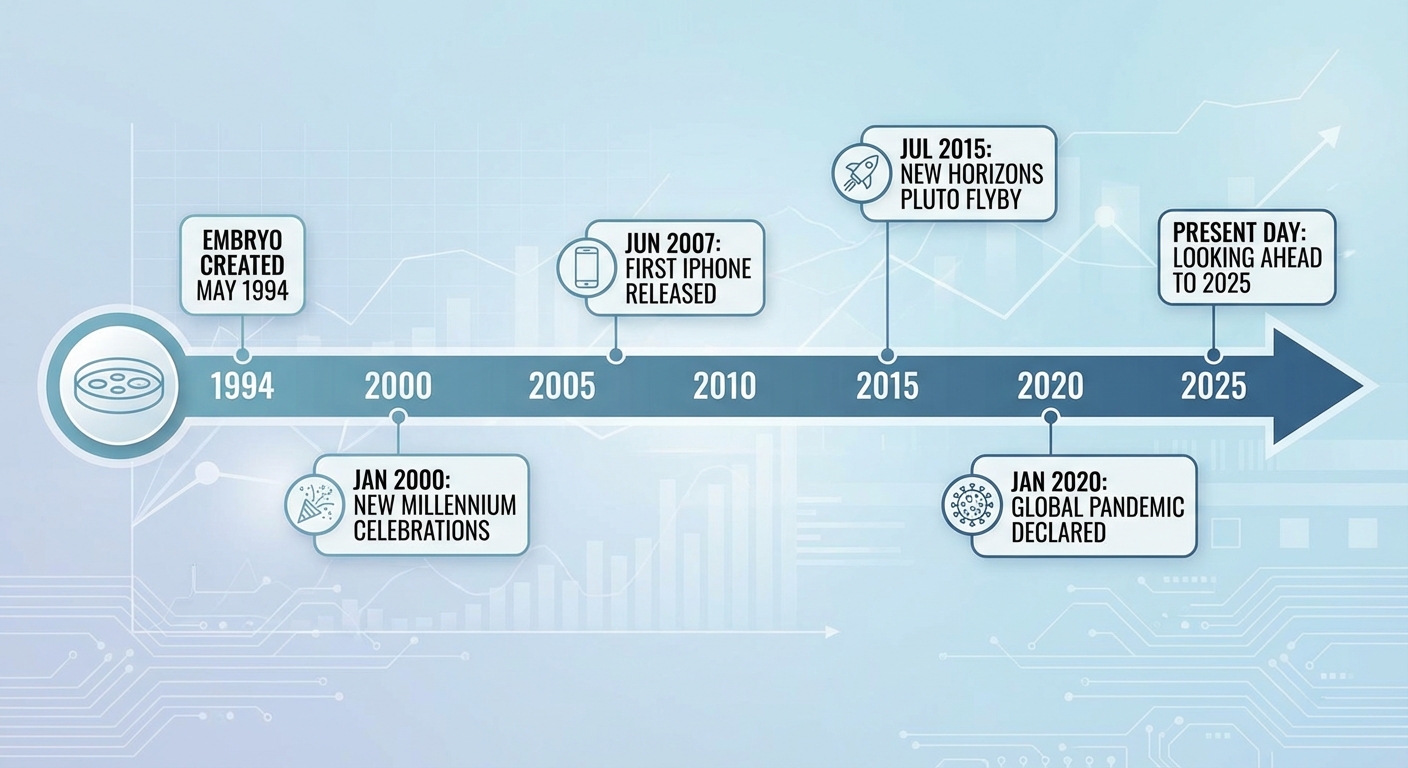

The baby born in July 2025 was, in a sense, older than both of her parents. Conceived in May 1994, the embryo had been frozen and stored for over 30 years before being thawed, implanted, and carried to term by a couple who were themselves toddlers when the embryo was created. The original parents, who had successfully conceived through IVF in the 1990s, donated their remaining embryos. Decades later, one of those embryos became a person.

The case breaks previous records for the longest-frozen embryo to result in a live birth, though such records are broken periodically as the frozen embryo population ages. More significantly, it raises questions that reproductive technology has outpaced our ability to answer. What does it mean to have biological parents you’ve never met and were strangers to your birth parents? How should we think about siblings born decades apart to different families? The technology of embryo preservation works reliably. The social and ethical frameworks for understanding it are still catching up.

The 30-year embryo is an extreme case, but it represents a broader reality: there are millions of frozen embryos in storage worldwide, and the number grows every year. Each one is a potential person in suspended animation, waiting for decisions that may never be made or may come from people the original creators never imagined.

How Embryo Freezing Works

Embryo cryopreservation has been routine in fertility medicine since the 1980s. When couples undergo IVF, clinicians typically fertilize multiple eggs to increase the chances of success. This often produces more viable embryos than can be safely implanted in a single cycle. The extras are frozen for potential future use.

The freezing process itself has improved dramatically. Early methods used slow cooling that allowed ice crystals to form inside cells, sometimes damaging them. Modern vitrification, developed in the 2000s, cools embryos so rapidly that water turns directly to a glass-like solid without crystallizing. Survival rates after thawing now exceed 95%, and babies born from vitrified embryos show no difference in health outcomes from those conceived fresh.

Once frozen at minus 196 degrees Celsius in liquid nitrogen, embryos enter a state of suspended animation. Metabolic processes halt completely. In theory, a frozen embryo could remain viable indefinitely, as there’s no degradation occurring at those temperatures. The practical limit is set by storage facilities and the choices of embryo owners, not by biological deterioration.

The 30-year embryo was frozen using the earlier slow-cooling method, which makes its successful development even more remarkable. It survived not only three decades of storage but a freezing process that modern techniques have since improved upon. The embryo was resilient, or lucky, or both.

The Families Involved

The original parents created the embryo in 1994 as part of their IVF treatment. After successfully having their own children, they chose to donate their remaining embryos rather than discard them or keep them frozen indefinitely. Many couples in their position face this difficult choice. Some feel that embryos represent potential life and cannot ethically be destroyed. Others find indefinite storage unsettling, paying annual fees to maintain genetic material they’ll never use.

Embryo donation allows couples who cannot conceive with their own genetic material to experience pregnancy and birth. The receiving parents have no genetic relationship to the child, similar to adoption, but they carry the pregnancy themselves. This creates a unique form of family building that combines elements of adoption and biological parenthood without matching either one exactly.

The receiving parents in this case were born in the early 1990s, making them approximately the same age as the embryo they adopted. In a biological sense, their daughter could have been their peer. She shares no genes with them but shares a birth year with genetic siblings she may never meet, people now in their 30s who were born from the same IVF cycle but decades earlier.

These relationships have no historical precedent. Human kinship systems evolved to handle the complexities of biological parenthood, step-parenthood, and adoption. They have no ready-made categories for siblings separated by 30 years and raised by different families, or for genetic parents who are a generation older than the people who actually raise the child.

The Frozen Population

The 30-year embryo isn’t alone in its extended suspended animation. Fertility clinics worldwide store an estimated 4 to 5 million frozen embryos, and the number grows each year. Many will eventually be thawed for use by their original creators or donated to other families. Some will be donated for research. Many more sit in indefinite storage, their creators unable or unwilling to decide their fate.

The stored embryos represent a kind of deferred potential. Each one could theoretically become a person, given the right decisions and circumstances. But most won’t. Studies suggest that a significant majority of frozen embryos will never be used for reproduction, either because their creators complete their families without needing them, because the creators divorce and can’t agree on disposition, or because the storage fees lapse and the embryos are eventually discarded or donated to research.

The legal status of frozen embryos varies widely. Some jurisdictions treat them as property that can be divided in divorce like other assets. Others grant them special status as potential persons, with implications for who can make decisions about their fate. A few countries limit how long embryos can be stored before they must be either used or destroyed. The United States has relatively few regulations, leaving most decisions to fertility clinics and the families who created the embryos.

Questions Without Easy Answers

The case of the 30-year embryo brings into focus questions that have been building since reproductive technology began outpacing our ethical frameworks. The technology works, but what should we do with it?

One question concerns genetic siblings. The baby born in 2025 may have full genetic siblings who were born in the 1990s, raised by different parents, and have lived complete lives as adults while she was still frozen. Should they know about each other? Should they have the opportunity to meet? Donor-conceived people have increasingly sought out their genetic relatives, finding half-siblings through DNA testing services. The 30-year age gap makes such relationships even more unusual.

Another question concerns the original genetic parents. They made their contribution three decades ago and have presumably moved on with their lives. Their genetic offspring is being raised by strangers. Do they have any relationship to this child, even if they have no legal rights or responsibilities? The moral intuition that genetic connection matters runs deep, but the 30-year embryo case stretches that intuition to its breaking point.

The Bigger Picture

The frozen embryo represents a fundamental change in human reproduction that we’re still processing. For all of human history, conception and birth were temporally linked. The gap between them was nine months, give or take. Now that gap can be decades. The biological event of fertilization and the social event of birth have been decoupled, creating new possibilities and new confusions.

The 30-year record will eventually be broken. Somewhere in a cryogenic tank sits an embryo that will someday be thawed, implanted, and born to parents who weren’t conceived when it was created. The technical capability exists for embryos frozen today to be born a century from now, carried by people not yet born themselves.

We have created a kind of time travel, though not the dramatic kind from science fiction. It’s a one-way journey into the future, traveled by the smallest possible passengers. The implications ripple outward: for families, for identity, for how we understand what it means to be born at a particular time and place. The frozen embryos wait in their cryogenic storage, holding potential futures we’re only beginning to understand.

Sources: Fertility clinic cryopreservation records, embryo donation program data, vitrification technique research, legal frameworks for reproductive technology, demographic studies of frozen embryo populations.