The age of discovery never ended. While schoolchildren learn about naturalists cataloging new species in the 18th and 19th centuries, the rate of discovery today actually exceeds those historical peaks. Between 2015 and 2020, scientists documented an average of more than 16,000 new species per year, including over 10,000 animals, about 2,500 plants, and roughly 2,000 fungi. We are living in a golden age of species discovery, though it’s a race against extinction that gives the gold a tarnished sheen.

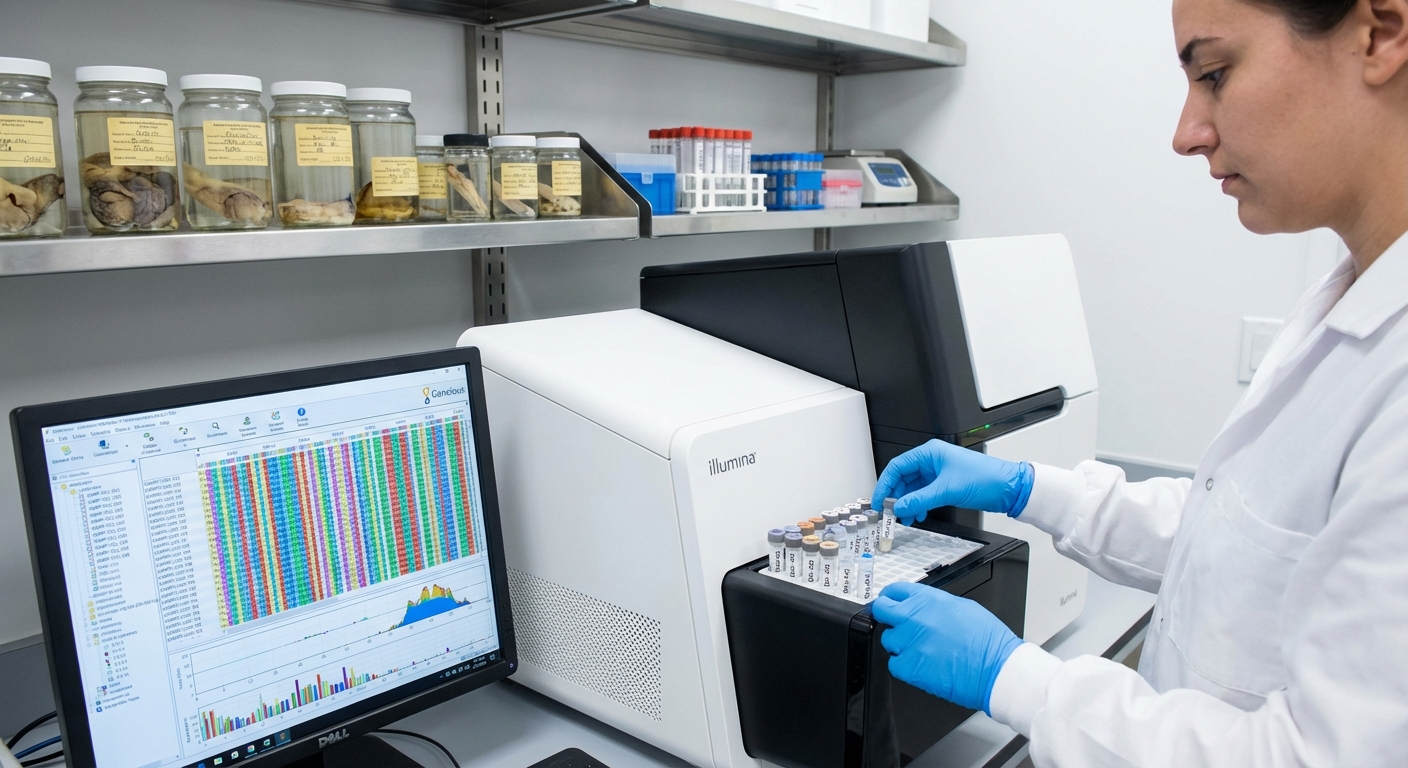

The acceleration comes from multiple factors: new technologies that reveal previously invisible organisms, exploration of habitats that were inaccessible to earlier researchers, and the systematic effort of thousands of taxonomists working across the globe. DNA sequencing has transformed the field, allowing scientists to distinguish species that look identical but are genetically distinct. Every year brings discoveries that surprise even specialists: new primates, new dolphins, new birds, creatures large enough that their prior obscurity seems impossible.

Yet this bounty of discovery happens against a backdrop of loss. Many species go extinct before they’re ever documented. Others are described from specimens collected decades ago that sat in museum collections waiting for a specialist to examine them. The golden age of discovery is also an age of urgency, a narrow window in which science races to catalog Earth’s biodiversity before it vanishes.

Why Now

Several factors have converged to make this era so productive for taxonomy. The most transformative is molecular genetics. Before DNA sequencing became cheap and routine, taxonomists relied on physical characteristics to identify and describe species. This worked well for organisms with distinctive features but failed for the many species that look nearly identical to their relatives.

DNA analysis revealed that what scientists thought was a single widespread species was often a complex of multiple species, each restricted to a smaller range. The concept of “cryptic species,” organisms that are genetically distinct but morphologically similar, has exploded our understanding of biodiversity. Entire groups that were thought to contain dozens of species now contain hundreds.

Technology has also made previously inaccessible habitats reachable. Deep-sea submersibles explore ocean trenches. Canopy walkways and climbing techniques allow thorough surveys of tropical rainforest treetops, where a disproportionate share of terrestrial biodiversity lives. Cave systems that once could only be glimpsed are now systematically explored. Each new habitat yields species found nowhere else.

The sheer number of people doing taxonomy has also increased. Citizen scientists contribute observations through platforms like iNaturalist, flagging unusual organisms for specialist attention. Researchers in biodiversity-rich countries who once had to send specimens abroad now have the training and facilities to describe species themselves. The taxonomic community is larger, more distributed, and better equipped than at any point in history.

What We’re Finding

The discoveries span the tree of life. Among vertebrates, new species of fish are described at a rate of about 300 per year, many from poorly explored river systems and deep-sea habitats. Amphibians yield 100 or more new species annually, particularly tiny frogs from tropical mountains that each evolved in isolation on their particular peak. Even mammals, the best-known group, produce around 25 new species per year, including primates, rodents, and bats that had been overlooked or misidentified.

Invertebrates represent the largest category by far. Insects alone account for thousands of new species annually, with beetles, flies, and wasps particularly well represented. Many are tiny, requiring microscopy to distinguish from relatives. Others are unexpectedly large, like the giant stick insects periodically discovered in tropical forests. The deep sea yields bizarre crustaceans and worms from habitats that had never been sampled before.

Plants and fungi add thousands more. Botanical exploration of remote regions continues to yield previously unknown trees, orchids, and herbaceous plants. Fungi have proven especially rich in undiscovered diversity, as DNA surveys reveal that most fungal species have never been formally described. The organisms decomposing a fallen log or forming mycorrhizal partnerships with forest trees often include species new to science.

Perhaps most remarkable are the discoveries of relatively large animals in well-studied regions. New species of beaked whales, forest elephants, and orangutans have been described in recent decades, creatures that seem too big to have escaped notice but whose distinctiveness was masked by similarity to known species.

The Race Against Extinction

The flood of discoveries occurs against a troubling backdrop. Extinction rates are estimated to be 100 to 1,000 times higher than the natural background rate. Habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, and invasive species are erasing biodiversity faster than at any time since the dinosaurs disappeared. Many of the species being discovered are already endangered.

Some species are known only from specimens collected long ago, their habitats since destroyed. They’re described from museum collections but may already be extinct in the wild, surviving only as preserved specimens and scientific names. Others are discovered in remnant habitats so small that their long-term survival is doubtful. The discovery and the conservation crisis arrive simultaneously.

Taxonomists face an impossible triage. With limited resources and time, they must decide which groups and regions to prioritize. Endemic species found nowhere else may warrant more urgent attention than widespread ones. Regions facing imminent habitat loss may take precedence over more stable areas. The choices are difficult, and no matter what’s prioritized, species will be lost before they’re ever known.

The concept of the “taxonomic impediment” captures this challenge. There are too few trained taxonomists, too little funding for the painstaking work of describing species, and too many organisms awaiting study. Museum collections contain millions of unexamined specimens. Field surveys generate samples faster than they can be processed. The golden age of discovery is also an age of overwhelming backlog.

The Bigger Picture

What does it mean to know what lives on Earth? The question might seem academic, but the answer has practical implications. Species we haven’t discovered may hold compounds useful for medicine. Ecological relationships we don’t understand may be critical for ecosystem services we depend on. The web of life is complex, and we’re still mapping its basic outlines.

More fundamentally, the effort to catalog Earth’s biodiversity is an attempt to understand our planet while we still can. The species alive today represent billions of years of evolution, a heritage that human activity is rapidly destroying. Documenting what exists, even if we can’t save all of it, creates a record of what the world contained before the Anthropocene reshaped it.

The golden age of species discovery is bittersweet. We’re finding more than ever, understanding more than ever, and losing more than ever, all at the same time. The race between discovery and extinction may be one we can’t win, but the effort itself has value. Every species described is a piece of knowledge rescued from oblivion, a name given to something that might otherwise vanish unrecorded. In the end, we may be left with records and specimens of a richer world than the one our descendants inherit.

Sources: International Institute for Species Exploration annual reports, Convention on Biological Diversity biodiversity assessments, taxonomic journal publication rates, museum collection surveys, extinction rate research.