In 2025, physicists at the University of British Columbia Okanagan published a paper making an extraordinary claim: they had mathematically demonstrated that the universe cannot be a computer simulation. The argument draws on one of the most profound results in 20th-century mathematics, Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, and applies it to the nature of physical reality. If correct, it settles one of the strangest questions to arise from the collision of physics and philosophy: Are we living in the Matrix?

The simulation hypothesis has haunted serious thinkers for decades. Nick Bostrom’s 2003 paper made a probabilistic case that if advanced civilizations can run simulations of conscious beings, and if many such civilizations exist, then most conscious beings probably exist in simulations rather than base reality. The argument seemed sound, and it was unclear how to refute it. The new work suggests an answer: the universe contains properties that no algorithm can replicate, making simulation not just unlikely but impossible.

The Simulation Question

The idea that reality might be a simulation is older than computers. Philosophers have long asked how we can be certain that our experiences correspond to an external world. Descartes imagined an evil demon deceiving him about everything; Plato described prisoners watching shadows on a cave wall. The simulation hypothesis is a modern version of these ancient puzzles.

What distinguishes the simulation hypothesis from earlier skeptical scenarios is that it is, in principle, testable. If we are in a simulation, there might be glitches, inconsistencies, or resource constraints that reveal the computational substrate. Physicists have proposed various tests, looking for discretization in space or time, searching for the kind of rounding errors that plague computer calculations.

But these tests have not found evidence of simulation, and absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. A sufficiently advanced simulation might hide its seams. The UBC Okanagan paper takes a different approach: instead of looking for flaws in the simulation, it argues that certain features of reality are mathematically incompatible with computation.

Gödel’s Incompleteness

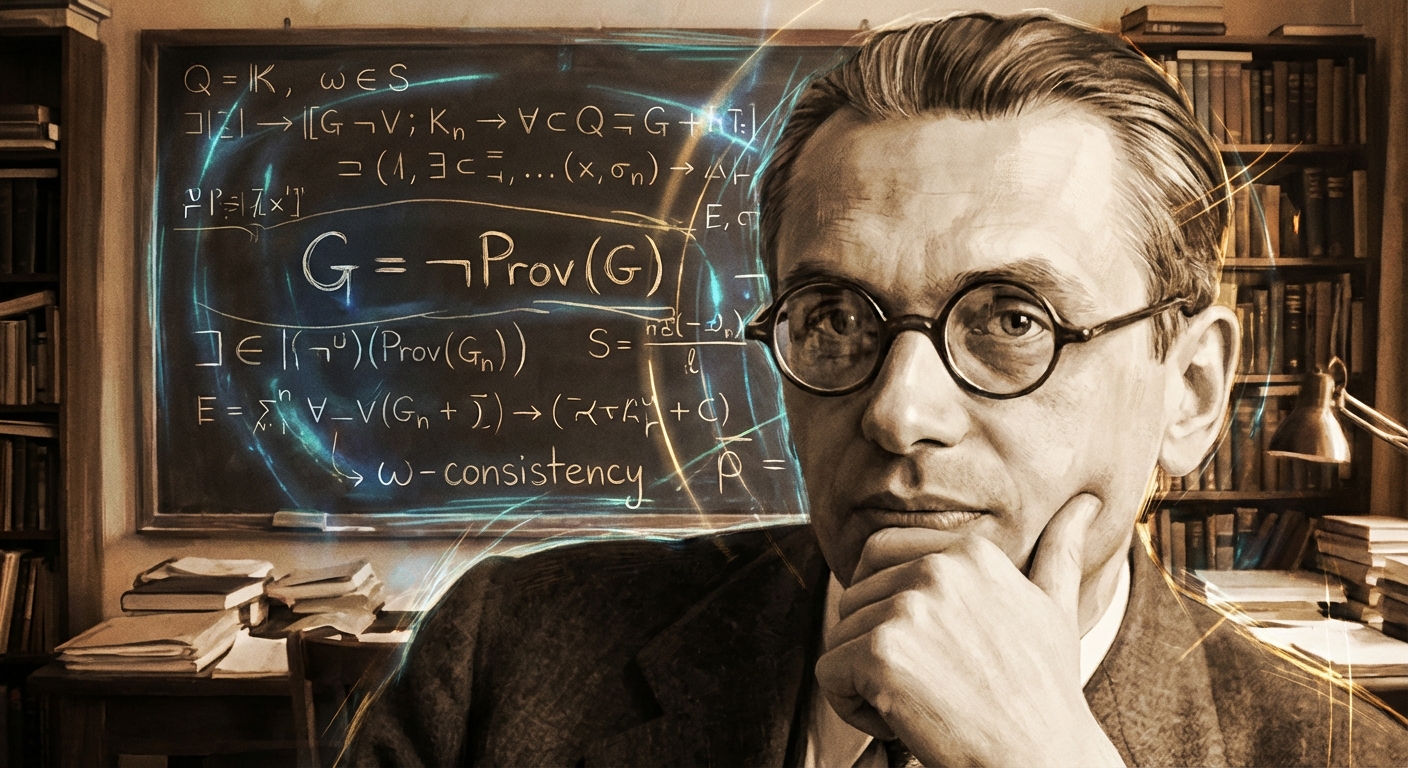

To understand the argument, you need to understand Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. In 1931, Kurt Gödel proved something that shocked the mathematical world: in any consistent formal system powerful enough to describe basic arithmetic, there are true statements that cannot be proved within the system. Mathematics, in other words, cannot be reduced to a complete set of rules.

This result shattered the dreams of mathematicians who hoped to place all of mathematics on a solid, mechanical foundation. It showed that mathematical truth exceeds what algorithms can capture. No matter how powerful your formal system, some truths will always lie beyond its reach.

The implications extend beyond mathematics. Alan Turing later showed that certain computational problems are undecidable: no algorithm can solve them for all cases. These undecidable problems are not rare curiosities but fundamental limits on what computation can achieve. Any system that runs on algorithms inherits these limits.

The Argument Against Simulation

The UBC Okanagan researchers argue that the physical universe contains undecidable elements. Specifically, they claim that understanding the universe fully requires what they call “non-algorithmic understanding,” a form of comprehension that cannot be captured by any computational process.

The argument is subtle. It does not claim that we cannot simulate most of what happens in the universe. We already do: weather models, molecular dynamics simulations, even crude models of galaxy formation run on computers every day. What the researchers argue is that capturing the full reality of the universe, including the properties that make it a coherent whole, exceeds what any algorithm can compute.

If this is correct, then the simulation hypothesis fails not because of practical limits on computing power but because of fundamental mathematical constraints. A simulation is an algorithm, and no algorithm can fully capture a reality that contains undecidable properties. We cannot be living in a simulation because simulations, by their nature, cannot do what the universe does.

Objections and Responses

Critics have raised several objections to this argument. One is that it assumes our understanding of computation is complete. Perhaps future mathematics will reveal new forms of computation that transcend current limits. The researchers respond that Gödelian incompleteness is not an artifact of current knowledge but a proven mathematical fact. Unless mathematics itself changes, the limits remain.

Another objection is that the argument conflates understanding the universe with simulating it. Perhaps a simulation does not need to capture everything, only enough to produce experiences indistinguishable from reality. The researchers counter that this weaker claim still requires the simulation to contain consciousness, and consciousness itself may have undecidable properties.

A third objection is philosophical: how do we know that our universe contains undecidable elements rather than merely appearing to? Perhaps the undecidability is itself simulated. The researchers acknowledge this as a hard problem but argue that the burden of proof shifts: anyone claiming the universe is simulated must explain how simulation can do what mathematics says algorithms cannot.

Implications for Physics and Philosophy

If the argument holds, the implications are significant. The simulation hypothesis has been a distraction for some physicists, a fascinating but ultimately unproductive speculation. Eliminating it would let researchers focus on understanding the actual universe rather than worrying whether that universe is real.

For philosophy, the result connects ancient questions about reality with modern mathematics. Descartes’ demon and Plato’s cave are not just thought experiments but can be engaged with using precise mathematical tools. The question of what reality is becomes, at least partly, a mathematical question.

The result also has implications for artificial intelligence. If understanding the universe requires non-algorithmic processes, then AI systems, which are fundamentally algorithmic, may face limits we have not fully appreciated. This does not mean AI cannot be powerful or useful, but it suggests that certain forms of understanding may be beyond its reach.

The Bigger Picture

The question of whether we live in a simulation may seem like science fiction, but it touches on deep issues. What is the relationship between mathematics and physical reality? What can we know about the universe, and what lies beyond knowledge? Are there limits to what any intelligence, natural or artificial, can understand?

The UBC Okanagan paper suggests that reality has features that transcend computation. This is not a mystical claim but a mathematical one, rooted in theorems proved nearly a century ago. If the researchers are right, the universe is not a program running on some cosmic computer. It is something stranger: a reality that includes truth that no algorithm can reach.

This should be humbling. We live in an era where computation seems omnipotent, where every problem seems solvable with enough data and processing power. The incompleteness theorems remind us that limits exist, that some truths will always exceed our systems. The universe, apparently, is one of those truths.

Whether or not you found the simulation hypothesis plausible, its potential refutation matters. It demonstrates that ancient philosophical questions can receive modern scientific answers. It shows that mathematics is not just a tool but a window into the nature of existence. And it reminds us that the universe, whatever else it is, remains a mystery deeper than any algorithm can fathom.