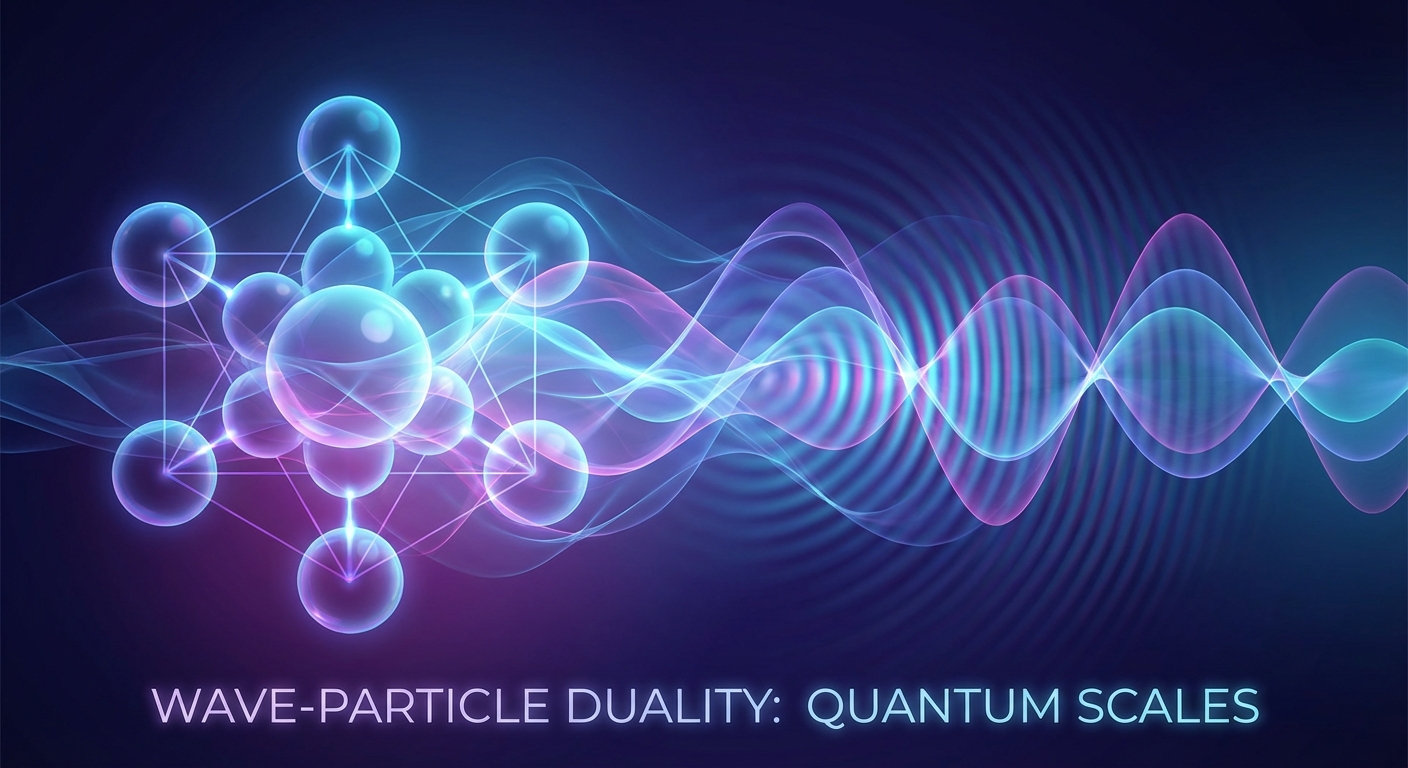

One of the strangest facts about the universe is that matter doesn’t behave the way common sense suggests. At small scales, particles like electrons act like waves, spreading out and interfering with themselves in ways that solid objects shouldn’t be able to do. This wave-particle duality has been experimentally confirmed for nearly a century, but it raises an uncomfortable question: where does the quantum weirdness end and normal reality begin?

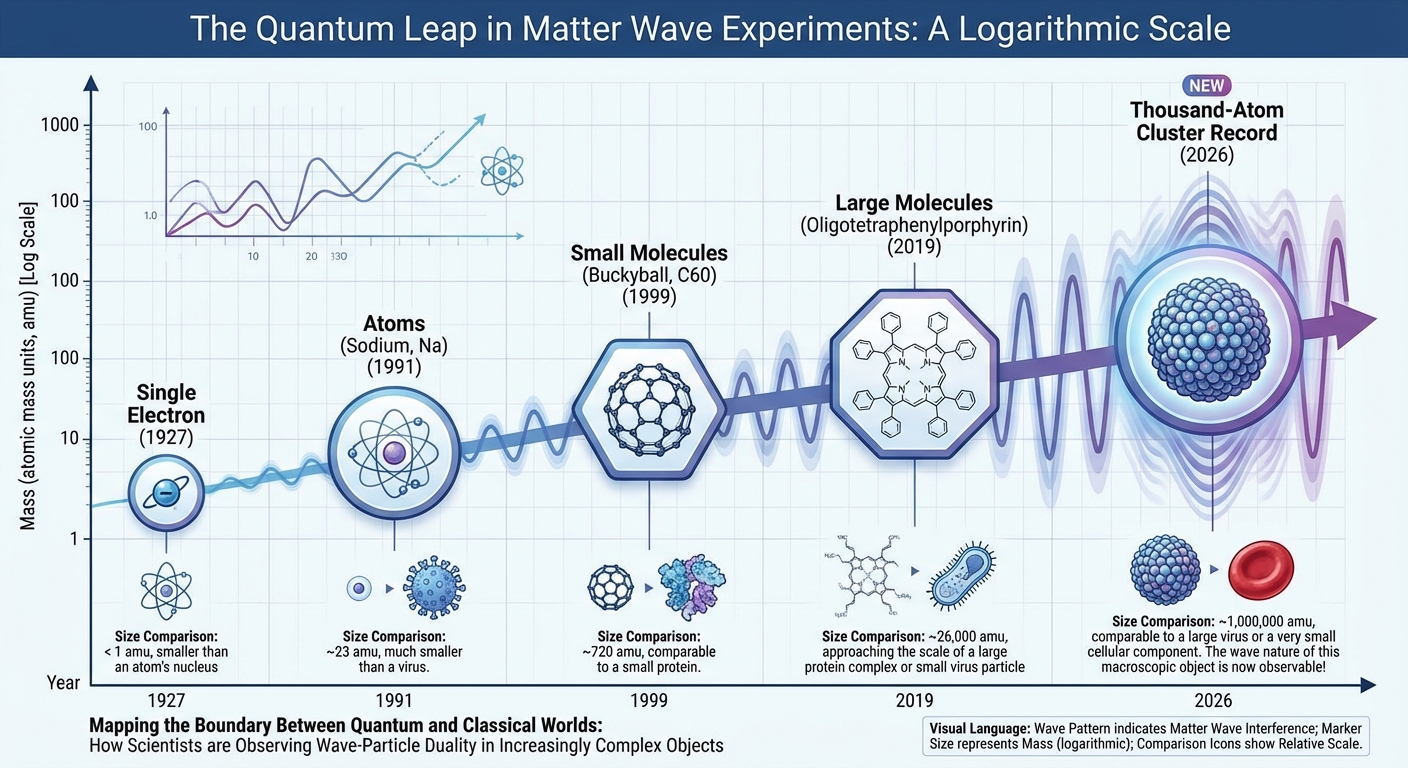

A new experiment has pushed that boundary further than ever before. Researchers have demonstrated wave-like behavior in a cluster containing thousands of atoms, the largest “quantum object” ever observed exhibiting this property. The cluster, though still microscopic by everyday standards, is massive by quantum physics standards. Its successful demonstration of wave behavior challenges intuitions about where quantum mechanics gives way to classical physics.

Understanding what this means requires understanding what matter waves actually are, why size matters, and what the experiment reveals about the nature of reality at its most fundamental level.

What Are Matter Waves?

In 1924, a French physicist named Louis de Broglie proposed something radical. If light, which had long been understood as a wave, could also behave like particles (photons), then perhaps the reverse was also true. Perhaps particles like electrons could also behave like waves. He derived a simple equation relating a particle’s wavelength to its momentum: the smaller the momentum, the longer the wavelength.

De Broglie’s hypothesis was confirmed just a few years later when physicists demonstrated that electrons passing through crystals produced interference patterns, exactly as waves would but particles shouldn’t. The electrons were somehow spreading out, interfering with themselves, and producing characteristic wave-like patterns. This wasn’t a peculiarity of electrons; subsequent experiments showed that protons, neutrons, atoms, and even molecules exhibited the same behavior.

The de Broglie wavelength depends inversely on mass and velocity. Heavier objects have shorter wavelengths; faster objects have shorter wavelengths. For everyday objects, the wavelength is so incredibly tiny that wave behavior is completely undetectable. A baseball traveling at 100 mph has a de Broglie wavelength smaller than the diameter of an atomic nucleus. For all practical purposes, baseballs are particles, not waves.

But as objects get smaller and colder (slower), their wavelengths get longer. Cool an atom to near absolute zero, and its de Broglie wavelength can stretch to micrometers, long enough to observe directly. This is the regime where quantum mechanics becomes visible, where matter stops behaving like the solid stuff we experience and starts revealing its wave nature.

The Challenge of Demonstrating Wave Behavior

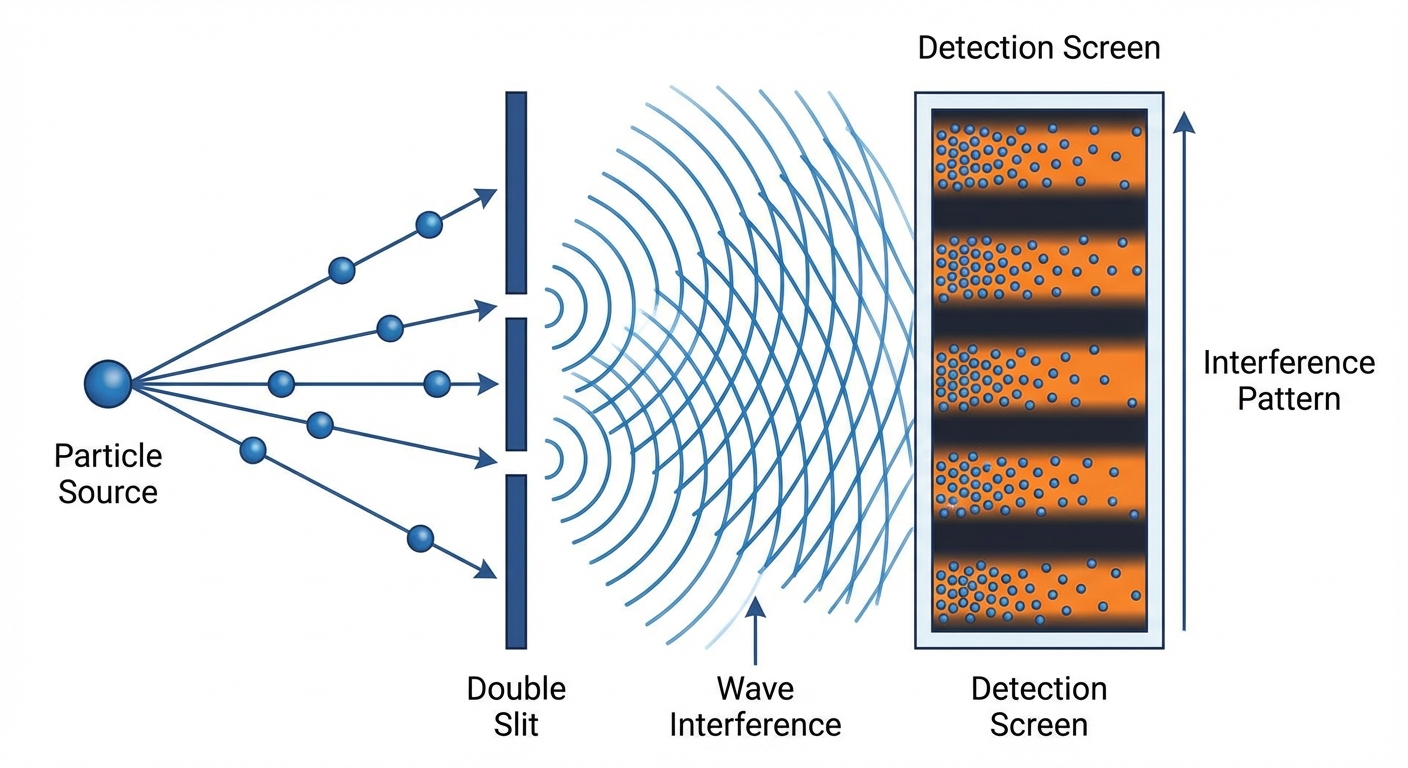

Demonstrating that something acts like a wave requires showing interference. When two waves meet, they can add together (constructive interference) or cancel out (destructive interference), creating characteristic patterns that particles simply can’t produce. The classic double-slit experiment sends particles through two openings; if they’re waves, they’ll interfere with themselves and create a striped pattern on a detector.

The difficulty is that wave behavior is fragile. Interactions with the environment, through collisions with gas molecules, absorption or emission of light, or any other physical process, cause the wave function to “collapse” into particle behavior. The larger an object, the more ways it can interact with its environment, and the faster this decoherence occurs. Maintaining wave-like behavior requires extraordinary isolation.

Temperature is critical. Atoms at room temperature are vibrating rapidly and constantly emitting and absorbing thermal radiation. This continuous interaction with the environment destroys quantum coherence almost instantly. To observe wave behavior, researchers must cool their atoms to temperatures measured in nanokelvins, billionths of a degree above absolute zero. At these temperatures, atoms move slowly enough that their de Broglie wavelengths become measurable and they interact with their environment slowly enough that coherence can persist.

Previous experiments had demonstrated wave behavior in single atoms, small molecules, and clusters of a few hundred atoms. Each increase in size represented a technical triumph, requiring better cooling, better isolation, and more sensitive detection. The new experiment pushed this boundary dramatically further.

The Breakthrough Experiment

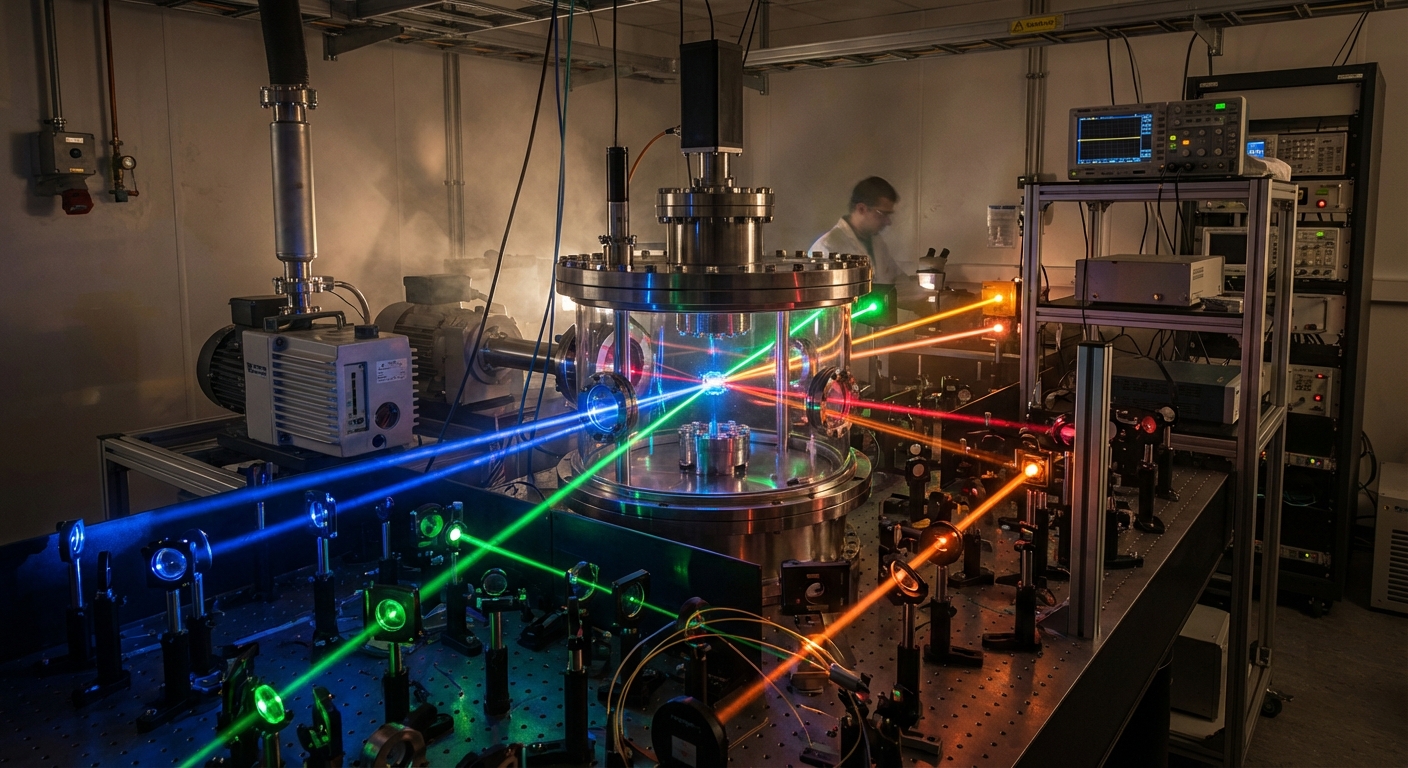

The experiment used sophisticated laser cooling and trapping techniques to prepare a cluster of atoms in an extremely cold, isolated state. The atoms were caught in a carefully configured electromagnetic trap that held them in place while lasers cooled them to near absolute zero. Once prepared, the trap was turned off, allowing the atoms to fall freely.

As the cluster fell, it passed through a series of laser pulses that acted like the slits in a double-slit experiment. The pulses split the atomic wave function into multiple paths, allowed the paths to evolve separately, and then recombined them. If the cluster maintained quantum coherence through this process, the recombined wave functions would interfere, producing patterns that could be detected.

The detection confirmed wave-like interference. The cluster of thousands of atoms, despite being far larger than any previous demonstration, still exhibited the characteristic pattern of wave interference. The atoms weren’t following individual particle trajectories; they were spreading out, taking multiple paths simultaneously, and interfering with themselves.

The technical achievement is remarkable. The experiment required maintaining quantum coherence in a system orders of magnitude larger than previous demonstrations. Every source of decoherence had to be identified and suppressed. The vacuum had to be extraordinarily good, eliminating stray gas molecules that could scatter the atoms. The laser pulses had to be precisely timed and calibrated. The detection had to be sensitive enough to resolve the interference pattern.

Why Size Matters

The philosophical interest of this result concerns where quantum mechanics ends and classical physics begins. Our everyday experience suggests that big things behave classically: baseballs follow trajectories, cars don’t tunnel through walls, cats are either alive or dead, not both. But quantum mechanics contains no built-in limit. Nothing in the equations says wave behavior should disappear above a certain size.

This creates what physicists call the “measurement problem” or the “macro-objectification problem.” If quantum mechanics is universal, why don’t we see quantum effects in everyday life? Various proposals have been offered: perhaps consciousness collapses wave functions, perhaps gravity causes decoherence, perhaps quantum mechanics simply doesn’t apply above certain scales. Each proposal is controversial, and none has been definitively confirmed or refuted.

Experiments pushing the quantum-classical boundary help constrain these proposals. If wave behavior can be demonstrated in larger and larger systems, proposals that predict quantum mechanics breaks down at small scales become less plausible. The new experiment pushes this constraint further, showing that systems far larger than previously demonstrated can still exhibit quantum effects under the right conditions.

This doesn’t mean we’ll see macroscopic quantum effects in everyday life. The conditions required to maintain coherence become increasingly difficult to achieve as size increases. The experiment succeeded because it created an artificial environment of extreme isolation and cold. Under normal conditions, decoherence would destroy the wave behavior almost instantly. The quantum world remains hidden not because quantum mechanics fails at large scales but because the environment is constantly “measuring” large objects, forcing them to behave classically.

The Bigger Picture

The demonstration that thousands of atoms can act as a single quantum wave represents both a technical achievement and a step toward understanding the fundamental nature of reality. Every experiment that pushes the quantum boundary provides data for testing theories about where quantum mechanics gives way to classical behavior.

More practically, understanding large-scale quantum coherence has implications for quantum computing and quantum sensing. Quantum computers rely on maintaining coherence in systems of qubits; understanding what enables or destroys coherence in larger systems informs the engineering of future quantum devices. Quantum sensors could potentially detect gravitational waves or dark matter by observing interference effects in atom clouds; larger clouds mean potentially more sensitive detectors.

The conceptual implications are equally significant. We live in a world that appears classical but is built from quantum components. The boundary between these regimes isn’t sharp; it emerges from the interaction between quantum systems and their environments. Each experiment probing this boundary teaches us something about how the solidity of everyday experience emerges from the wave-like fuzziness underneath.

A cluster of atoms, cooled to near absolute zero and isolated from the universe, briefly revealed its wave nature before rejoining the classical world. That brief revelation tells us something profound: the world we experience is not the world as it fundamentally is. The solidity of matter, the definiteness of position, the separation of object from object, these are all emergent properties, arising from quantum foundations that work by entirely different rules.

Sources: Science News January 2026, Nature physics news, de Broglie matter wave foundational papers, quantum decoherence research reviews, experimental matter wave demonstrations.