You’ve probably heard that sleep is important for memory. The advice is everywhere: get a good night’s rest before an exam, sleep on it before making a decision, don’t pull all-nighters. But the mechanisms behind this advice have remained surprisingly murky. Scientists knew that sleep helped memories stick, but how it helped, and why some kinds of sleep seemed more important than others, stayed frustratingly unclear.

A new study has finally cracked part of this mystery, and the answer is stranger than anyone expected. Deep sleep, the slow-wave phases when your brain produces those characteristic rolling rhythms, doesn’t just strengthen memories. It physically relocates them. The brain structures responsible for recalling information actually shift during slow-wave sleep, moving memory processing from one region to a completely different one.

This discovery doesn’t just refine our understanding of sleep. It fundamentally reframes what we thought we knew about how memory works in the brain.

The Unexpected Finding

Researchers set out to investigate a well-established observation: people who get more slow-wave sleep tend to have better memory retention. The assumption was that this slow-wave sleep was somehow “strengthening” the same neural circuits that encoded the memories initially. The brain, according to this view, was essentially replaying and reinforcing existing patterns.

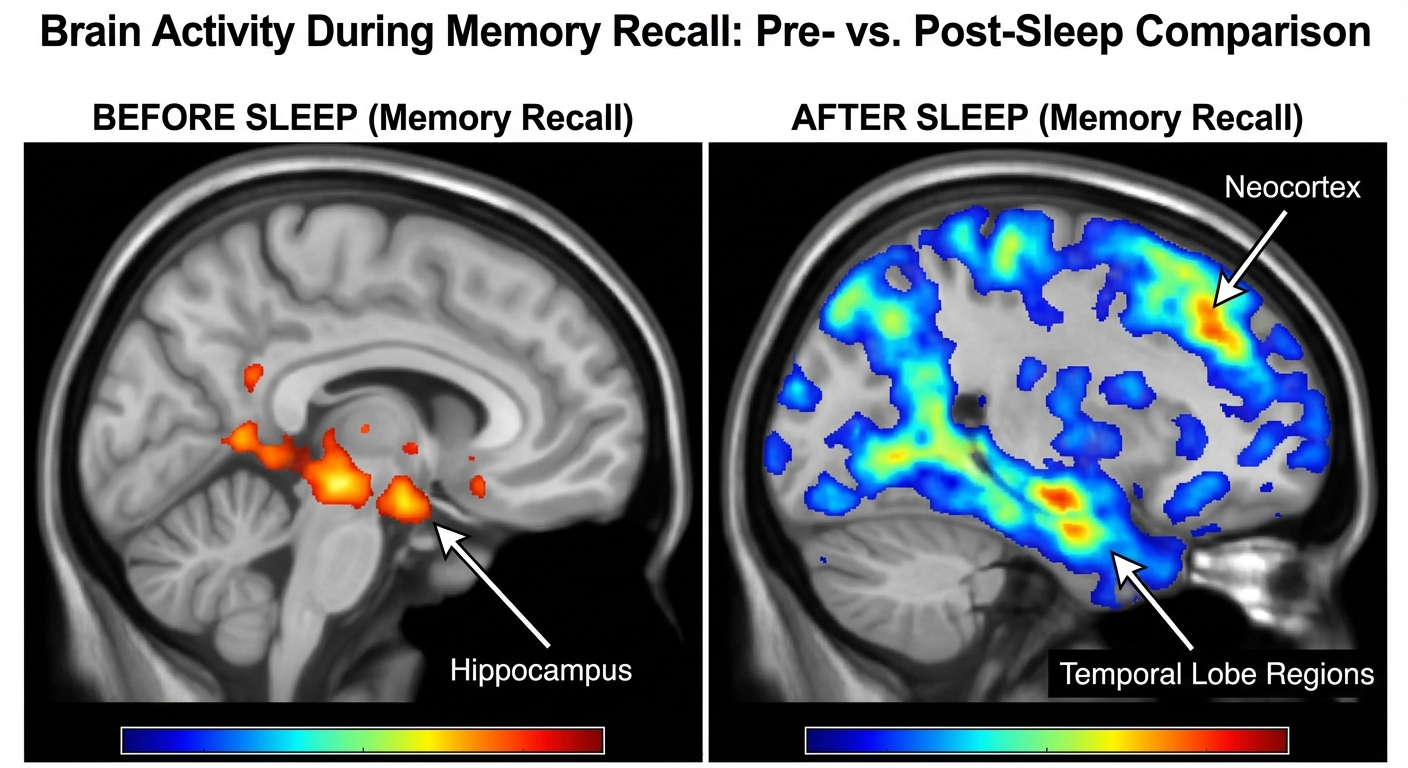

But when the team used functional brain imaging to track where memory recall activity occurred, they found something unexpected. Before sleep, recalling recently learned information activated one set of brain regions. After a night of sleep rich in slow-wave activity, the same recall task activated different regions entirely. The memories hadn’t just been consolidated. They had moved.

Specifically, memories that initially depended heavily on the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure deep in the brain that’s crucial for forming new memories, shifted toward the temporal lobe after adequate slow-wave sleep. The temporal lobe is associated with more stable, long-term memory storage. It’s as if the brain was filing documents away from a temporary inbox into a permanent archive.

The amount of shift correlated directly with the amount of slow-wave sleep. Participants who spent more time in deep sleep showed more complete relocation of memory processing. Those with fragmented or insufficient slow-wave sleep showed memories still partially stuck in the hippocampal “inbox,” more vulnerable to interference and decay.

Why Movement Matters

The distinction between where memories live has profound implications for how well they persist. The hippocampus is brilliant at rapidly encoding new information, but it has limited capacity and is vulnerable to interference from subsequent experiences. Each new memory you form competes for space with the old ones.

The temporal lobe, by contrast, stores memories in a more distributed, stable format. Memories here are less susceptible to being overwritten and can persist for years or decades. But the temporal lobe isn’t as good at rapid initial encoding. You need the hippocampus to catch the information first; then sleep helps transfer it to longer-term storage.

This two-stage system makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. You want to quickly capture potentially important information, like where you found food or encountered a predator, without having to decide in the moment whether it’s worth remembering forever. Later, during sleep when you’re safe, the brain can sort through the day’s experiences and move the important ones to permanent storage while letting the trivial ones fade.

The new research reveals that slow-wave sleep is literally when this sorting and filing happens. The slow oscillations characteristic of deep sleep aren’t just a byproduct of an idle brain. They’re the mechanism by which the brain coordinates the handoff between hippocampal and temporal memory systems.

The Rhythm of Transfer

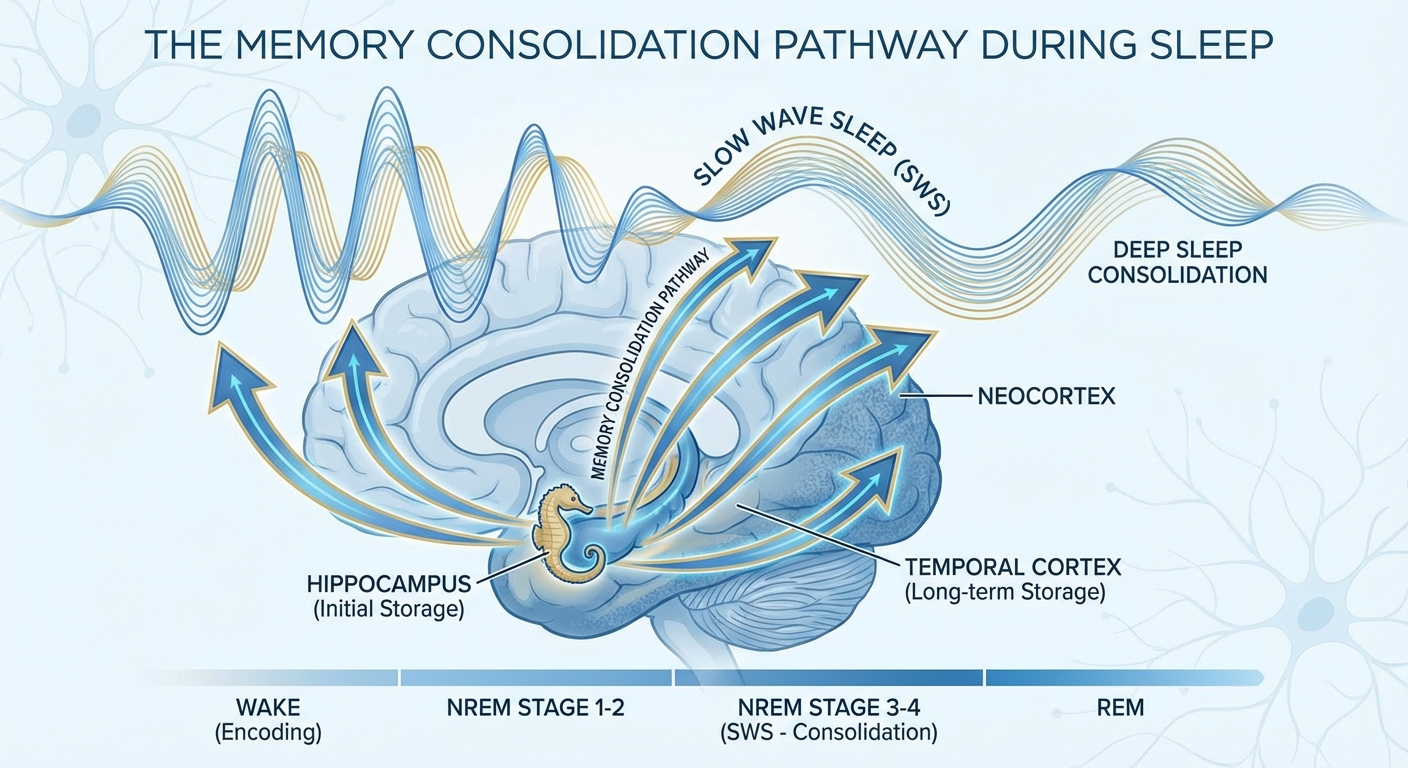

Understanding how slow waves facilitate memory transfer requires looking at what they actually are. During deep sleep, large populations of neurons fire in synchronized waves that sweep across the cortex about once per second. These aren’t random fluctuations; they’re coordinated rhythms that briefly alternate between states of high activity (the “up” state) and near silence (the “down” state).

Researchers now believe these synchronized oscillations create windows during which information can flow between brain regions. The hippocampus, which stores recent memories, generates its own faster rhythms called sharp-wave ripples. During slow-wave sleep, these hippocampal ripples become precisely coordinated with the cortical slow waves, creating moments when hippocampal memory traces can be “played” into the temporal lobe.

Think of it like a carefully choreographed file transfer. The hippocampus prepares packets of memory information and sends them during precisely timed windows when the temporal lobe is ready to receive them. The slow waves provide the clock that keeps both sides synchronized. Without adequate slow-wave sleep, the clock signal is weak, the windows are fewer, and the transfer remains incomplete.

This explains why memory consolidation isn’t just about total sleep time but specifically about time spent in slow-wave sleep. You can sleep for eight hours, but if your sleep architecture is disrupted, with insufficient slow-wave phases, your memories won’t transfer efficiently.

What This Means for Everyday Life

The practical implications extend beyond academic understanding. Consider why certain sleep disruptions are particularly harmful to memory. Alcohol, for instance, tends to suppress slow-wave sleep even when total sleep time seems adequate. This research suggests that the resulting memory problems aren’t just about being groggy; they reflect a genuine failure of memory transfer.

Sleep apnea, which causes repeated brief awakenings throughout the night, fragments sleep architecture and reduces slow-wave continuity. Patients often report memory problems that seemed out of proportion to their subjective sense of tiredness. The memory transfer mechanism provides a possible explanation: even if total sleep seems sufficient, the slow waves are too disrupted to coordinate effective hippocampal-temporal handoffs.

The research also illuminates why “sleeping on it” helps with learning. Studying right before sleep, rather than in the morning, takes advantage of the consolidation window. Memories encoded close to sleep are most likely to catch the next round of slow-wave transfer, potentially explaining why evening study sessions produce better long-term retention than morning ones.

For older adults, the findings carry particular significance. Slow-wave sleep naturally decreases with age, and this decline tracks closely with age-related memory difficulties. If reduced slow-wave sleep means incomplete memory transfer, interventions that enhance slow-wave activity might help preserve memory function in aging populations. Some researchers are already exploring acoustic stimulation techniques that can boost slow oscillations during sleep.

The Bigger Picture

The discovery that sleep physically relocates memories across brain regions is a reminder of how much the sleeping brain accomplishes. For most of history, sleep seemed like mere absence, a temporary shutdown while we recharged. We now know it’s an intensely active state during which the brain reorganizes itself in fundamental ways.

Memory consolidation is just one of sleep’s functions, but it’s increasingly clear that it’s essential. The hippocampus, constantly bombarded with new information during waking hours, would quickly overflow without the nightly export of memories to longer-term storage. Slow-wave sleep is the shipping department that keeps the whole operation running.

The broader lesson is that brain function depends on architecture in ways we’re only beginning to appreciate. Where in the brain something happens matters as much as what happens. A memory stored in the hippocampus isn’t the same as that memory stored in the temporal lobe, even if the information content is identical. The location determines stability, accessibility, and interaction with other memories.

Understanding these spatial dynamics opens new avenues for addressing memory disorders. If we can identify exactly how and when memories fail to transfer, we might be able to intervene. Techniques that enhance slow-wave sleep, improve synchronization between hippocampus and cortex, or directly support the transfer process could eventually become therapeutic tools.

For now, the immediate takeaway is simple: deep sleep isn’t optional. Those slow waves sweeping through your brain each night are physically reorganizing your memories, moving the important ones to safe storage while you dream. Skipping or disrupting that process doesn’t just leave you tired. It leaves your memories stranded, vulnerable, and incomplete.