When the James Webb Space Telescope released its first deep-field images in July 2022, astronomers expected to be surprised. The telescope’s infrared vision was designed to see further into the universe, and thus further back in time, than any previous instrument. What they didn’t expect were the little red dots.

Scattered across JWST’s deep-field images were strange objects that didn’t fit any known category. They appeared point-like, suggesting they were very distant, but they were far brighter than expected for their redshift. Their red color was unusual, different from the red of normal distant galaxies. They seemed too bright, too red, and too common. For two years, these “little red dots” defied explanation.

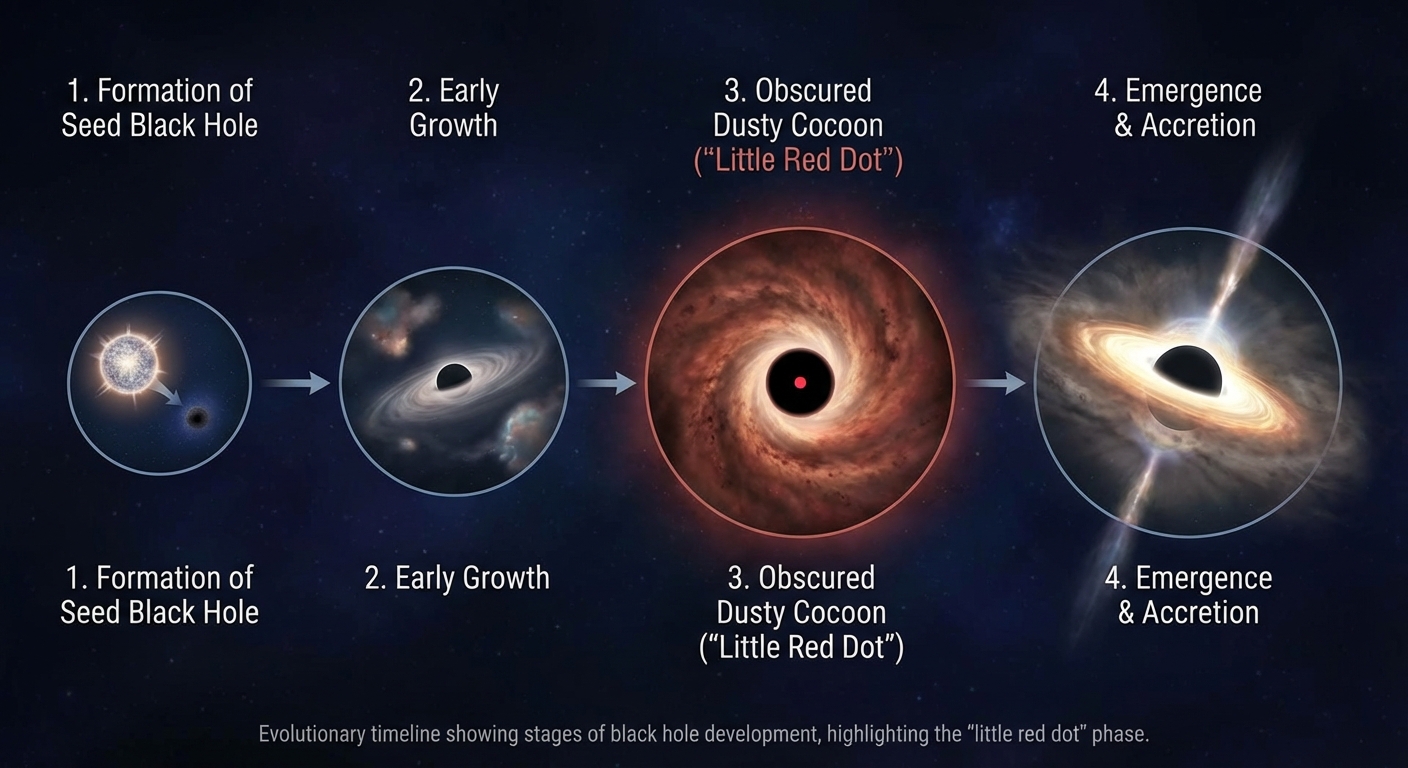

Now, new research has solved the mystery. The little red dots are young black holes, actively devouring matter in the hearts of early galaxies. But they’re hidden behind thick shrouds of gas and dust, their ferocious activity visible only through the cosmic dust that surrounds them. JWST has captured something extraordinary: black holes in their infancy, growing within cocoons that will eventually dissipate to reveal the blazing quasars they will become.

What the Little Red Dots Actually Are

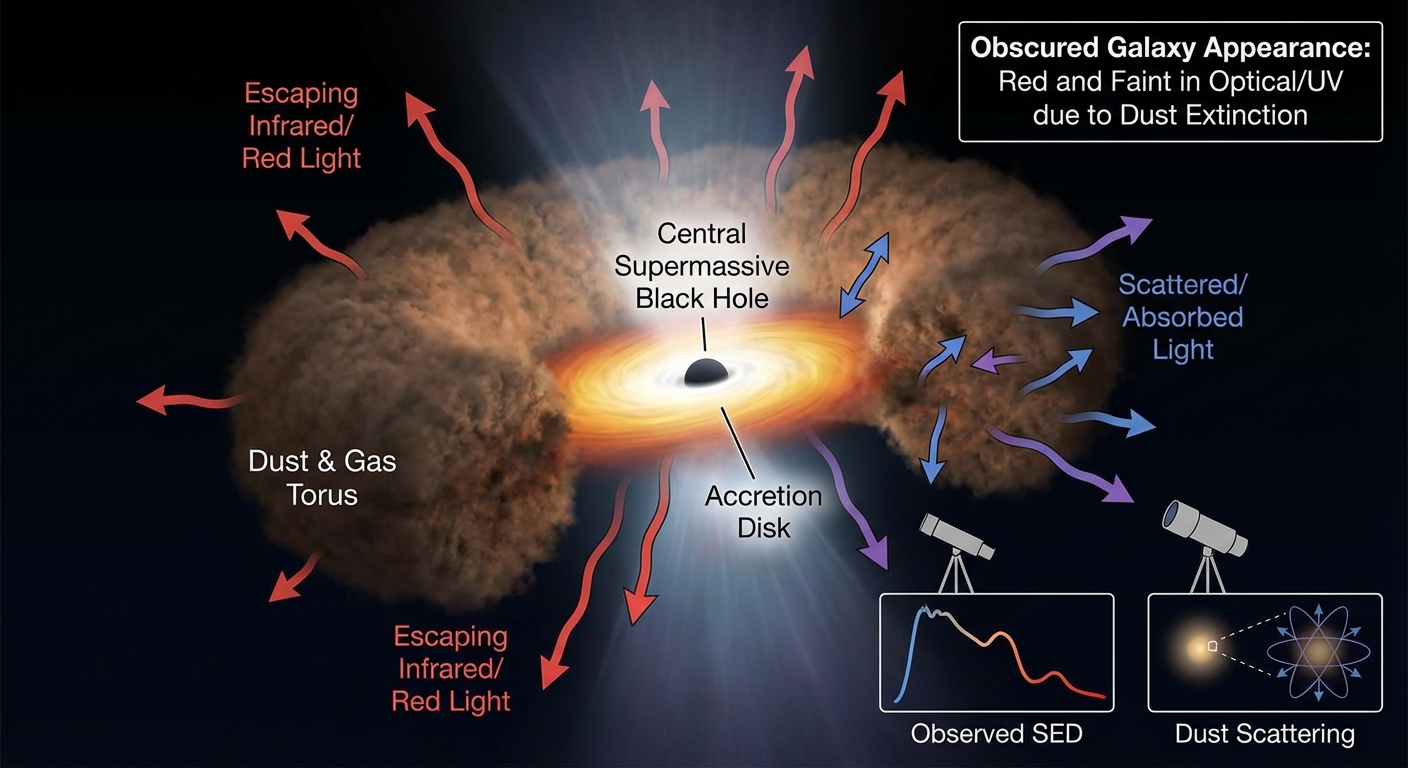

Black holes themselves are invisible; nothing escapes their gravitational grip, not even light. What astronomers see when they observe “black holes” is actually the material falling into them. This material, called an accretion disk, heats up as it spirals inward, glowing brighter than entire galaxies before crossing the event horizon and disappearing forever.

Normally, accreting black holes (called active galactic nuclei or AGN) are visible across the electromagnetic spectrum. Their accretion disks emit ultraviolet and X-ray light. When this light hits surrounding gas clouds, it excites the atoms, causing them to glow with characteristic emission lines. This combination of signatures makes AGN easy to identify, and astronomers have catalogued millions of them.

The little red dots don’t follow this pattern. They show extremely red colors, indicating their light has been heavily absorbed and scattered by dust. They lack the X-ray emission expected from visible AGN. Their emission lines are unusual, suggesting the light we see has passed through enormous amounts of material before reaching us. They appear to be AGN that are almost completely hidden behind dense cocoons of gas and dust.

This explains their redness. Dust absorbs and scatters short-wavelength light (blue and ultraviolet) more effectively than long-wavelength light (red and infrared). The intense radiation from the accreting black hole illuminates the surrounding dust, which then re-emits that energy as infrared radiation. The process is similar to how the setting sun appears red: light passing through a thick atmosphere loses its blue wavelengths to scattering, leaving only red behind.

Why This Matters for Understanding the Early Universe

The little red dots appear at high redshifts, meaning they existed when the universe was very young, typically less than a billion years old. Finding large black holes this early in cosmic history has always been a puzzle. Black holes grow by accreting matter, but this process takes time. How could massive black holes form so quickly after the Big Bang?

The little red dots may provide an answer. These obscured black holes are growing rapidly, hidden from view inside dusty cocoons. The cocoons don’t just hide the black holes; they feed them, providing a constant supply of gas to fuel their growth. Protected from external observation and fed by their surroundings, these black holes can grow much faster than their exposed counterparts.

This “hidden growth phase” may be a common stage in black hole development. Every massive black hole we see today, including the one at the center of our own Milky Way, may have passed through a similar obscured phase in its youth. The little red dots aren’t anomalies; they’re glimpses of a universal process that was previously invisible.

The research also reveals how common these objects are. Previous surveys, using optical and X-ray telescopes, missed the obscured population entirely. JWST’s infrared vision sees through the dust that blinded earlier instruments. The number of little red dots suggests that obscured black holes may be the dominant mode of early black hole growth, not an exceptional circumstance.

How Astronomers Solved the Mystery

Identifying what the little red dots actually are required combining JWST observations with data from other telescopes and sophisticated theoretical modeling. The key evidence came from spectroscopy, splitting the light from these objects into its component wavelengths to reveal its chemical and physical properties.

The spectra showed emission lines characteristic of gas heated by an intense radiation source, consistent with AGN. But the line ratios were unusual, suggesting the gas was extremely dense and heavily obscured. Some lines that should have been present were missing entirely, absorbed by intervening dust. The spectra told a story of enormous energy production happening behind a thick veil.

X-ray observations provided crucial negative evidence. Most AGN are bright X-ray sources because X-rays are produced close to the black hole and can penetrate moderate amounts of obscuration. The little red dots were X-ray faint, indicating either that the obscuration was extreme or that something unusual was happening with the X-ray production. Follow-up deep X-ray observations showed that the obscuration explanation was correct: these objects are surrounded by so much dust that even X-rays struggle to escape.

Theoretical models of how young galaxies evolve helped complete the picture. Computer simulations of the early universe predict that the first massive black holes should form in environments rich with gas and dust. These simulations produce objects that look remarkably like the little red dots: compact, extremely luminous, heavily obscured. The observations and theory are converging on the same answer.

What This Tells Us About Black Hole Origins

The origin of supermassive black holes remains one of astrophysics’ great mysteries. These objects contain millions to billions of solar masses, yet they appear in galaxies less than a billion years after the Big Bang. Getting that much mass into a black hole that quickly seems to require either impossibly rapid growth or starting from unusually massive seeds.

The little red dots favor the rapid growth explanation. If young black holes can grow in hidden cocoons, protected from the radiation feedback that normally limits accretion, they can put on mass much faster than exposed AGN. The cocoon doesn’t just hide the black hole; it enables its growth by containing the energy that would otherwise blow away the feeding material.

This has implications for the “seed mass” problem. If black holes can grow rapidly in obscured phases, they don’t need to start as massive as alternative theories suggest. Smaller seeds, perhaps the remnants of the first generation of stars, could grow to supermassive size through repeated obscured growth episodes. The little red dots may be showing us this process in action.

The connection between black hole growth and galaxy evolution also becomes clearer. The energy released by growing black holes can regulate star formation in their host galaxies, creating the observed correlations between black hole mass and galaxy properties. If much of this growth happens in obscured phases, we’ve been missing a crucial part of this co-evolution story. The little red dots reveal the hidden side of the black hole-galaxy relationship.

The Bigger Picture

The James Webb Space Telescope was built to see what previous telescopes couldn’t: the first galaxies, the first stars, the earliest chapters of cosmic history. The little red dots were an unexpected bonus, objects that no one predicted but that turned out to reveal something profound about how the universe’s most massive objects grow.

Every astronomical advance opens new questions. If obscured growth is common for young black holes, how does the transition from obscured to visible phases work? What triggers the clearing of the dusty cocoon? How do these objects relate to the more familiar quasars that illuminate the later universe? The little red dots have answered one mystery while posing several new ones.

The discovery also demonstrates the power of infrared astronomy. Dust, which blocks visible light, is transparent to infrared. Objects invisible to optical telescopes appear clearly in infrared images. The little red dots were always there, hiding in the early universe, but we needed the right kind of eyes to see them. JWST provided those eyes, and suddenly a hidden population emerged from the darkness.

Two years ago, the little red dots were a puzzle, anomalous specks on deep-field images that defied categorization. Today they’re recognized as young black holes caught in the act of growing, building mass inside dusty cocoons that hide their true nature. The universe’s heaviest objects, it turns out, begin their lives in disguise.

Sources: Nature astronomy news 2026, ScienceDaily James Webb Space Telescope research coverage, NASA JWST mission science updates, peer-reviewed papers on high-redshift AGN populations.