We know more about the surface of Mars than we do about the Denisovans. Until 2010, nobody even knew they existed. Then a single finger bone from a Siberian cave upended everything we thought we understood about human evolution. Here was a previously unknown species of human, identified not from skulls or skeletons but from fragments of DNA preserved in tiny bone chips.

Now, a tooth found in that same cave has pushed our understanding back another hundred thousand years. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology have sequenced the oldest high-coverage genome ever recovered from an ancient human, belonging to a Denisovan man who lived approximately 200,000 years ago. The findings, published as a preprint in late 2025, reveal not just one population of mysterious human relatives but a web of interbreeding that extended across continents and deep into time.

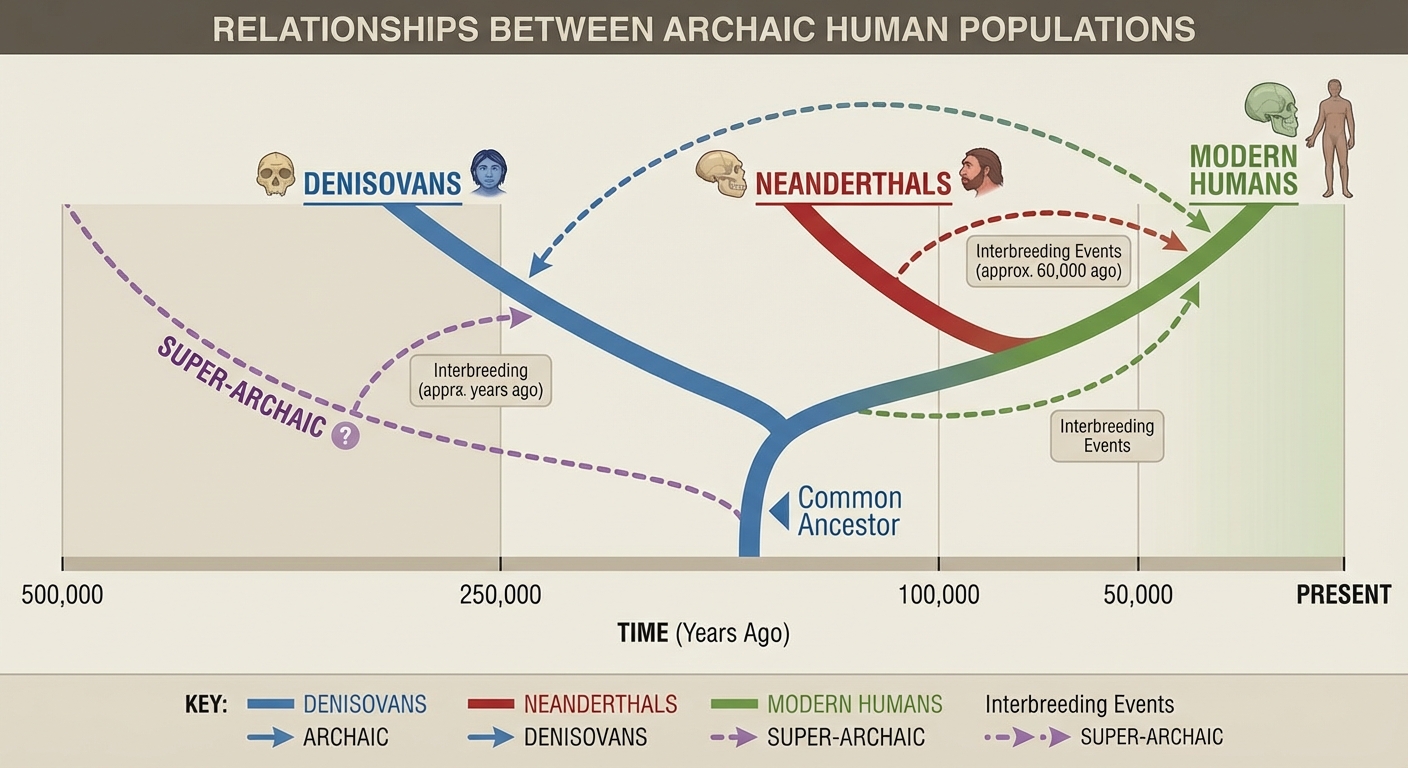

What that single tooth reveals is staggering: the Denisovans weren’t one group but many, genetically distinct populations spread across Asia. They interbred with Neanderthals, with early modern humans, and with an even more ancient “super-archaic” population that split from our family tree before any of these groups diverged. And traces of all these ancient encounters survive in people alive today.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

In 2008, Russian archaeologists working in Denisova Cave, a limestone cavern in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, found a fragment of finger bone in a layer of sediment dating to roughly 50,000 years ago. The bone was too small to tell researchers much through traditional analysis. But when Svante Pääbo’s team at the Max Planck Institute extracted DNA from the fragment, they found something extraordinary: mitochondrial DNA unlike that of any known human species.

The DNA didn’t match modern humans. It didn’t match Neanderthals. It represented a previously unknown branch of the human family tree that had diverged from our lineage roughly a million years ago. With only fragments to work from and almost no fossil evidence, researchers named this new group after the cave where they were found. The Denisovans had been hiding in plain sight, their existence written in ancient DNA rather than bones.

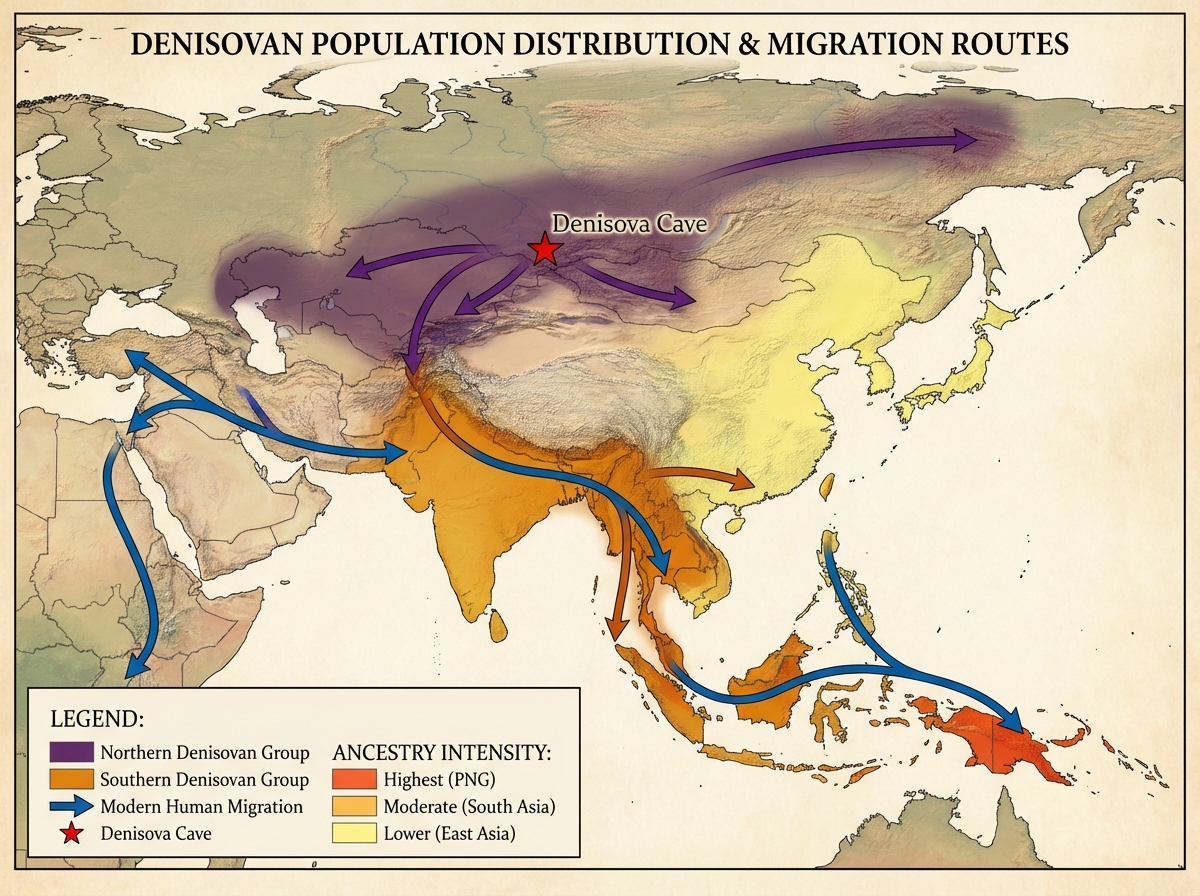

Over the following years, only a handful of Denisovan remains have been identified: a few teeth, the original finger bone, and a piece of skull. Yet the genetic legacy of these elusive humans lives on. When researchers compared Denisovan DNA to modern populations, they found that people living in Melanesia, Papua New Guinea, and Aboriginal Australia carry up to 5% Denisovan DNA in their genomes. The Denisovans may have left few bones, but they left descendants.

The Oldest Genome Ever Sequenced

In 2020, archaeologists working in the deepest cultural layers of Denisova Cave found a complete upper molar. Layer 17, where the tooth was discovered, dates to between 200,000 and 170,000 years ago, making any remains found there far older than previously studied Denisovan specimens.

The tooth belonged to a man. Researchers designated him Denisova 25, and against considerable odds, they managed to extract enough DNA to sequence his entire genome at high coverage, approximately 23.6 times. This means each position in his genetic code was read an average of 23.6 times, providing the same level of detail scientists expect from modern DNA samples.

This isn’t just the oldest Denisovan genome. It’s the oldest high-coverage genome ever recovered from any ancient human. The previous record holder, a roughly 80,000-year-old Denisovan woman from the same cave, now seems almost recent by comparison. Denisova 25 lived more than twice as long ago, in a world where multiple human species shared the planet and regularly encountered one another.

What the Genome Reveals

The genome of Denisova 25 tells a complex story of migration, isolation, and interbreeding. This 200,000-year-old man belonged to a small, isolated Denisovan population that had already mixed with early Neanderthals. But his group was eventually replaced by later Denisovans who carried different Neanderthal DNA, evidence of a second wave of interbreeding between these two human lineages.

Even more surprising was evidence of an encounter with an unknown population, one that researchers call “super-archaic” humans. This group split from the human family tree before the ancestors of Denisovans, Neanderthals, and modern humans diverged from one another. We don’t know who they were. We have no fossils that clearly belong to them. But their genetic signature survives in the Denisovan genome, ghost ancestors whose existence we can detect only through the traces they left in other species’ DNA.

The two high-quality Denisovan genomes now available allow researchers to untangle Denisovan ancestry in people alive today. The picture that emerges is more complicated than anyone expected. Modern humans didn’t encounter just one group of Denisovans. They encountered at least three genetically distinct populations at different times and places.

The Denisovan Diaspora

Perhaps the most remarkable finding concerns how Denisovan DNA ended up in modern populations. People in Oceania, including Papua New Guinea, Aboriginal Australia, and Melanesia, carry substantial Denisovan ancestry. So do some populations in South Asia. But the Denisovan DNA in these groups doesn’t match. Oceanians and South Asians inherited their Denisovan ancestry independently, from a deeply diverged Denisovan population that was likely isolated somewhere in South Asia.

This means Denisovans weren’t confined to Siberia. They spread across Asia, diversifying into genetically distinct groups that remained separate long enough to accumulate substantial differences. When modern humans expanded out of Africa, they encountered these different Denisovan populations in different places, each encounter leaving its own genetic signature.

East Asians present another puzzle. Despite living in a region where Denisovans must have been present, they carry less Denisovan ancestry than Oceanians and lack the South Asian Denisovan component entirely. This suggests their ancestors may have taken a different route into Asia, perhaps moving north through Central Asia rather than south through the subcontinent, arriving after Denisovans had already disappeared from the regions they passed through.

Why This Matters

The story emerging from ancient DNA is one of a crowded prehistoric world where multiple human species coexisted, competed, and sometimes had children together. Our ancestors didn’t spread across an empty planet. They moved into landscapes already occupied by other humans, relatives who had left Africa hundreds of thousands of years earlier and adapted to environments from tropical forests to frozen steppes.

The Denisovans gave modern humans more than just interesting ancestry percentages. They gave us genes. Some Denisovan DNA that survives in modern populations appears to have been preserved by natural selection because it provided advantages. Tibetans carry a Denisovan gene variant that helps them survive at high altitudes. Indigenous Australians may carry Denisovan immune genes adapted to tropical pathogens.

Understanding who the Denisovans were, where they lived, and how they interacted with other human populations isn’t just academic curiosity. It illuminates the process by which we became who we are, a species forged through countless encounters with relatives who no longer exist except in the fragments of their DNA that we still carry.

The Bigger Picture

A single tooth, smaller than a marble, has revealed more about human prehistory than decades of traditional archaeology could provide. The Denisovans remain frustratingly invisible in the fossil record, known primarily through genetic traces rather than physical remains. We don’t know what they looked like beyond rough inferences from DNA. We don’t know how they lived, what they ate, or whether they made art or buried their dead.

But we know they were real. We know they spread across Asia, diversified into multiple populations, and encountered both Neanderthals and our own ancestors. We know they carried genes from even more ancient humans, populations so mysterious we can detect them only through their ghostly genetic signature in Denisovan DNA. And we know that when they disappeared, they didn’t vanish entirely. Traces of them survive in billions of people alive today, an inheritance from relatives we met only once and remember not at all.

The Denisova 25 genome opens a window 200,000 years into the past, to a time when multiple human species shared the planet and our own ancestors hadn’t yet left Africa. What we see through that window is not a simple family tree but a tangled network of populations splitting, merging, and exchanging genes across hundreds of thousands of years. Human evolution wasn’t a ladder. It was a river delta, with channels splitting and rejoining in patterns we’re only beginning to map.

Sources: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology research team, bioRxiv preprint (October 2025), Denisova Cave archaeological excavations, paleogenetic analysis of archaic human populations.