The collision happened 17 billion years ago, when the universe was less than half its current age. Two black holes, each more massive than 100 suns, spiraled toward each other and merged in a cataclysm that released more energy than all the stars in the observable universe combined, if only for an instant. The resulting black hole weighs approximately 225 times the mass of our sun.

We detected this event only recently, when the gravitational waves it produced finally reached Earth after crossing billions of light-years of space. The LIGO and Virgo observatories picked up the distinctive chirp of merging black holes, and analysis revealed something unexpected. The black holes that merged were too massive to have formed through ordinary stellar evolution. According to standard theory, they shouldn’t exist.

The detection challenges physicists to explain how such massive black holes formed in the first place. Every theory has problems. Maybe our understanding of stellar physics is incomplete. Maybe these black holes formed through unusual channels we haven’t fully explored. Maybe they’re remnants of the earliest stars, monsters from the cosmic dawn when different rules applied. The 225-solar-mass black hole is real, whatever its origin. Explaining it is now the challenge.

The Mass Gap Problem

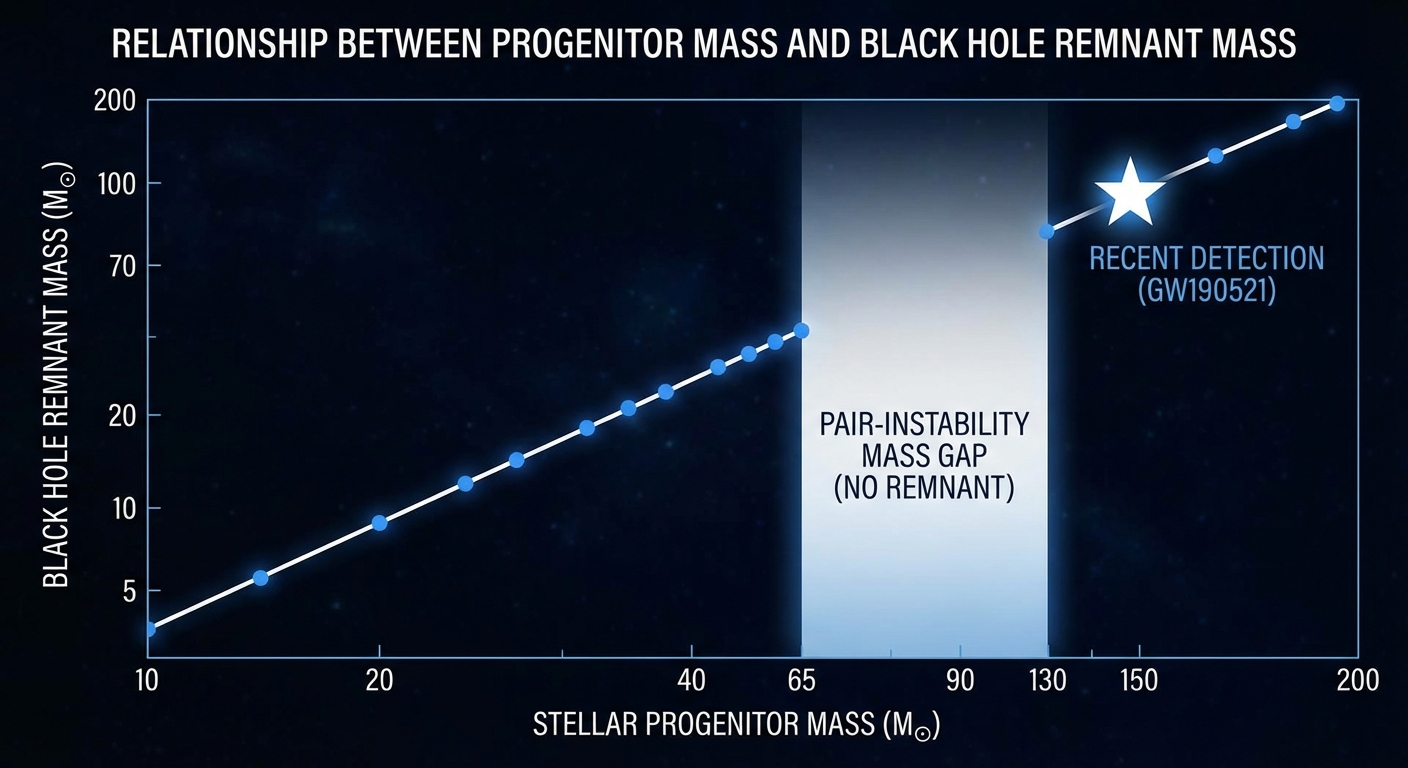

When massive stars die, they can collapse into black holes. But not all massive stars produce black holes, and the masses of the black holes they produce follow patterns. Stars in a certain mass range, roughly 65 to 130 times the sun’s mass, are predicted to end their lives in a particular way: they undergo a process called pair-instability supernova that completely destroys the star, leaving nothing behind. No remnant, no black hole.

This creates what physicists call the “pair-instability mass gap.” Black holes formed from stellar collapse should have masses either below about 65 solar masses or above about 130 solar masses. The region in between should be empty, a forbidden zone where black holes don’t form through standard channels.

The black holes detected in the recent merger were both in or above this forbidden range. Each one had a mass exceeding 100 solar masses. According to pair-instability theory, they couldn’t have formed through normal stellar evolution. Either they formed through some other process, or our understanding of massive star deaths is incomplete.

This isn’t the first detection of black holes in the mass gap, but it’s the most extreme. Previous detections could be explained as borderline cases, massive but just barely plausible. The 225-solar-mass merger is harder to dismiss. The parent black holes were unambiguously too massive to have formed through standard stellar collapse.

How Gravitational Waves Work

Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime itself, produced when massive objects accelerate. Einstein predicted them in 1916 as a consequence of general relativity. When two black holes orbit each other, they create gravitational waves that carry energy away from the system. As energy leaves, the black holes spiral closer together, orbit faster, and produce stronger waves. Eventually they merge, releasing a final burst of gravitational radiation.

The waves travel at the speed of light, stretching and squeezing space as they pass. By the time they reach Earth, they’ve spread across billions of light-years, weakening to almost undetectable levels. The LIGO and Virgo detectors can sense changes in distance smaller than a proton’s width, allowing them to pick up these incredibly faint signals.

The signal from the 225-solar-mass merger arrived as a characteristic “chirp,” a wave pattern that rises in frequency and amplitude as the black holes spiral together, ending in a sudden peak when they merge. The shape of this signal encodes information about the masses of the merging objects, their spins, and the distance to the event. Analyzing the chirp is like reading a fingerprint, revealing the properties of objects billions of light-years away.

The merger released about 7 solar masses worth of energy as gravitational waves, converted directly from the mass of the colliding black holes according to Einstein’s E=mc². For a brief moment, the power output exceeded the combined luminosity of all stars in the observable universe. Yet because gravitational waves interact so weakly with matter, this apocalyptic energy passed through the cosmos almost unnoticed, detectable only by the most sensitive instruments humanity has ever built.

Possible Explanations

If these massive black holes didn’t form through standard stellar collapse, how did they form? Several possibilities are being explored.

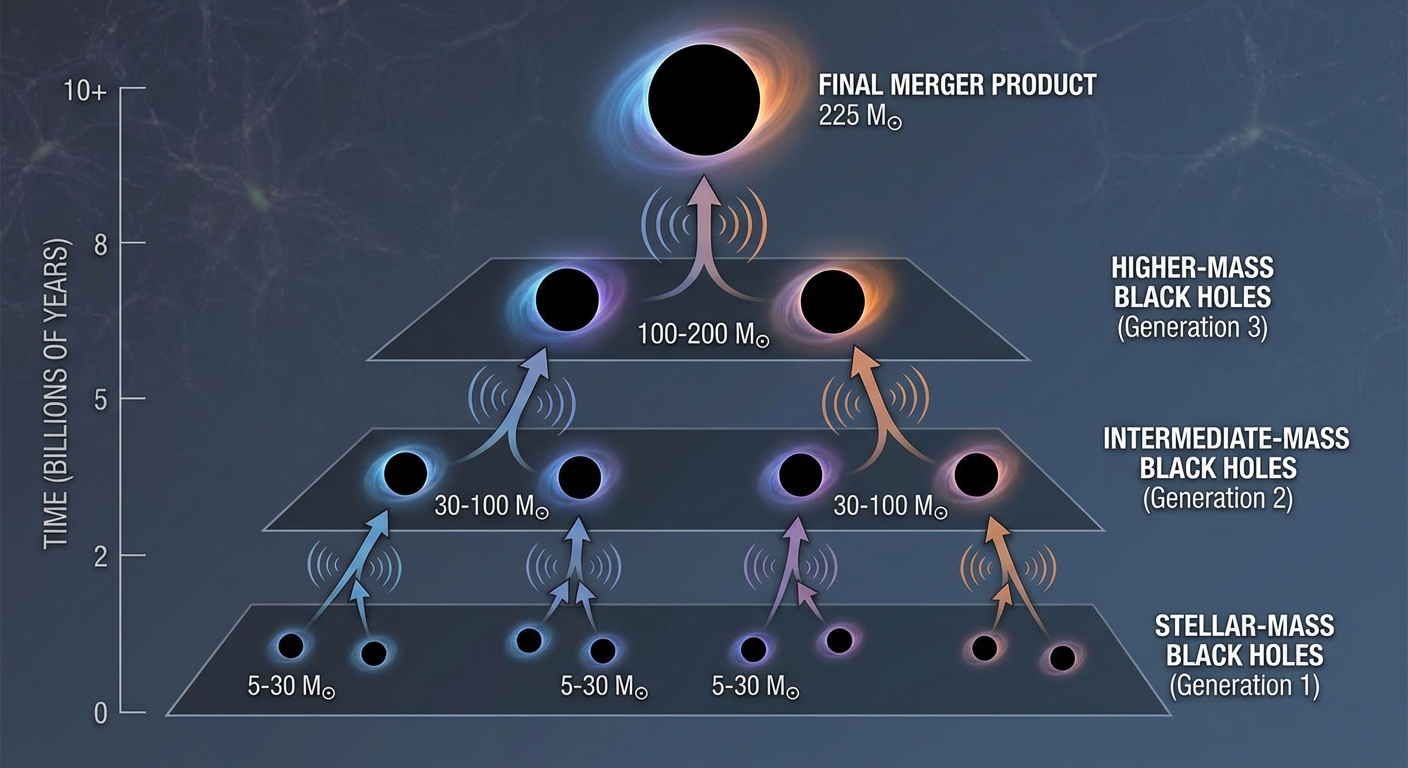

One theory suggests they’re second-generation black holes, the products of previous mergers. A black hole formed from stellar collapse might have merged with another black hole to create a larger one, which then merged again, and so on. Through repeated mergers over billions of years, black holes could grow to masses that no single star could produce. This hierarchical growth could explain masses in the forbidden gap.

Another possibility involves primordial black holes, hypothetical objects that could have formed in the very early universe, before stars existed. If density fluctuations in the primordial plasma were large enough, regions of space could have collapsed directly into black holes. These primordial black holes wouldn’t be subject to the mass limits that apply to stellar collapse because they didn’t form from stars.

A third possibility is that our understanding of pair-instability supernovae is incomplete. Perhaps certain conditions, unusual stellar compositions, rapid rotation, or binary interactions, allow massive stars to avoid complete destruction and instead collapse into black holes in the forbidden mass range. The physics of stellar explosions is complex, and surprises remain possible.

What This Means

The 225-solar-mass black hole detection matters because it tests our theories in extreme conditions. Physics works well for describing black holes in certain mass ranges where we have multiple detections and good theoretical understanding. But extreme cases push theories to their limits, potentially revealing new physics or forcing revisions to existing models.

The detection also demonstrates what gravitational wave astronomy can achieve. Before LIGO’s first detection in 2015, we had never directly observed gravitational waves. Now we routinely detect black hole mergers across the universe, learning about objects and events that are completely invisible to telescopes. Each detection adds to our statistical understanding of black hole populations, their masses, spins, and merger rates.

In the coming years, more sensitive detectors and space-based observatories will expand our reach. We’ll detect more mergers, including rarer events involving the most massive black holes. The population of known black holes will grow from dozens to hundreds to thousands, allowing precise tests of theories that single detections can only hint at.

The Bigger Picture

Seventeen billion years ago, two monsters collided in a distant part of the universe. The gravitational waves from that collision traveled for most of the universe’s history before reaching Earth, where instruments sensitive enough to detect them had existed for only a few years. The detection represents a kind of cosmic archaeology, using ripples in spacetime to learn about events that occurred before our solar system formed.

The 225-solar-mass black hole challenges our theories but doesn’t break them. Physics is robust enough to accommodate surprises while flexible enough to revise when evidence demands. The mass gap may turn out to be less of a gap than we thought, or the black holes in question may have formed through channels we’re only beginning to understand.

What’s certain is that the universe continues to surprise us. Every time we develop new ways of observing it, we find phenomena that push the boundaries of our understanding. Gravitational wave astronomy is barely a decade old. The strangest discoveries are likely still ahead.

Sources: LIGO/Virgo Collaboration gravitational wave detection analysis, pair-instability supernova theory research, hierarchical black hole merger models, primordial black hole formation hypotheses, gravitational wave signal processing studies.