In 2013, a 61-year-old Texas man walked into an emergency room with a blood alcohol level of 0.37 percent, nearly five times the legal driving limit. He insisted he hadn’t been drinking. His wife, a nurse, confirmed it. The medical team didn’t believe either of them until they ran more tests and discovered something extraordinary: his gut was a brewery.

The man had auto-brewery syndrome, a condition so rare and counterintuitive that for decades doctors dismissed patients who described its symptoms. Now, thanks to new research identifying the exact microbes and metabolic pathways involved, we’re beginning to understand how the human body can ferment its own food into intoxicating levels of alcohol.

When Your Gut Becomes a Distillery

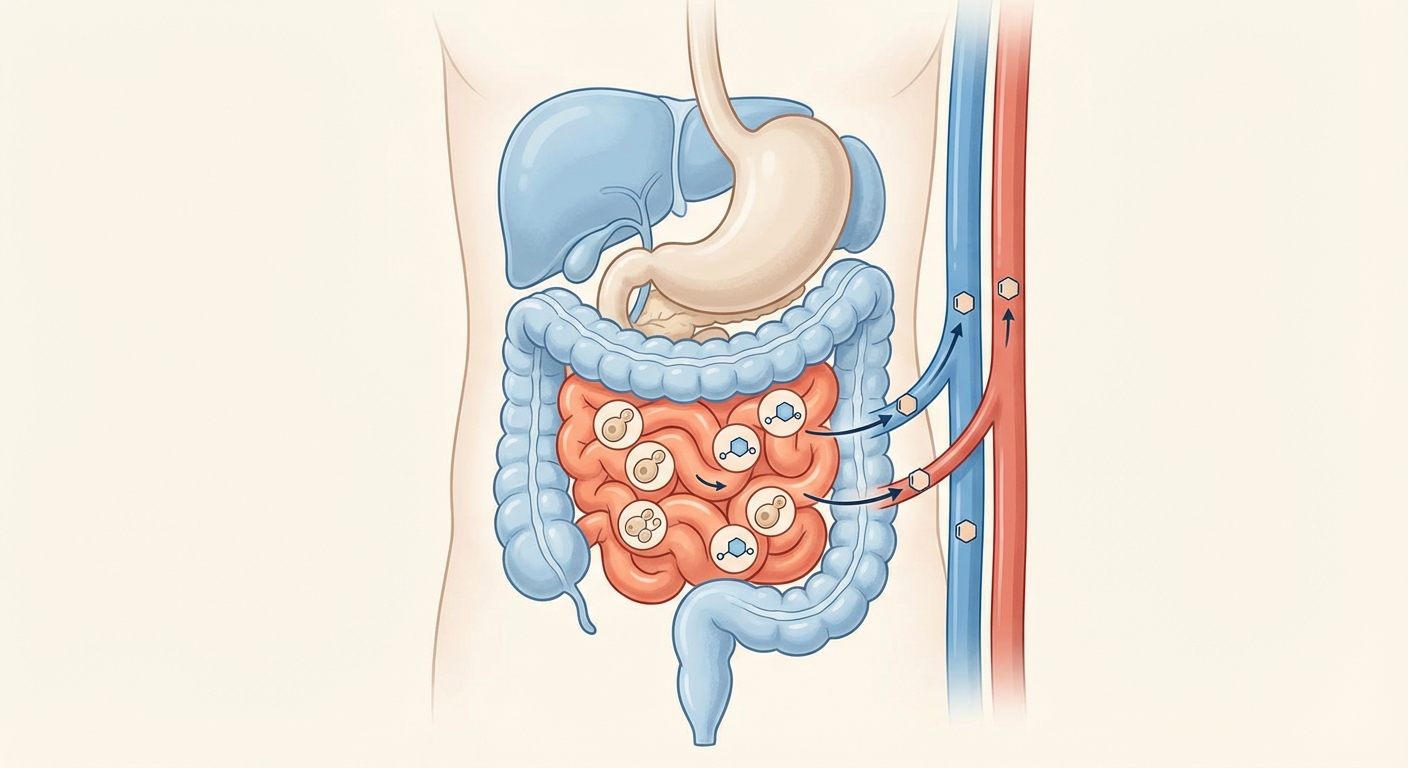

Auto-brewery syndrome (ABS), also called gut fermentation syndrome, occurs when fungi or bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract convert carbohydrates into ethanol. The process is identical to what happens in a beer vat or wine barrel: yeasts consume sugars and excrete alcohol as a metabolic byproduct. The difference is that this fermentation happens inside a living person.

The results can be devastating. Patients report sudden episodes of intoxication after eating bread, pasta, or anything high in carbohydrates. They experience slurred speech, impaired coordination, brain fog, and hangovers without ever touching alcohol. Some have been arrested for drunk driving, lost jobs, or had their children taken away by social services convinced they were closet alcoholics.

For years, these patients faced a medical establishment that largely didn’t believe their condition existed. A 2000 review in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology found only a handful of documented cases and suggested the syndrome was “extremely rare, if it exists at all.” Patients were told they were lying, in denial about a drinking problem, or suffering from psychiatric delusions.

The Microbes Behind the Mystery

Recent research has finally identified the specific organisms responsible. In most cases, the culprit is Candida species, particularly Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, and Candida krusei. These yeasts are normally present in small amounts in the human gut, kept in check by bacteria and the immune system. In auto-brewery patients, something has allowed them to proliferate.

A January 2026 study published in Nature Microbiology provided the most detailed picture yet of the syndrome’s mechanics. Researchers analyzed gut samples from 28 confirmed auto-brewery patients and found not just overgrowths of Candida but also unusual strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterococcus faecium. These bacteria, it turns out, can also produce significant quantities of ethanol.

What makes certain people vulnerable? The research points to a perfect storm of factors. Many patients had recently taken broad-spectrum antibiotics, which can wipe out the beneficial bacteria that normally suppress fungal growth. Others had diabetes or other conditions affecting blood sugar regulation, providing extra fuel for fermentation. Some had dietary habits extremely high in refined carbohydrates.

The study also found genetic factors at play. Several patients had variants in genes controlling immune responses to fungi, suggesting their bodies were less able to keep yeast populations in check. This helps explain why auto-brewery syndrome sometimes runs in families and why some people develop it while others with similar risk factors don’t.

A History of Disbelief

The medical literature’s skepticism toward auto-brewery syndrome reflects a broader tension in medicine between patient testimony and measurable evidence. The condition was first described in Japan in the 1950s, where researchers documented cases of people becoming intoxicated without drinking. But these reports were largely ignored in Western medicine.

Part of the skepticism stemmed from the implausibility of the mechanism. How could the gut produce enough alcohol to cause intoxication? Surely any ethanol produced would be metabolized by the liver before reaching significant blood concentrations. The assumption was reasonable but wrong.

The key insight came from understanding where in the gut fermentation occurs. When yeast overgrowth happens in the small intestine, ethanol is absorbed directly into the bloodstream before it can be processed by the liver’s first-pass metabolism. This is the same reason why alcohol consumed orally affects you faster than alcohol that might somehow bypass the stomach. Position matters.

Dr. Barbara Cordell, a Texas nurse practitioner who became one of the condition’s leading advocates after her husband was diagnosed, spent years documenting cases and fighting for medical recognition. Her work, along with gastroenterologist Dr. Justin McCarthy’s research at Richmond University Medical Center, helped transform auto-brewery syndrome from a curiosity into a recognized diagnosis.

The Fermentation Threshold

Not everyone with gut yeast produces problematic amounts of alcohol. In fact, virtually everyone produces some endogenous ethanol through normal digestive processes. The question is how much and how fast.

Healthy individuals typically have blood ethanol levels below 0.01 percent from endogenous production, far too low to cause any noticeable effect. Auto-brewery patients, by contrast, can reach levels of 0.2 percent or higher, well into the range of serious intoxication, from a single high-carbohydrate meal.

The difference appears to be both the quantity of fermenting organisms and their efficiency. The yeast strains found in auto-brewery patients are often more prolific ethanol producers than typical gut fungi. Some patients also have delayed gastric emptying, meaning food sits in the small intestine longer, providing more time for fermentation.

Interestingly, the syndrome seems to be self-reinforcing. Alcohol damages the gut lining and suppresses immune function, which allows even more yeast to colonize. Patients often describe a progressive worsening of symptoms over time, with smaller amounts of carbohydrates producing larger intoxication effects.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosing auto-brewery syndrome remains challenging. Blood alcohol tests only capture a moment in time, and episodes can be sporadic and unpredictable. The gold standard is a carbohydrate challenge test: the patient fasts overnight, eats a standardized high-carb meal under medical supervision, and has blood alcohol measured over several hours.

Even when the condition is confirmed, treatment requires patience. The standard approach combines antifungal medications like fluconazole or nystatin with a strict low-carbohydrate diet. Probiotics to restore healthy gut bacteria are often part of the regimen. Some patients require months of treatment before fermentation is brought under control.

Recurrence is common. Many patients describe managing the condition rather than curing it, remaining vigilant about carbohydrate intake and watching for early signs of yeast overgrowth. For some, the condition resolves completely after treatment; for others, it becomes a chronic reality requiring ongoing management.

The psychological toll extends beyond the physical symptoms. Patients describe the profound isolation of having a condition that sounds made up, of being accused of lying about something so strange that skepticism seems reasonable. The recent research validating the syndrome’s biological basis has brought relief to many who spent years doubting their own sanity.

The Bigger Picture

Auto-brewery syndrome sits at the intersection of several fascinating areas of modern biology. It’s a reminder that we are not individual organisms but ecosystems, hosting trillions of microbes whose metabolic activities profoundly influence our health. The gut microbiome can make vitamins, train our immune system, and apparently, under the right conditions, make alcohol.

The condition also illustrates the complex relationship between diet, medication, and microbial balance. Antibiotics, perhaps the most successful class of drugs in medical history, can have unintended consequences for the microbial communities we depend on. Auto-brewery syndrome is an extreme example of what can happen when that balance tips.

Perhaps most importantly, the history of auto-brewery syndrome teaches us about the limits of medical skepticism. For decades, patients who accurately described their symptoms were dismissed because those symptoms seemed impossible. The mechanism was eventually found, but only after researchers took the reports seriously enough to look for it.

How many other rare conditions remain undiscovered because they sound too strange to investigate? Auto-brewery syndrome suggests we should listen more carefully to patients whose experiences don’t fit our existing models. Sometimes the body really is doing something remarkable, even if we don’t yet understand how.