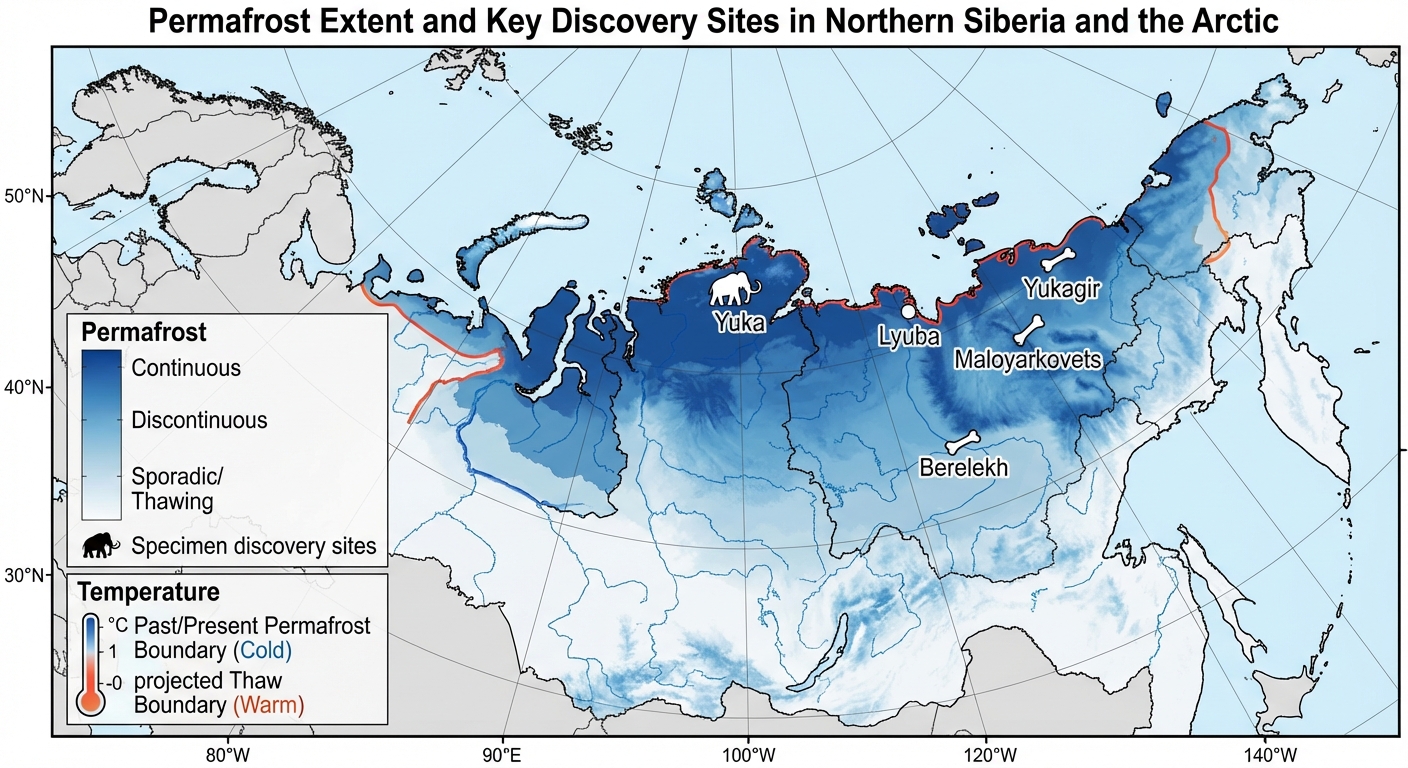

In 2010, hunters from the Yukaghir people discovered something remarkable frozen in the northern Siberian permafrost: the nearly intact body of a young woolly mammoth, its reddish-brown fur still clinging to preserved skin. They named her Yuka. Radiocarbon dating would place her death at roughly 40,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, when vast herds of mammoths roamed the frozen steppe. Yuka’s body was extraordinary enough as a specimen. What scientists extracted from it in 2025 would overturn fundamental assumptions about molecular preservation and open new windows into the lives of extinct species.

From Yuka’s preserved tissue, researchers at Stockholm University isolated and sequenced RNA molecules, the molecular messengers that translate genetic code into biological action. These sequences are the oldest RNA ever recovered, by a significant margin. Where DNA tells us what genes an organism had, RNA reveals which genes were actually active. “This is a snapshot of the last minutes or hours of Yuka’s life,” said University of Copenhagen genomicist Emilio Mármol-Sánchez, lead author of the study published in Cell. For the first time, we can see not just what a mammoth was but what it was doing at a molecular level in its final moments.

Why RNA Matters

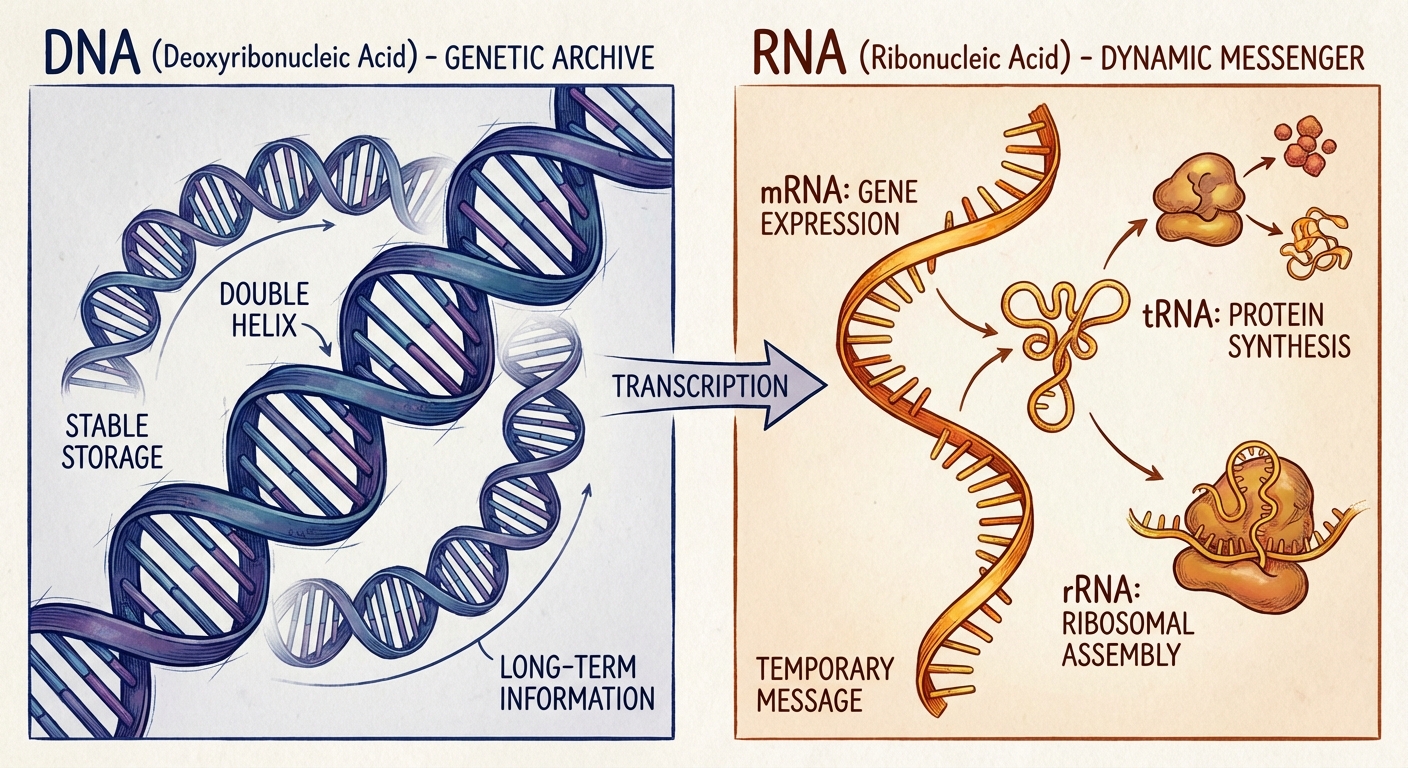

To understand why this discovery is revolutionary, you need to understand the difference between DNA and RNA. DNA is the blueprint, the instruction manual containing all the genes an organism inherits. Every cell in your body contains essentially the same DNA. But cells are spectacularly different: heart cells pump, nerve cells transmit signals, skin cells form barriers. The difference isn’t in the genes themselves but in which genes are turned on and off, expressed or silenced, active or dormant.

RNA is the evidence of that activity. When a gene is “expressed,” the cell transcribes its DNA sequence into messenger RNA, which then guides the production of proteins. By analyzing RNA, scientists can determine not just which genes exist but which genes were functioning in specific tissues at specific times. DNA gives you the library; RNA shows you which books were being read.

Until recently, ancient RNA seemed impossibly fragile. The molecule degrades rapidly after death, typically surviving only hours under normal conditions. DNA, more chemically stable, was considered the only genetic material that could survive for millennia. Ancient DNA studies have transformed our understanding of human evolution, revealing interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans, tracing migrations, and reconstructing family trees. But these studies could only tell us about genes, not gene expression. They revealed the script but not the performance.

The mammoth RNA discovery overturned this assumption. The Swedish team demonstrated that under the right conditions, specifically the constant freezing of permafrost, RNA can persist for tens of thousands of years. This means ancient RNA studies are possible, and the implications for understanding extinct species are profound.

A Mammoth Surprise

The research team didn’t just examine Yuka. They screened tissue samples from ten mammoths preserved in Siberian permafrost, each dated to between 39,000 and 52,000 years old. After filtering out contamination from environmental sources and modern handling, they successfully identified ancient RNA from three specimens. The recovery rate wasn’t high, but the fact that any RNA survived that long challenged conventional wisdom about molecular preservation.

The RNA sequences revealed which genes were active in the mammoths’ preserved tissues. In skin samples, genes related to skin maintenance and hair growth were expressed, exactly what you’d expect from functioning skin tissue. In muscle samples, genes for muscle proteins were active. The tissue-specific patterns confirmed that the RNA was genuine, reflecting actual biological activity rather than random contamination.

One finding came as a particular surprise. The researchers detected RNA sequences from genes located exclusively on the Y chromosome. This was unexpected because scientists had long assumed Yuka was female based on the specimen’s size and anatomy. The Y chromosome RNA suggested otherwise. Either Yuka was male, or the specimen contained tissue from multiple individuals. The discovery illustrates how RNA analysis can reveal information that DNA sequencing alone would miss.

Perhaps most remarkably, the team recovered microRNAs from the ancient samples. These tiny molecules, typically about 22 nucleotides long, regulate gene expression by fine-tuning protein production. They’re crucial to cellular function but notoriously difficult to preserve because of their small size and chemical fragility. Finding them in 40,000-year-old tissue was unexpected and significant. MicroRNAs help explain how genes are regulated, adding another layer of biological information to ancient genetic studies.

The Permafrost Library

The success of the mammoth RNA recovery depended on exceptional preservation conditions. Siberian permafrost, ground that remains frozen year-round, creates a natural deep freeze that dramatically slows molecular degradation. Yuka’s body was essentially flash-frozen and kept at temperatures well below zero for millennia, protecting RNA molecules that would have degraded within hours under normal conditions.

This raises an intriguing possibility: the permafrost may contain an enormous library of ancient RNA waiting to be read. Thousands of Ice Age specimens have been recovered from Siberia and other permafrost regions, including mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, cave lions, steppe bison, and ancient wolves. Many are held in museum collections around the world. The masters of the cold left behind not just bones but frozen time capsules. If RNA can survive under permafrost conditions, these specimens may yield not just DNA but active gene expression data.

The implications extend beyond extinct megafauna. Researchers have suggested that ancient RNA studies might allow us to sequence RNA viruses from Ice Age specimens. Influenza, coronaviruses, and other pathogens leave traces in their hosts. If those traces include RNA, we might be able to reconstruct ancient viral genomes and trace viral evolution back tens of thousands of years. Understanding how viruses evolved could provide insights into future pandemic preparedness.

The permafrost library faces a threat, however: climate change. As global temperatures rise, permafrost that has been frozen for millennia is beginning to thaw. Specimens that have been preserved for tens of thousands of years are at risk of degradation. The race to study ancient RNA is also a race against warming temperatures. What took nature 40,000 years to preserve, climate change could destroy in decades.

From Reading to Writing

The mammoth RNA discovery arrives at a moment when de-extinction science is advancing rapidly. Companies like Colossal Biosciences are attempting to use genetic engineering to revive extinct species, including the woolly mammoth. Their approach involves editing the genome of living elephants to incorporate mammoth genes, essentially reverse-engineering mammoth traits into elephant embryos. The project has been controversial, raising questions about ethics, ecology, and whether the result would truly be a mammoth or merely an elephant with mammoth features.

RNA data doesn’t resolve these debates, but it significantly advances the science. Understanding which genes were active in living mammoths, not just which genes existed, is crucial for recreating mammoth biology. A genome alone is like sheet music; you also need to know how it was performed. Which genes should be expressed in mammoth skin to produce thick fur? Which should be active in fat tissue to generate the cold resistance that allowed mammoths to thrive in Ice Age winters? DNA provides the list of possibilities; RNA shows which possibilities were actually used.

Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary biologist who serves as chief scientific officer at Colossal Biosciences, called the ancient RNA recovery “a crucial scientific milestone” for de-extinction efforts. The more researchers understand about how mammoth genes actually functioned, the better equipped they’ll be to recreate those functions in modified elephant genomes. Perfect resurrection may remain impossible, but functional approximation becomes more achievable with each advance in ancient genetics.

The same principles apply to other de-extinction candidates. The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, went extinct in 1936, and specimens exist in museum collections. In 2023, researchers successfully recovered RNA from a thylacine specimen over a century old, despite room-temperature preservation. The findings identified thylacine-specific microRNA variants and revealed tissue-specific gene expression patterns. Combined with existing DNA data, this RNA information brings functional reconstruction of the thylacine closer to possibility.

What Ancient RNA Can Tell Us

Beyond de-extinction, ancient RNA opens new research directions that DNA alone cannot address. Consider the question of how extinct species lived and died. DNA can identify a species and trace its lineage, but it reveals nothing about individual lives. RNA, reflecting gene expression at the moment of death, provides a biological snapshot of the organism’s final state.

For Yuka, the RNA data suggested normal tissue function in the hours before death. The mammoth wasn’t obviously sick; its genes were expressing normally for skin and muscle tissue. This is a single data point, but across many specimens, patterns might emerge. Did mammoths that died during cold snaps show different gene expression than those that died in summer? Did some individuals show signs of disease or stress in their final gene expression? These questions become answerable with RNA data in ways they never were with DNA alone.

The technique also promises to improve our understanding of evolutionary history. RNA can identify genes that DNA sequencing missed or misidentified. When researchers reconstructed the thylacine’s transcriptome, they found genes that previous DNA assemblies had failed to annotate correctly. The RNA data provided a correction layer, improving the genome map. For species known only from fragmentary remains, RNA might reveal genetic features that DNA evidence obscured.

There’s also the simple expansion of what’s possible. Before the mammoth study, ancient RNA from specimens over a few thousand years old seemed unlikely. The 40,000-year threshold demolished that assumption. What other assumptions about molecular preservation might be wrong? The history of paleogenetics has been a series of barriers broken: ancient DNA was impossible until it wasn’t; Neanderthal genome sequencing was impossible until it wasn’t; and now ancient RNA from the Ice Age has joined the list. The field has learned to be cautious about declaring anything impossible.

The Bigger Picture

The recovery of 40,000-year-old mammoth RNA represents more than a technical achievement. It marks the emergence of paleotranscriptomics as a viable scientific field, one that can tell us not just what extinct species were but what they were doing. The difference is profound. Anatomy shows us form. DNA shows us potential. RNA shows us function. For the first time, we can ask questions about the active biology of species that disappeared before recorded history.

The discovery also connects to broader themes about preservation and loss. The ongoing discovery of new species reminds us that biodiversity extends beyond what we’ve catalogued. The RNA findings suggest that even extinct species aren’t entirely lost; traces of their living biology may persist in preserved remains, waiting for techniques sophisticated enough to read them.

At the same time, the permafrost that preserved Yuka is itself threatened. The same climate change that concerns contemporary conservationists is destroying the natural freezers that kept Ice Age RNA intact. There’s an urgent irony in this: we’re developing the ability to read ancient molecular messages just as the conditions that preserved them are beginning to fail.

What Yuka offers, beyond scientific data, is a glimpse of a vanished world. Forty thousand years ago, a young mammoth walked the Siberian steppe. It ate, grew, survived winters, and eventually died. Its body froze into the permafrost and waited across millennia, through the rise and fall of ice sheets, through the emergence of human civilization, through the development of molecular biology and genetics. Now, in the early 21st century, we can finally read the molecular traces of its final hours. The mammoth couldn’t know that its preserved tissues would one day reveal which of its genes were active at the moment it died. But that information, extracted from 40,000-year-old RNA, connects us to an individual life from the deep past in ways that seemed impossible until very recently.

The oldest RNA ever found tells us about more than mammoths. It tells us that the past is more accessible than we assumed, that life leaves traces more durable than we expected, and that the boundary between living and extinct may be more permeable than we thought. What other messages from deep time are waiting to be read?