Hydrogen cyanide, chemical formula HCN, is one of the deadliest substances known. A few breaths of gaseous HCN can kill a human in minutes. It blocks cellular respiration, preventing cells from using oxygen, and has been used as a chemical weapon and means of execution. The idea that this notorious poison might be responsible for the origin of life sounds like a dark joke.

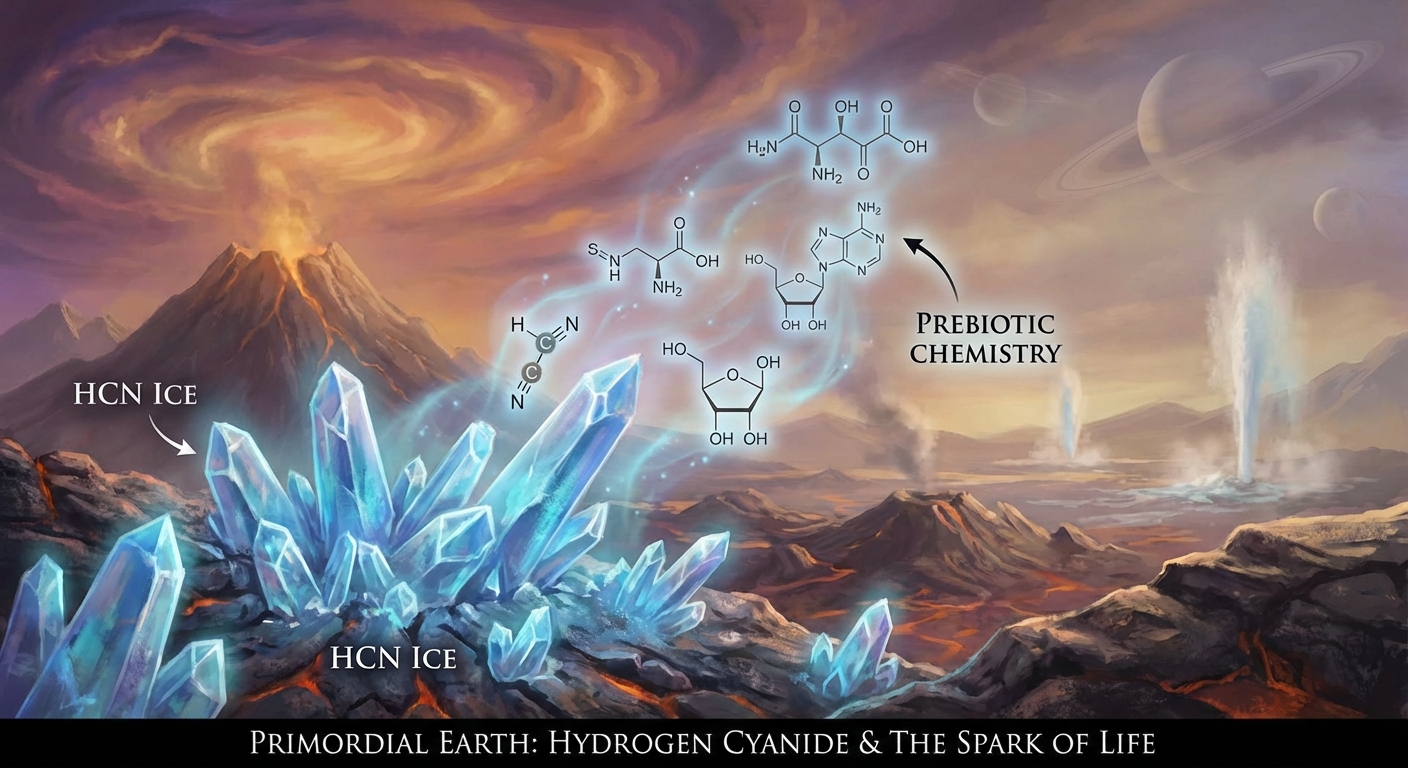

But chemistry has a peculiar sense of humor. Research published in early 2026 adds new evidence to a growing case that hydrogen cyanide wasn’t just present on early Earth but was actively necessary for life to begin. When frozen into ice crystals, HCN behaves in unexpected ways. Its crystal surfaces become highly reactive sites where simple molecules can assemble into complex organic compounds. The same substance that poisons living cells may have helped create them in the first place.

Understanding this paradox requires thinking about chemistry differently than we usually do. The chemistry of life and the chemistry of death aren’t always opposites. Sometimes they’re the same reactions happening in different contexts.

The Problem of Prebiotic Chemistry

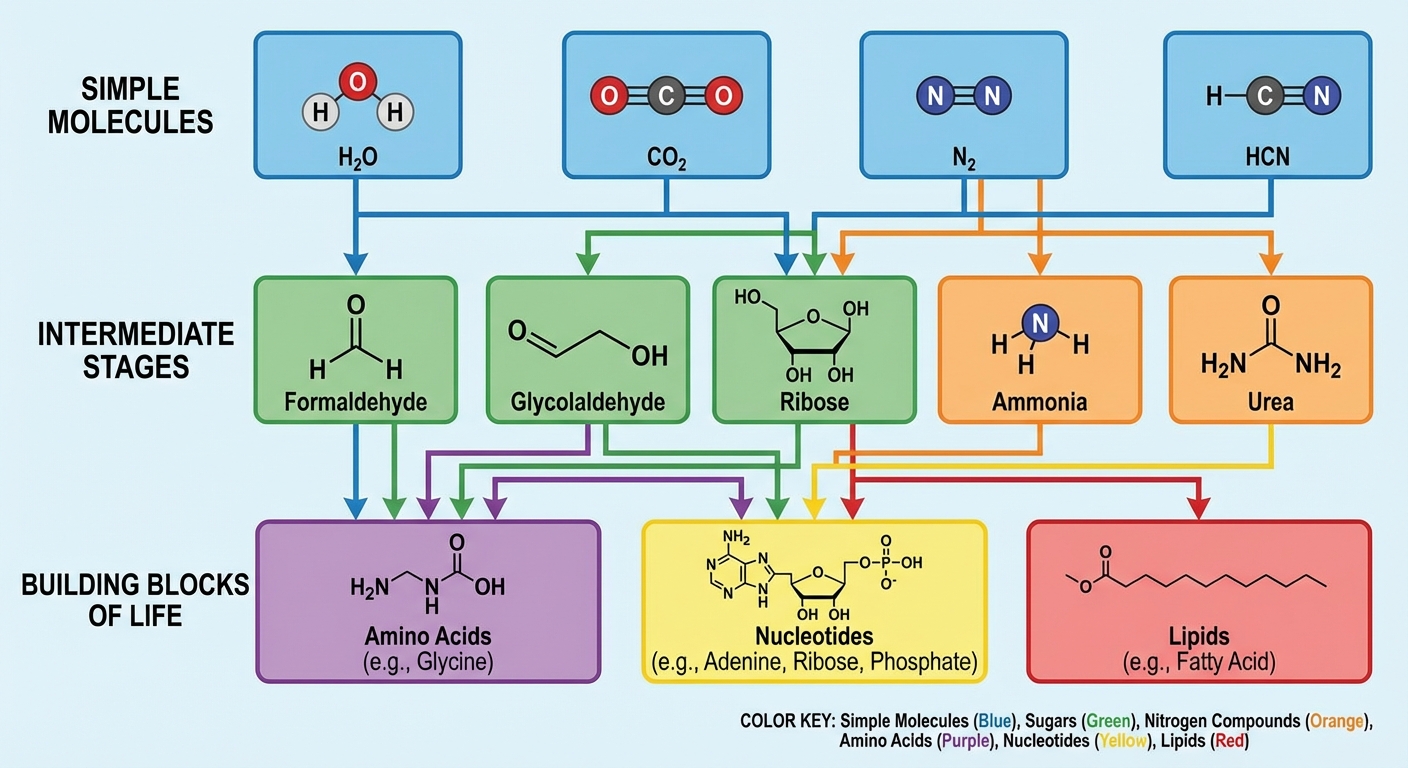

The origin of life requires solving a chemistry problem: how do you get from simple molecules like water, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen to the complex molecules that make up living cells? Proteins, DNA, RNA, and lipids are all built from smaller subunits: amino acids, nucleotides, fatty acids. Where did these subunits come from?

The classic answer, proposed by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey in the 1950s, involved lightning strikes in Earth’s early atmosphere. Their famous experiment produced amino acids from simple gases. But the Miller-Urey model has problems. The yields were low, the reactions non-specific, and subsequent research suggested Earth’s early atmosphere was different from what they assumed. Lightning alone doesn’t seem to provide the organized chemistry needed.

Prebiotic chemistry faces what researchers call the “concentration problem.” The reactions that build complex molecules require the reactants to be concentrated, not diluted in a vast ocean. But many proposed prebiotic reactions produce dilute solutions that then dissipate. How do you keep reactants together long enough for chemistry to happen?

Ice offers a solution. When water freezes, dissolved molecules get concentrated between ice crystals in tiny pockets of liquid. Paradoxically, freezing can actually accelerate chemical reactions by pushing reactants closer together. This “freeze concentration” effect has been demonstrated to enhance various prebiotic reactions. The cold early Earth wasn’t hostile to life’s emergence; it may have been necessary for it.

Why Hydrogen Cyanide Matters

Hydrogen cyanide enters this picture as a uniquely versatile building block. Despite being a simple molecule (one hydrogen, one carbon, one nitrogen, arranged in a line), HCN can undergo an extraordinary range of reactions. It can polymerize with itself, react with water to form amino acids, combine with aldehydes to build sugars, and serve as a nitrogen source for nucleotide synthesis. If you could only bring one molecule to a primordial chemistry set, HCN might be the best choice.

The new research focuses on what happens when HCN freezes. At very low temperatures, hydrogen cyanide forms crystals with unusual surface properties. The crystal lattice creates sites where molecules are held in specific orientations, positioned to react with each other in ways that wouldn’t happen in liquid solution. The crystal acts like a template, organizing reactants and lowering the energy barriers for specific reactions.

This surface catalysis turns out to be remarkably powerful. Reactions that would take impossibly long in solution occur on HCN ice surfaces at practical timescales. The crystals don’t just concentrate reactants; they actively drive reactions forward by providing an organized environment. It’s as if the ice crystals have a built-in recipe for making complex molecules.

The research demonstrated that frozen HCN can drive the formation of several important prebiotic molecules, including amino acid precursors and components of nucleotides. The reactions work even at extremely cold temperatures, relevant to environments far colder than Earth’s current surface. This means the chemistry could work on icy moons, comets, or the cold outer solar system as well as on frozen early Earth.

Where the Cyanide Came From

For hydrogen cyanide to play this role, early Earth needed a supply of it. This isn’t as problematic as it might seem. HCN is actually a common molecule in the universe, found in interstellar clouds, comet nuclei, and the atmospheres of some moons. Early Earth would have received significant HCN delivery from meteorites and comets.

Additional HCN would have formed from Earth’s own geology and atmosphere. Volcanic eruptions release various gases that can react to form cyanide compounds. Lightning in an atmosphere containing nitrogen and methane produces HCN. Impact events, when asteroids or comets struck the surface, generated shock chemistry that favored HCN formation. The early Earth may have had HCN concentrations far higher than anything found naturally today.

Once formed, HCN is relatively stable in cold environments but reactive under the right conditions. It can accumulate in frozen regions, building up concentrations that would be impossible in warmer liquid environments. Freeze-thaw cycles, common on early Earth with its variable climate, would repeatedly concentrate and release HCN, driving multiple rounds of prebiotic chemistry.

The research fits into a broader picture of early Earth as a chemically dynamic planet. Different environments, hot hydrothermal vents, frozen ponds, dry land surfaces, were each contributing different aspects of prebiotic chemistry. The molecules produced in one environment could be transported to another, where they would undergo further reactions. Life didn’t arise from a single process but from a network of interconnected chemical systems.

The Ice Crystal Template

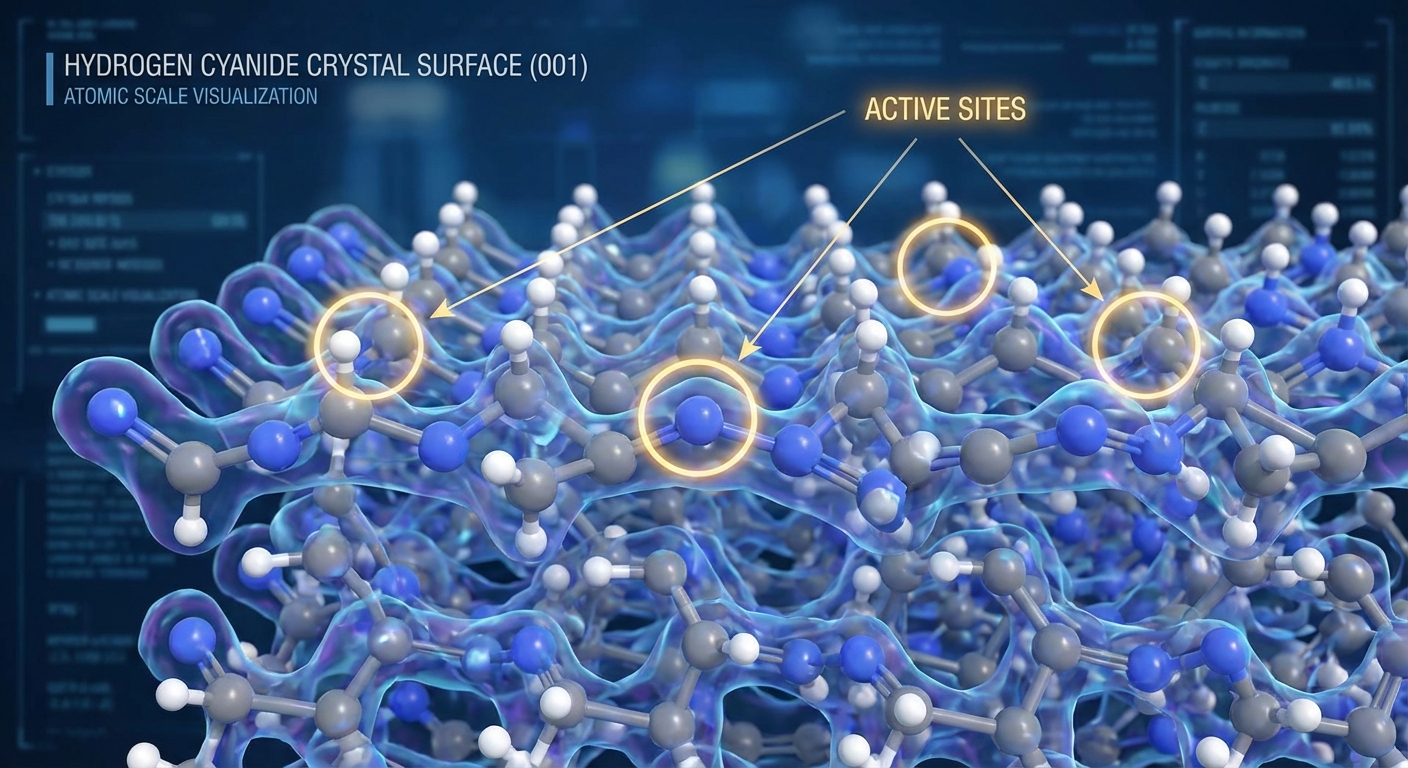

The most surprising finding concerns how HCN ice crystals organize chemistry. When HCN freezes, its molecules arrange themselves in a specific crystalline pattern. This pattern creates “active sites” on the crystal surface where additional molecules can bind and react. The crystal essentially becomes a solid-state catalyst, lowering energy barriers for reactions that would otherwise be extremely slow.

The geometry of the crystal surface matters. HCN crystals have specific facets with different arrangements of molecules. Some facets are more reactive than others, preferentially catalyzing particular types of reactions. This selectivity is crucial: random chemistry produces random products, but selective chemistry can build up specific molecules that are useful for life.

This template effect helps explain one of prebiotic chemistry’s persistent puzzles: chirality. Biological molecules often come in “left-handed” and “right-handed” versions (mirror images of each other), but life uses only one handedness. Random chemistry would produce equal mixtures of both. Crystal surfaces, with their specific geometries, can selectively favor one handedness over another. The origin of biological chirality might trace back to asymmetries in primordial ice crystals.

The research also shows that HCN crystal chemistry works at temperatures as low as -78°C (the temperature of dry ice) and possibly even colder. This extreme cold tolerance opens up possibilities beyond Earth. Icy moons like Europa and Enceladus, comets in the outer solar system, and even interstellar ice grains could host similar chemistry. The building blocks of life might be assembling in cold environments throughout the cosmos.

The Bigger Picture

The hydrogen cyanide research contributes to a emerging synthesis in origin-of-life science. No single environment or process appears responsible for life’s beginning. Instead, multiple environments contributed different pieces: hot vents provided energy and mineral catalysts, cold regions concentrated reactants and provided template surfaces, wet-dry cycles drove polymerization reactions. Life emerged from the intersection of these diverse processes.

This distributed model of origins has implications for the search for life elsewhere. If life required only one very specific environment, finding that environment would be necessary for life to exist. But if life emerged from a network of interconnected processes, many different planetary configurations might work. Any world with sufficient chemical diversity and energy flow might generate the conditions for life’s emergence, even if no single location matches Earth exactly.

The poison-to-life connection also illustrates a deeper principle. The difference between “poisonous” and “essential” is often a matter of context. Oxygen, necessary for human life, is actually toxic to many organisms and was a devastating pollutant when photosynthesis first released it into Earth’s atmosphere. What kills in one context may create in another.

Hydrogen cyanide, the infamous poison, may have been midwife to the first living cells. Frozen into crystals in a cold early Earth, it could have provided both the raw materials and the reaction templates needed to build the molecules of life. The chemistry of death and the chemistry of life are not so different. Both are just chemistry, operating in different contexts to produce vastly different outcomes.

Sources: ScienceDaily prebiotic chemistry research 2026, Journal of the American Chemical Society hydrogen cyanide ice studies, astrobiology origins of life reviews, NASA astrobiology program research.