it may be recoverable from other frozen specimens. The Siberian permafrost has yielded remarkably preserved remains of cave lions, woolly rhinos, ancient horses, and other Pleistocene megafauna. Each of these specimens might contain RNA waiting to be sequenced.

The implications extend to human evolution as well. Neanderthals and other ancient humans lived in cold environments and some of their remains have been preserved in frozen or cold conditions. While no RNA has yet been recovered from ancient humans, the mammoth success suggests it may be possible. Imagine understanding not just which genes Neanderthals carried but which were active in their brains, their immune systems, their metabolisms.

Even beyond frozen specimens, the discovery suggests RNA may be more durable than previously believed. Scientists are now re-examining preservation conditions that might protect RNA in other environments. The boundaries of what can be known about ancient life are expanding.

The Bigger Picture

The recovery of 40,000-year-old RNA represents more than a technical achievement. It changes what we can know about the past. For most of history, our understanding of extinct creatures was limited to bones and teeth, the hard parts that fossilize. DNA added genetic information but still left gaps in our knowledge. RNA begins to fill those gaps, revealing not just what extinct animals were but what they were doing.

This matters because life is not static. An organism is not merely a collection of genes but a dynamic system in which genes are constantly being activated and suppressed, proteins produced and degraded, signals sent and received. To truly understand a mammoth, we need to understand it as a living system, not just a genetic code. RNA brings us closer to that understanding.

The mammoth that died 40,000 years ago could not know that one day its frozen remains would yield secrets invisible to the naked eye. It could not imagine the technologies that would read its molecular history or the scientists who would reconstruct its cellular activity. Yet there it lay, frozen in time, waiting for us to develop the tools to understand it. That we have finally done so feels like a small miracle, a message received across an almost unimaginable span of time.