In the ice ages that ended roughly 11,000 years ago, dire wolves roamed North America as apex predators. Larger and more robust than modern gray wolves, with powerful jaws capable of crushing bone, they hunted megafauna across a continent that would soon lose most of its large mammals. When the ice age ended and their prey disappeared, the dire wolves vanished with them, leaving behind only fossils, most famously the thousands of individuals preserved in the La Brea tar pits.

Now, a biotech company claims to have brought them back. Colossal Biosciences announced that it has created the first modern dire wolves: two males named Romulus and Remus, and a female called Khaleesi. Using DNA extracted from ancient specimens and gene-editing technology, the company says it has produced animals that carry the key genetic signatures of their ice age ancestors.

If the claims hold up to scientific scrutiny, this represents a threshold moment in biotechnology. We have crossed from imagining de-extinction to achieving it. And the implications, for biology, for ethics, and for our relationship with the natural world, are only beginning to come into focus.

How They Did It

The science behind the dire wolf resurrection draws on two parallel advances: our ability to extract and sequence ancient DNA, and our ability to edit the genomes of living organisms.

Colossal’s team sequenced the dire wolf genome from two specimens: a 13,000-year-old tooth and a 72,000-year-old skull. Ancient DNA is typically fragmented and degraded, requiring sophisticated computational techniques to piece together complete sequences. The team identified 14 genes that differ significantly between the extinct dire wolves and modern canids, focusing on genes that affect size, skull structure, jaw strength, and other traits that made dire wolves distinctive.

They then used CRISPR-based gene editing to introduce these ancient gene variants into the genome of a modern surrogate. The details of the surrogate species haven’t been fully disclosed, though the most likely candidate is a domestic dog, possibly a large breed that could carry puppies to term and provide a reasonable maternal environment for the engineered embryos.

The resulting animals aren’t technically clones of any ancient individual. They’re chimeras, carrying modern genomes that have been edited to include key dire wolf traits. Whether they’re “really” dire wolves is partly a philosophical question. They carry the genetic variants that made dire wolves distinctive, but much of their genome remains modern.

What the Dire Wolves Look Like

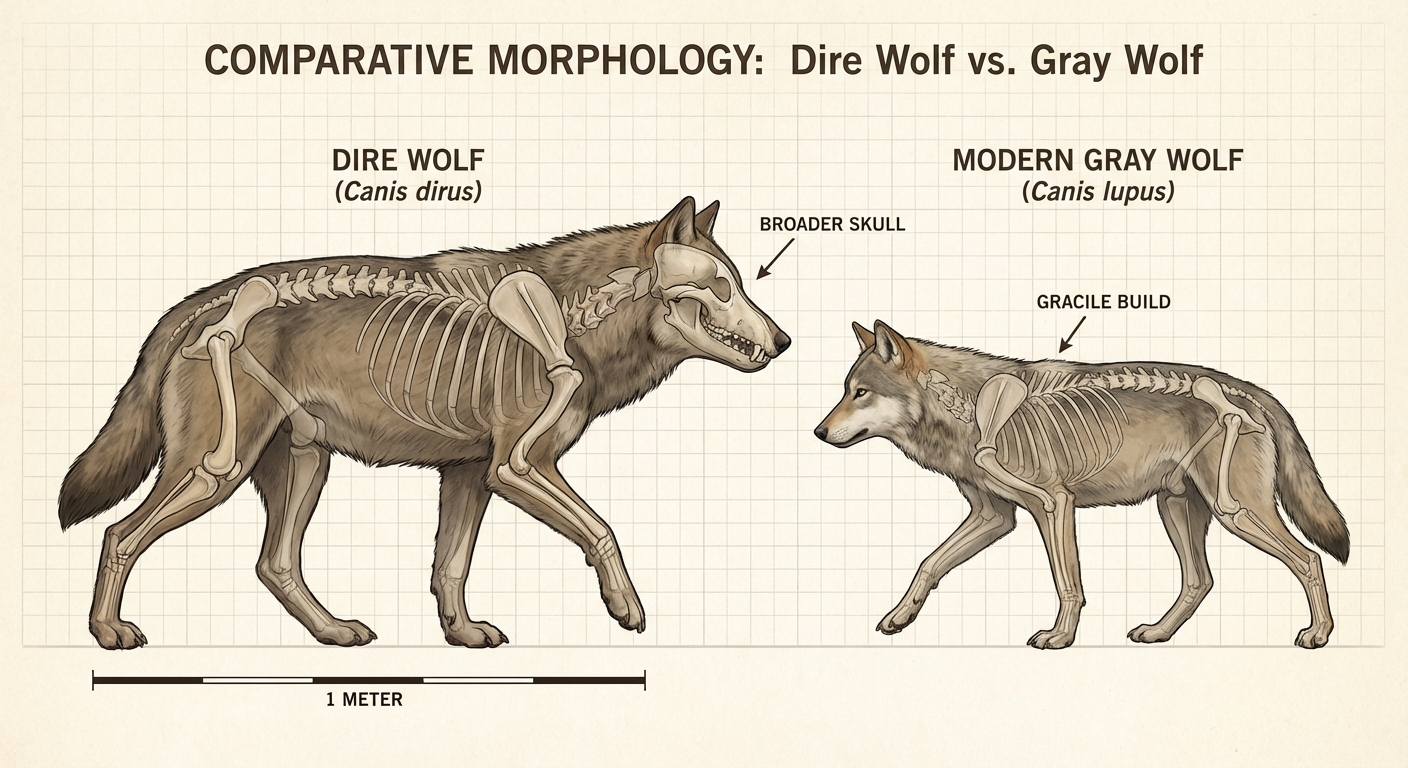

According to Colossal’s descriptions, Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi are noticeably larger than modern gray wolves, with broader skulls and more powerful jaws. These features align with what paleontologists know about dire wolf anatomy from fossil evidence. The animals also differ from gray wolves in coat color and other visible traits, though it’s unclear which of these differences reflect ancient genetics versus variation in the surrogate lineage.

The animals are being kept in a controlled facility and are not available for independent verification. Colossal has released photographs and video, but the scientific community has called for peer-reviewed publication of the genomic data and methodology before accepting the claims at face value. Previous de-extinction announcements have sometimes overstated what was actually achieved, and extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Still, the technology is clearly advancing. Even if this specific announcement proves exaggerated, the fundamental capability to introduce ancient genetic variants into modern organisms is real and improving rapidly. If Colossal hasn’t quite resurrected the dire wolf, someone probably will soon.

The Science of De-Extinction

De-extinction sits at the intersection of several technologies that have advanced dramatically in recent years. Ancient DNA extraction has improved to the point where we can recover genetic material from specimens tens of thousands of years old, sometimes older if preservation conditions were favorable. Sequencing technology can handle the fragmented, damaged DNA that ancient samples yield. And gene-editing tools, particularly CRISPR-Cas9 and its successors, can introduce specific changes to living genomes with increasing precision.

The dire wolf is a relatively tractable target for these technologies. Wolves are well-studied mammals with complete modern genome references for comparison. The specimens available for DNA extraction are relatively young in geological terms, meaning the DNA is better preserved than it would be from more ancient species. And wolves can interbreed with dogs, providing flexible options for surrogate gestation.

Other species present greater challenges. The woolly mammoth, Colossal’s most publicized target, is more complex because elephants have longer generation times, produce fewer offspring, and present ethical concerns about using endangered Asian elephants as surrogates. Mammoths went extinct more recently than dire wolves but still present significant DNA degradation issues.

Some species may be impossible to resurrect with current or foreseeable technology. The more time since extinction, the more degraded the DNA. The more different the extinct species from any living relative, the harder it is to find a suitable surrogate. And some extinctions left no recoverable DNA at all, only bones and fossils that preserve shape but not genetic material.

Why Resurrect Extinct Species?

Colossal and other de-extinction advocates offer several justifications. First, there’s the argument from scientific knowledge: by recreating extinct species, we learn about their genetics, physiology, and ecology in ways that fossil study alone cannot reveal. Living dire wolves could answer questions about ice age ecosystems that bones cannot.

Second, there’s the ecological argument. Many extinct species played important roles in their ecosystems, and their absence has cascading effects. Some rewilding advocates believe that reintroducing extinct keystone species could help restore ecosystem functions that have been degraded since their disappearance. This argument is strongest for recently extinct species whose ecosystems still exist in some form.

Third, there’s what might be called the moral argument. If humans caused or contributed to an extinction, do we have an obligation to undo that harm if we can? Dire wolves likely went extinct due to a combination of climate change and human hunting pressure on their prey. If we can restore what was lost, perhaps we should.

Critics raise countervailing concerns. The resources devoted to de-extinction might be better spent on conserving species that still exist but are endangered. Resurrected species might not be able to survive in modern environments that differ from their original habitats. Introducing ancient predators could disrupt existing ecosystems in unpredictable ways. And the whole enterprise might distract from the harder work of preventing extinctions in the first place.

What Comes Next

If the dire wolf resurrection proves genuine, it opens a door that cannot be closed. Other companies and research groups are working on de-extinction projects, and success with one species will accelerate efforts with others. The mammoth, the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), the passenger pigeon, and the dodo are all targets of active research.

Regulation has not kept pace with the technology. Most jurisdictions have rules governing genetically modified organisms, endangered species, and animal welfare, but none specifically address resurrected extinct species. Questions about ownership, conservation status, and release into the wild remain legally ambiguous.

There’s also the question of what happens to the individual animals created through this process. Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi are presumably living in some form of captivity. They cannot be released into the wild without extensive study and regulatory approval. They are, in a sense, ambassadors for a species that no longer exists, living examples of what biotechnology can achieve.

The Bigger Picture

The dire wolf announcement, whether fully validated or not, signals that we have entered a new era in our relationship with extinction. For the first time in history, extinction may not be permanent. The species we have lost, at least some of them, might be recoverable.

This changes the moral calculus of conservation. If extinction isn’t forever, does that make it less tragic? Or does it place new obligations on us to preserve genetic material from endangered species, ensuring future generations can resurrect what we failed to save?

It also raises questions about what we value in nature. Is a genetically reconstructed dire wolf the same as a dire wolf that evolved naturally over millions of years? Does it matter if the animals lack the learned behaviors, social structures, and ecological relationships of their ancestors? A resurrected species is not quite the same as a species that never went extinct. But it may be closer than we ever expected to achieve.

The dire wolves named after Rome’s legendary founders and a fictional dragon queen are, in their own way, legendary. They represent something humans have dreamed about since we first understood that species could vanish forever: the power to reach back through time and undo the losses of the past. Whether that power is a gift or a danger depends on how wisely we use it.