You know water. You’ve drunk it, swum in it, watched it freeze and boil. It’s the most familiar substance on Earth, so ordinary we rarely think about it. But take that same water and subject it to the conditions found deep inside giant planets, pressures millions of times greater than our atmosphere and temperatures hotter than the Sun’s surface, and something extraordinary happens. Water becomes superionic.

Superionic water is a state of matter that defies our everyday categories. It’s a solid, but its hydrogen atoms flow through it like a liquid. It’s ice, but it conducts electricity like a metal. First predicted theoretically in the 1980s and only confirmed experimentally in recent years, superionic water may be among the most abundant materials in the outer solar system, shaping the bizarre magnetic fields of Uranus and Neptune.

Water’s Hidden Identities

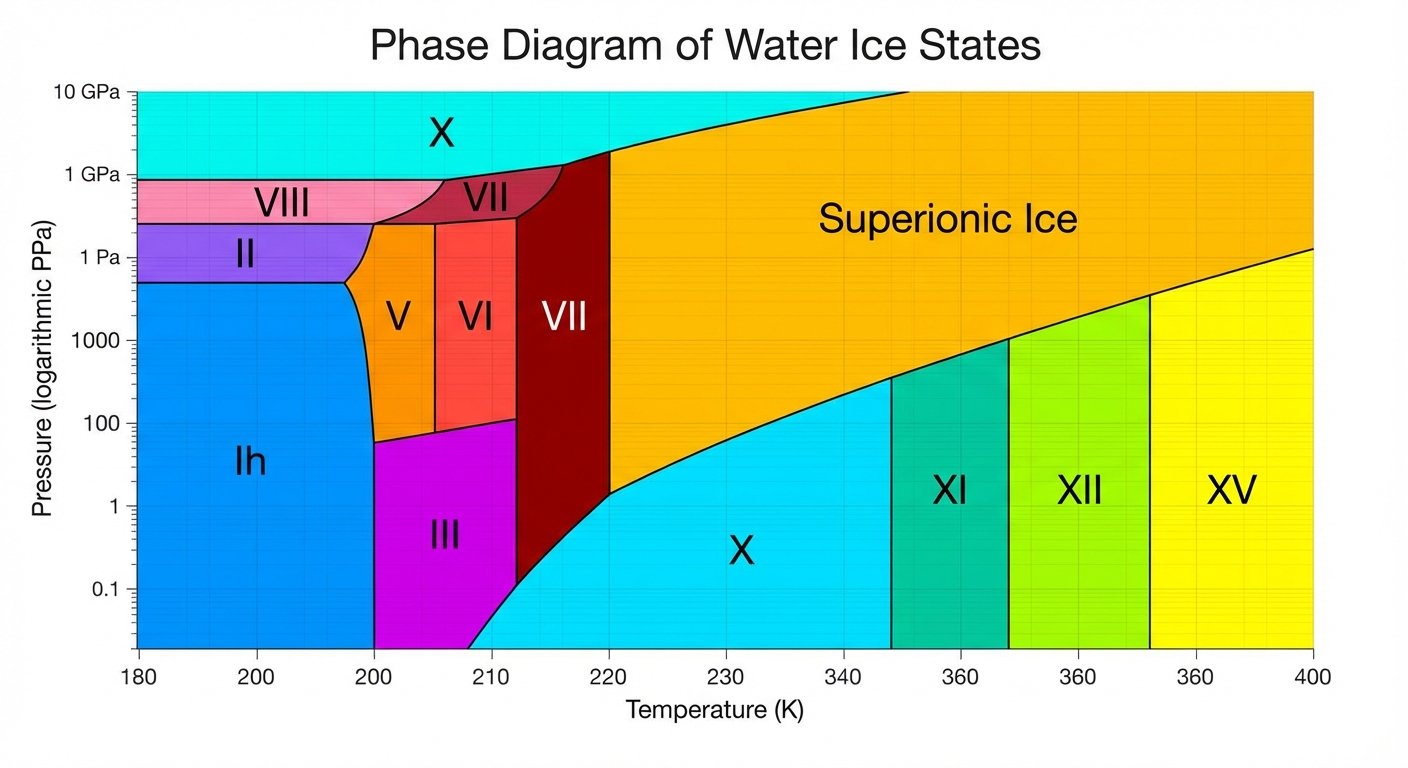

Before we can understand superionic water, we need to appreciate how strange water already is. Most substances have a single solid form: cool them down, and they freeze into a crystal. Water has at least eighteen known phases of ice, each with a different crystalline structure, depending on the temperature and pressure at which it forms.

The ice in your freezer is called ice Ih, the familiar hexagonal crystal that forms at atmospheric pressure. But compress ice Ih to higher pressures, and it transforms into denser forms: ice II, ice III, ice V, each with atoms packed in different arrangements. At extreme pressures, water enters realms where its behavior becomes genuinely alien.

The key to superionic water lies in what happens to the hydrogen and oxygen atoms under these conditions. In normal water and ice, oxygen and hydrogen atoms are bound together in H2O molecules. These molecules can arrange themselves in various crystal structures, but the basic unit remains intact. Under extreme pressure and heat, that changes.

The Superionic State

In superionic water, the extreme conditions partially dissociate the water molecules. Oxygen atoms lock into a rigid crystalline lattice, forming a solid framework. But the hydrogen atoms, stripped of their electrons, become free to move through this lattice like a fluid. The result is a material that is simultaneously solid and liquid, depending on which atoms you’re looking at.

This hybrid nature gives superionic water remarkable properties. Because the hydrogen ions (protons) can flow freely while the oxygen lattice remains fixed, the material conducts electricity efficiently. In this sense, it behaves like a metal, but it’s made entirely of water. The lattice provides structural rigidity while the mobile protons provide conductivity.

Creating superionic water in a laboratory is extraordinarily difficult. The conditions required, roughly 200 gigapascals of pressure and temperatures above 2,000 Kelvin, far exceed what most experimental setups can achieve. For context, 200 gigapascals is about two million times atmospheric pressure, equivalent to the weight of 200 jumbo jets concentrated on an area the size of a fingernail.

The breakthrough came from using powerful lasers to compress and heat tiny water samples for fractions of a second. In 2018, researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory achieved the first definitive experimental evidence of superionic water, confirming decades of theoretical predictions. Subsequent experiments have refined our understanding of its properties and the conditions under which it forms.

Inside the Ice Giants

Why does superionic water matter beyond the laboratory? The answer lies in the outer solar system, where two enigmatic planets have puzzled astronomers for decades.

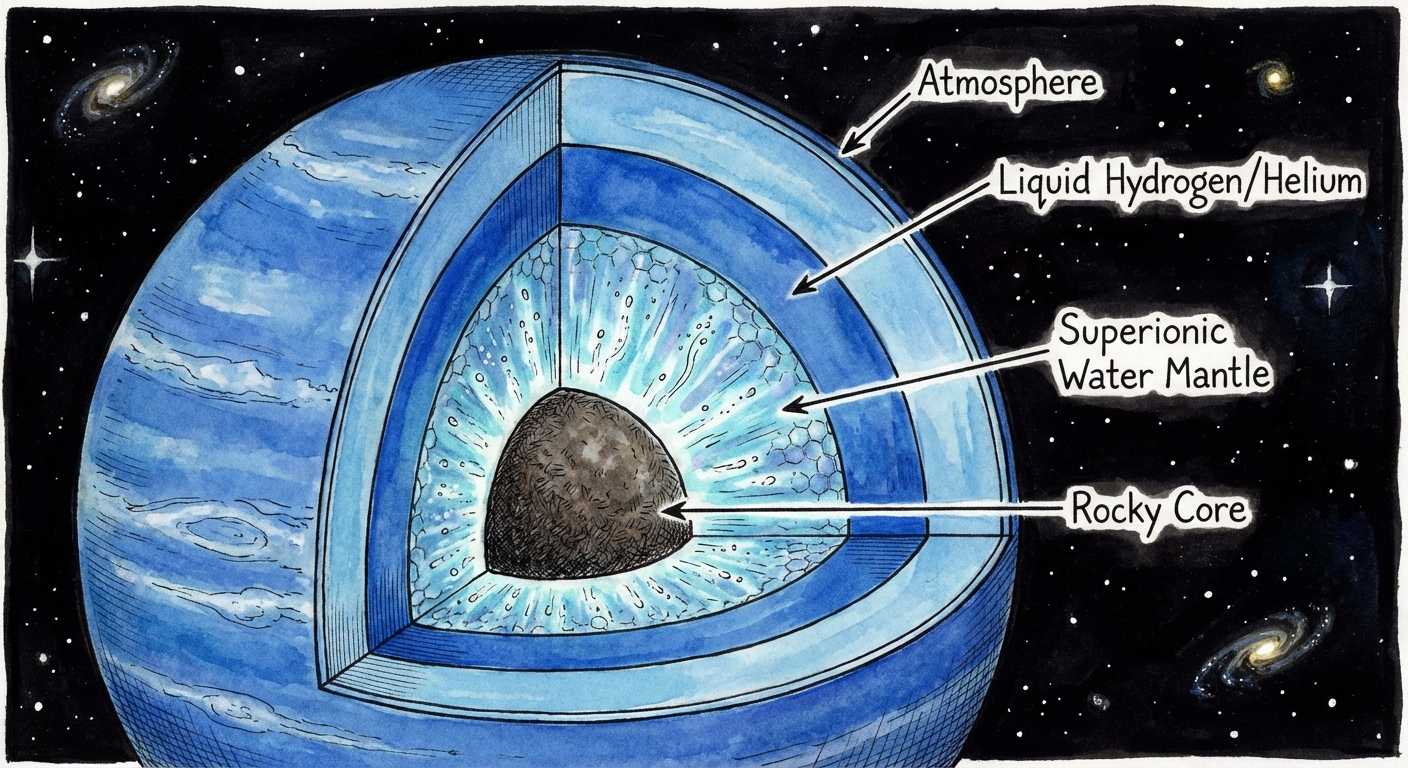

Uranus and Neptune are called ice giants, a term that’s somewhat misleading. They’re not made of frozen water like comets. Instead, their interiors contain vast quantities of water, ammonia, and methane under tremendous pressure and heat. The “ice” refers to these volatile compounds, not their physical state.

Both planets have magnetic fields that are deeply weird. Earth’s magnetic field is roughly aligned with its rotation axis, generated by convection in the liquid iron core. Uranus and Neptune have magnetic fields that are tilted dramatically from their rotation axes and offset from their centers. Neptune’s magnetic field is tilted 47 degrees; Uranus’s is tilted 59 degrees and doesn’t even pass through the planet’s center.

For years, planetary scientists struggled to explain these bizarre configurations. Standard models of magnetic field generation assume a conducting fluid moving in organized patterns. What could produce such asymmetric, off-center fields?

Superionic water offers a compelling answer. If the mantles of Uranus and Neptune contain thick layers of superionic ice, that material would be electrically conductive while remaining partially solid. The complex flows within such a layer, driven by the planets’ internal heat, could generate the lopsided magnetic fields we observe.

The Physics of Extreme Conditions

Understanding superionic water requires grappling with physics that operates far outside everyday experience. At the pressures inside ice giants, atoms are squeezed so close together that their electron clouds begin to overlap. Quantum mechanical effects dominate, and materials behave in ways that seem to contradict common sense.

The transition from normal ice to superionic ice is particularly interesting. As pressure increases, water molecules first arrange themselves into increasingly dense crystal structures. At around 50 gigapascals, ice enters the ice X phase, where hydrogen atoms sit exactly midway between oxygen atoms in a symmetric arrangement. Push pressure higher still, and the hydrogen atoms break free from their positions entirely, becoming mobile within the oxygen framework.

This liberation of hydrogen is driven by the extreme thermal energy. Even though the material is solid, temperatures inside ice giants can exceed 5,000 Kelvin. At these temperatures, hydrogen atoms have enough kinetic energy to overcome the forces holding them in fixed positions. They buzz through the crystal like a gas, following paths between the locked oxygen atoms.

Computer simulations have been essential for understanding these processes. Researchers use quantum mechanical calculations to model how atoms behave under conditions that cannot be sustained in laboratories. These simulations predicted superionic water’s existence long before it was confirmed experimentally and continue to reveal details about its structure and properties.

Beyond Water

Superionic behavior isn’t limited to water. Ammonia, methane, and other compounds abundant in ice giants may also enter superionic states under appropriate conditions. Understanding these materials is crucial for modeling what’s happening inside planets throughout the solar system and beyond.

The discovery of thousands of exoplanets, many of them ice giants or super-Earths with substantial water content, has made this research more urgent. If superionic water is common in planetary interiors, it may influence magnetic fields, heat transport, and evolution of worlds throughout the galaxy. What we learn about Uranus and Neptune has implications far beyond our solar system.

There’s also interest in whether superionic water might have practical applications. Materials that conduct electricity while remaining solid could have uses in energy storage or electronics. While creating superionic water on Earth requires conditions far beyond practical technology, understanding its properties might inspire new materials with similar characteristics achievable under ordinary conditions.

The Bigger Picture

Superionic water reminds us that the familiar can become alien under the right circumstances. Water, the substance we know best, transforms into something almost unrecognizable when pushed to extremes. A solid that flows, an insulator that conducts, ice that exists at thousands of degrees: these apparent contradictions reveal the limits of our everyday intuitions about matter.

The story also illustrates how theoretical predictions and experimental verification work together in science. Superionic water was predicted from fundamental physics decades before anyone could create it. The prediction drove increasingly sophisticated experiments until confirmation was achieved. Now, new predictions about its behavior inside planets await their own tests.

Most broadly, superionic water connects laboratory physics to cosmic scales. The same quantum mechanics that describes atoms in a laser-compressed sample explains the magnetic fields of distant planets. Understanding matter at extreme conditions helps us understand the universe, from the cores of ice giants to the interiors of exoplanets we’ll never visit.

Water will always be familiar. But its superionic form reminds us that familiarity is a matter of perspective. Under the right conditions, the most ordinary substance in the world becomes something extraordinary, a window into physics that operates far beyond our everyday experience yet shapes the cosmos we inhabit.