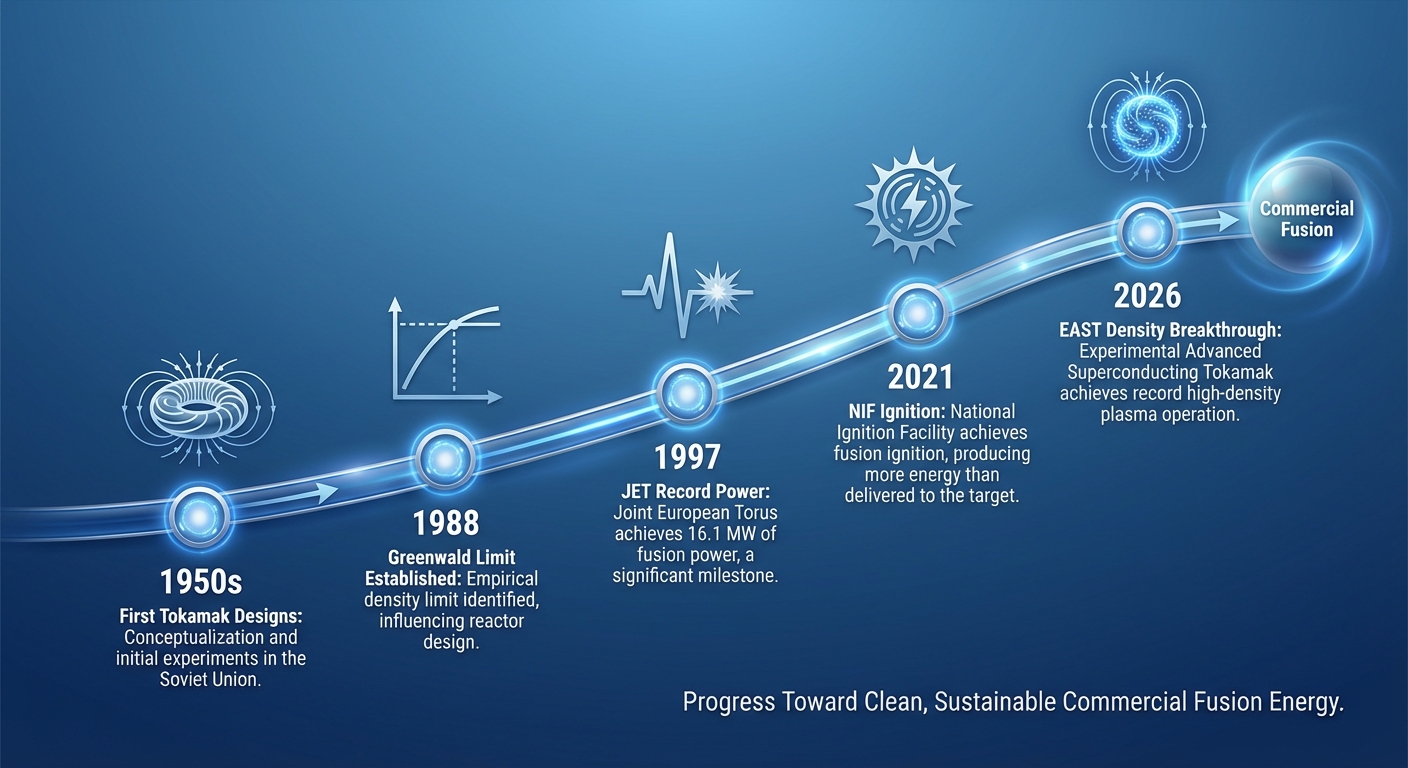

In 1988, physicist Martin Greenwald published a paper describing a frustrating limitation. No matter how hard fusion scientists tried, they couldn’t pack plasma above a certain density into their reactors. Push past this threshold, and the superheated gas would become unstable and crash into the reactor walls, ending the fusion attempt. For 35 years, this constraint, known as the Greenwald limit, has shaped every serious fusion reactor design on Earth. It was considered as fundamental to fusion engineering as the speed of light is to space travel.

Then, in January 2026, scientists operating China’s Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) announced they had done the impossible. They achieved stable plasma at 1.3 to 1.65 times the Greenwald limit, maintaining it long enough to confirm the result wasn’t a fluke. The technical details matter less than what this means: a rule that defined the boundaries of fusion physics for over three decades has been experimentally broken.

Understanding why this matters requires understanding what the Greenwald limit actually is, why it appeared so immutable, and how its breaking changes the path toward practical fusion power. This isn’t just an incremental improvement. It’s the kind of fundamental advance that makes previously impossible designs suddenly feasible.

What the Greenwald Limit Actually Means

Fusion reactors work by heating hydrogen isotopes to temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius, far hotter than the core of the sun. At these temperatures, matter exists as plasma, a state where electrons have been stripped from atomic nuclei. The goal is to make these nuclei collide with enough force to fuse together, releasing enormous energy in the process.

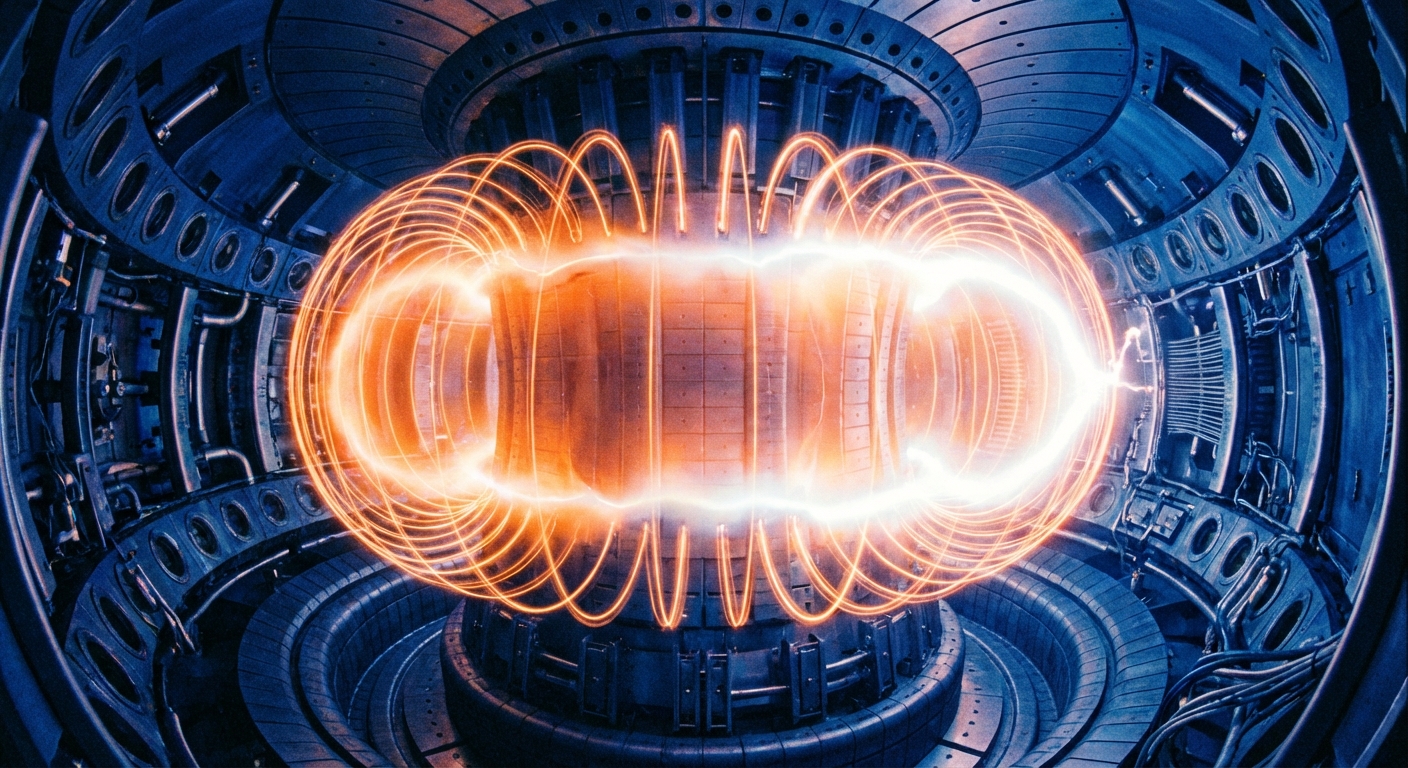

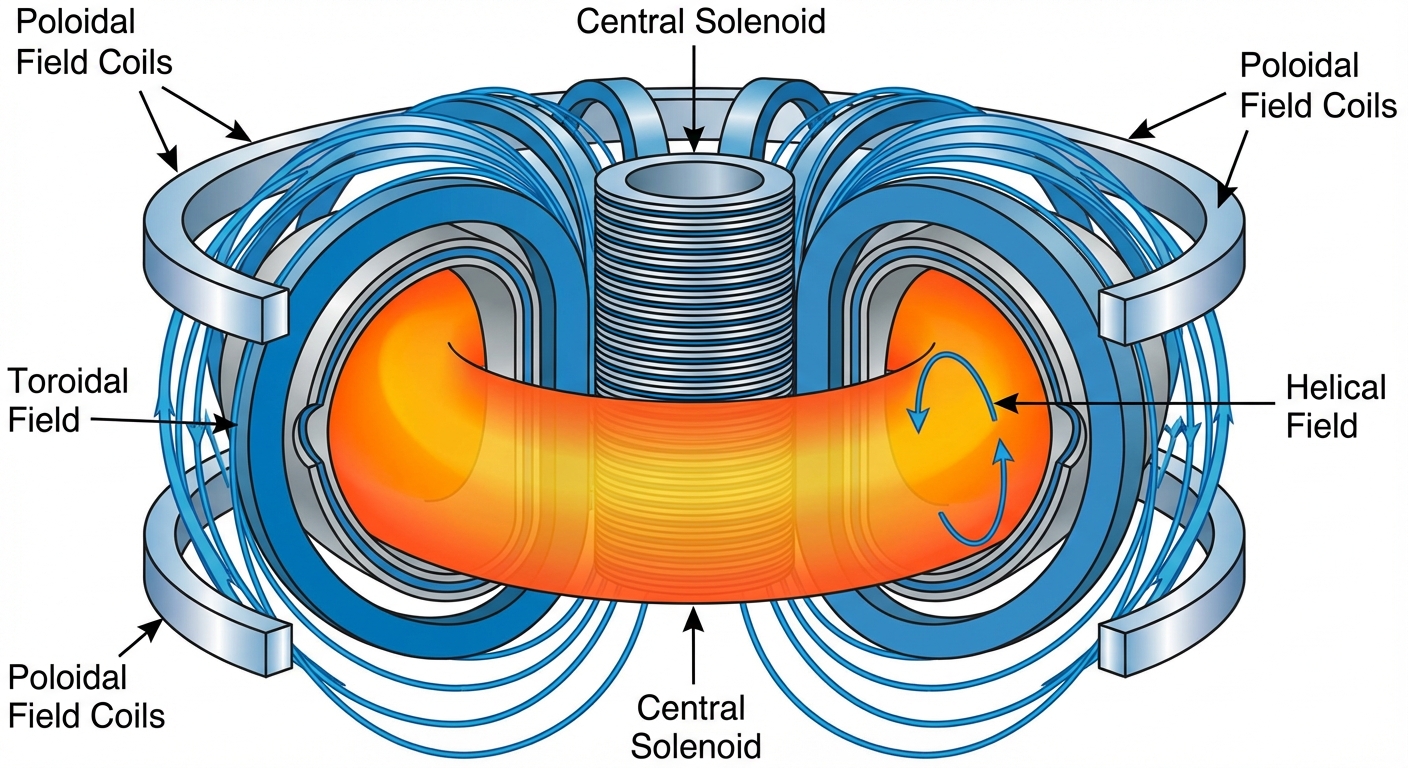

The challenge is containment. Nothing physical can touch plasma this hot without instantly vaporizing. So fusion scientists use magnetic fields to create an invisible bottle, suspending the plasma in the center of a donut-shaped chamber called a tokamak. The plasma floats there, never touching the walls, held in place by precisely tuned magnetic forces.

But here’s the problem Greenwald identified: you can’t just keep adding more fuel to the plasma. As plasma density increases, instabilities develop at the edge of the magnetic bottle. Small fluctuations grow into larger ones, eventually causing the plasma to touch the walls. When this happens, the plasma cools instantly, and the fusion reaction stops. This is called a disruption, and avoiding disruptions has been one of the central challenges of fusion engineering.

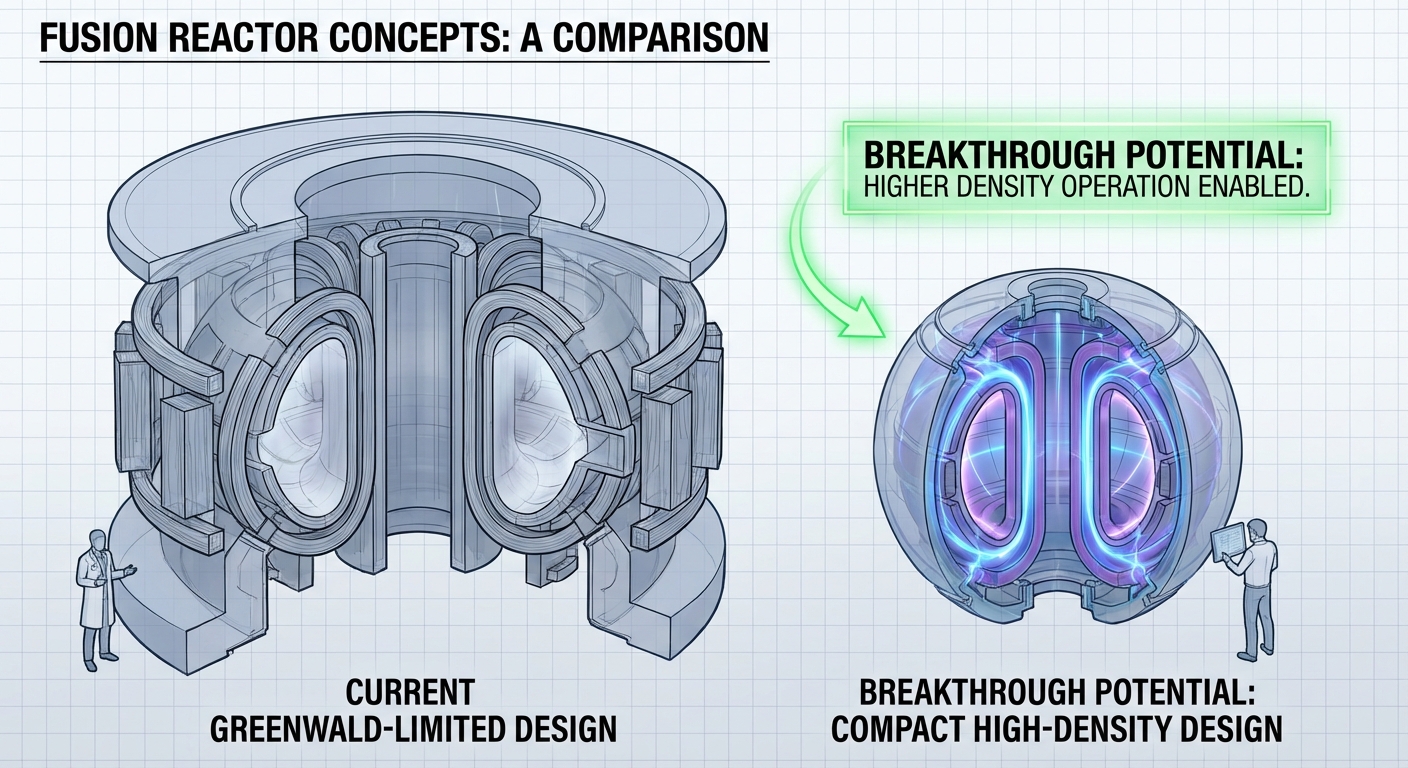

Greenwald found that the maximum density you could achieve followed a simple formula based on the size of the tokamak and the strength of the plasma current. Every tokamak built since has operated within this limit, designing around it as an immutable constraint. If you wanted more fuel in the plasma (which means more fusion reactions and more power output), you had to build a bigger reactor or run more current, both expensive propositions.

How They Broke the Limit

The EAST team didn’t break physics. They found a different operating regime that the original theory didn’t fully account for. The key was achieving what physicists call a “density-free” plasma state, where the relationship between density and instability behaves differently than Greenwald’s model predicted.

The technical approach involved sophisticated control of the plasma edge conditions. Most instabilities that cause disruptions originate at the boundary between the plasma and the surrounding vacuum. By precisely manipulating how energy flows at this boundary, the EAST team created conditions where higher density plasma remained stable.

This required coordinating multiple systems simultaneously: the magnetic field shaping, the heating systems, the fueling injectors, and the edge cooling. The plasma doesn’t naturally want to stay in this state; it requires active, real-time control to maintain. But maintain it they did, demonstrating that the Greenwald limit isn’t a fundamental law of nature but rather a description of how plasma behaves under certain conditions.

The distinction matters enormously. If the limit were truly fundamental, like the speed of light, there would be no engineering around it. But if it’s a consequence of specific operational choices, then different choices might avoid it entirely. The EAST results suggest the latter is true.

Why Density Matters for Fusion Power

Fusion power output scales roughly with the square of plasma density. Double the density, and you quadruple the potential power output from the same size reactor. This relationship is why the Greenwald limit has been such a frustrating constraint.

Consider the economics. Building bigger reactors to achieve more power is expensive. The ITER project in France, currently the world’s largest tokamak under construction, has a price tag exceeding $20 billion. Much of that cost comes from the sheer scale required to achieve commercially relevant power output while staying within the Greenwald limit. If future reactors could operate at higher density, they could potentially be smaller, cheaper, and easier to build.

There’s another consideration: stability. Higher density plasmas, when properly controlled, can actually be more stable than lower density ones. This seems counterintuitive, since density is what Greenwald said caused instabilities. But the EAST experiments suggest that in the right operating regime, the extra pressure from higher density helps the plasma hold its shape. It’s somewhat like how a fully inflated balloon is more stable than a partially deflated one.

The implications extend to reactor design itself. Current tokamaks spend enormous engineering effort trying to avoid disruptions, including emergency shutdown systems, reinforced walls, and complex control algorithms. If higher density operation is inherently more stable, these safety margins might be reduced, simplifying design and reducing cost further.

The Path from Laboratory to Power Plant

The EAST result is a proof of concept, not a commercial reactor. Significant work remains before this breakthrough translates into practical fusion power. But it opens pathways that were previously considered closed.

The first question is reproducibility. Can other tokamaks achieve similar results? The physics should be universal, but the specific control techniques may require adaptation for different reactor configurations. Expect to see fusion laboratories worldwide attempting to replicate and extend the EAST findings over the coming years.

The second question is duration. The EAST experiments achieved high density for long enough to confirm the phenomenon, but commercial reactors need to operate continuously for months or years. Maintaining the delicate edge conditions that enable high-density operation over such timescales presents engineering challenges not yet addressed.

The third question is integration. A working power plant needs not just stable plasma but also efficient ways to extract the heat, breed new fuel, and generate electricity. These systems must work together reliably. Adding a new operating regime to the plasma physics complicates an already complex integration challenge.

Still, the timeline for fusion has potentially shifted. Many fusion projections assumed the Greenwald limit as a fixed constraint. Reactor designs, cost estimates, and development roadmaps were built around it. Those assumptions now need revisiting. The EAST team hasn’t just achieved a new record; they’ve expanded the design space for all future fusion development.

The Bigger Picture

Fusion has been “30 years away” for so long that the phrase has become a joke among energy researchers. The history of fusion is littered with premature optimism, unexpected challenges, and revised timelines. The Greenwald limit was one of many obstacles that made commercial fusion seem perpetually distant.

What makes this breakthrough different is its nature. Some fusion advances are engineering achievements: better magnets, improved materials, more powerful heating systems. These are important but incremental. Breaking the Greenwald limit is more fundamental. It shows that a constraint everyone had accepted wasn’t actually a constraint at all.

The history of technology is full of such moments. For decades, engineers “knew” that heavier-than-air flight was impossible, that the sound barrier couldn’t be broken, that silicon transistors couldn’t shrink below certain sizes. In each case, the limit was real until someone found a way around it. Sometimes the solution was new physics; sometimes it was new engineering; sometimes it was just looking at the problem differently.

The Greenwald limit now joins this list. It wasn’t wrong, exactly. Under the conditions Greenwald studied, his relationship holds. But those conditions aren’t the only ones possible. The EAST team found different conditions where different rules apply. This is how fundamental advances happen: not by violating nature, but by discovering that nature is bigger than our previous understanding suggested.

For anyone who has watched fusion progress inch forward for decades, this moment has a different quality. It’s not a promise of future achievement but evidence of expanded possibility. The rules have changed, and with them, the game.

Sources: Nature scientific news 2026, Chinese Academy of Sciences EAST tokamak reports, Martin Greenwald original plasma density research (MIT), ITER project documentation, fusion physics review literature.